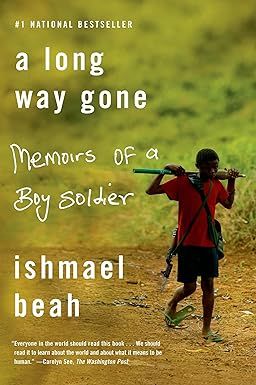

A Long Way Gone

4.6

-

7,450 ratings

This is how wars are fought now: by children, hopped-up on drugs and wielding AK-47s. Children have become soldiers of choice. In the more than fifty conflicts going on worldwide, it is estimated that there are some 300,000 child soldiers. Ishmael Beah used to be one of them.

What is war like through the eyes of a child soldier? How does one become a killer? How does one stop? Child soldiers have been profiled by journalists, and novelists have struggled to imagine their lives. But until now, there has not been a first-person account from someone who came through this hell and survived.

In A Long Way Gone, Beah, now twenty-five years old, tells a riveting story: how at the age of twelve, he fled attacking rebels and wandered a land rendered unrecognizable by violence. By thirteen, he'd been picked up by the government army, and Beah, at heart a gentle boy, found that he was capable of truly terrible acts. This is a rare and mesmerizing account, told with real literary force and heartbreaking honesty.

Kindle

$9.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$13.29

Paperback

$7.84

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

9780374531263

ISBN-13

978-0374531263

Print length

229 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Sarah Crichton Books

Publication date

May 08, 2008

Dimensions

5.5 x 0.75 x 8.5 inches

Item weight

7.5 ounces

Product details

ASIN :

0374531269

File size :

1260 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Editorial Reviews

“Everyone in the world should read this book. Not just because it contains an amazing story, or because it's our moral, bleeding-heart duty, or because it's clearly written. We should read it to learn about the world and about what it means to be human.” ―Washington Post

“A breathtaking and unselfpitying account of how a gentle spirit survives a childhood from which all innocence has suddenly been sucked out. It's a truly riveting memoir.” ―Time

“Beah is a gifted writer. . . Read his memoir and you will be haunted . . . It's a high price to pay, but it's worth it.” ―Newsweek.com

“Deeply moving, even uplifting…Beah's story, with its clear-eyed reporting and literate particularity--whether he's dancing to rap, eating a coconut or running toward the burning village where his family is trapped--demands to be read.” ―People (Critic's Choice, Four stars)

“Beah's memoir, A Long Way Gone (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), is unforgettable testimony that Africa's children--millions of them dying and orphaned by preventable diseases, hundreds of thousands of them forced into battle--have eyes to see and voices to tell what has happened. And what voices!” ―Melissa Fay Greene, Elle

“When Beah is finally approached about the possibility of serving as a spokesperson on the issue of child soldiers, he knows exactly what he wants to tell the world: "I would always tell people that I believe children have the resilience to outlive their sufferings, if given a chance. Others may make the same assertions, but Beah has the advantage of stating them in the first person. That makes A Long Way Gone all the more gripping.” ―Christian Science Monitor

“In place of a text that has every right to be a diatribe against Sierra Leone, globalization or even himself, Beah has produced a book of such self-effacing humanity that refugees, political fronts and even death squads resolve themselves back into the faces of mothers, fathers and siblings. A Long Way Gone transports us into the lives of thousands of children whose lives have been altered by war, and it does so with a genuine and disarmingly emotional force.” ―Minneapolis Star-Tribune

“What Beah saw and did during [the war] has haunted him ever since, and if you read his stunning and unflinching memoir, you'll be haunted, too . . . It would have been enough if Ishmael Beah had merely survived the horrors described in A Long Way Gone. That he has written this unforgettable firsthand account of his odyssey is harder still to grasp. Those seeking to understand the human consequences of war, its brutal and brutalizing costs, would be wise to reflect on Ishmael Beah's story.” ―Philadelphia Inquirer

“Beah speaks in a distinctive voice, and he tells an important story.” ―The Wall Street Journal

“Hideously effective in conveying the essential horror of his experiences.” ―Kirkus Reviews

“Extraordinary . . . A ferocious and desolate account of how ordinary children were turned into professional killers.” ―The Guardian UK

“A Long Way Gone is one of the most important war stories of our generation. The arming of children is among the greatest evils of the modern world, and yet we know so little about it because the children themselves are swallowed up by the very wars they are forced to wage. Ishmael Beah has not only emerged intact from this chaos, he has become one of its most eloquent chroniclers. We ignore his message at our peril.” ―Sebastian Junger, author of A Death in Belmont and A Perfect Storm

“This is a beautifully written book about a shocking war and the children who were forced to fight it. Ishmael Beah describes the unthinkable in calm, unforgettable language; his memoir is an important testament to the children elsewhere who continue to be conscripted into armies and militias.” ―Steve Coll, author of Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001, winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for general Nonfiction

“This is a wrenching, beautiful, and mesmerizing tale. Beah's amazing saga provides a haunting lesson about how gentle folks can be capable of great brutalities as well goodness and courage. It will leave you breathless.” ―Walter Isaacson, author of Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

“A Long Way Gone hits you hard in the gut with Sierra Leone's unimaginable brutality and then it touches your soul with unexpected acts of kindness. Ishmael Beah's story tears your heart to pieces and then forces you to put it back together again, because if Beah can emerge from such horror with his humanity in tact, it's the least you can do.” ―Jeannette Walls, author of The Glass Castle: A Memoir

Sample

Chapter One

There were all kinds of stories told about the war that made it sound as if it was happening in a faraway and different land. It wasn’t until refugees started passing through our town that we began to see that it was actually taking place in our country. Families who had walked hundreds of miles told how relatives had been killed and their houses burned. Some people felt sorry for them and offered them places to stay, but most of the refugees refused, because they said the war would eventually reach our town. The children of these families wouldn’t look at us, and they jumped at the sound of chopping wood or as stones landed on the tin roofs flung by children hunting birds with slingshots. The adults among these children from the war zones would be lost in their thoughts during conversations with the elders of my town. Apart from their fatigue and malnourishment, it was evident they had seen something that plagued their minds, something that we would refuse to accept if they told us all of it. At times I thought that some of the stories the passersby told were exaggerated. The only wars I knew of were those that I had read about in books or seen in movies such as Rambo: First Blood, and the one in neighboring Liberia that I had heard about on the BBC news. My imagination at ten years old didn’t have the capacity to grasp what had taken away the happiness of the refugees.

The first time that I was touched by war I was twelve. It was in January of 1993. I left home with Junior, my older brother, and our friend Talloi, both a year older than I, to go to the town of Mattru Jong, to participate in our friends’ talent show. Mohamed, my best friend, couldn’t come because he and his father were renovating their thatched-roof kitchen that day. The four of us had started a rap and dance group when I was eight. We were first introduced to rap music during one of our visits to Mobimbi, a quarter where the foreigners who worked for the same American company as my father lived. We often went to Mobimbi to swim in a pool and watch the huge color television and the white people who crowded the visitors’ recreational area. One evening a music video that consisted of a bunch of young black fellows talking really fast came on the television. The four of us sat there mesmerized by the song, trying to understand what the black fellows were saying. At the end of the video, some letters came up at the bottom of the screen. They read “Sugarhill Gang, ‘Rapper’s Delight.’” Junior quickly wrote it down on a piece of paper. After that, we came to the quarters every other weekend to study that kind of music on television. We didn’t know what it was called then, but I was impressed with the fact that the black fellows knew how to speak English really fast, and to the beat.

Later on, when Junior went to secondary school, he befriended some boys who taught him more about foreign music and dance. During holidays, he brought me cassettes and taught my friends and me how to dance to what we came to know as hip-hop. I loved the dance, and particularly enjoyed learning the lyrics, because they were poetic and it improved my vocabulary. One afternoon, Father came home while Junior, Mohamed, Talloi, and I were learning the verse of “I Know You Got Soul” by Eric B. & Rakim. He stood by the door of our clay brick and tin roof house laughing and then asked, “Can you even understand what you are saying?” He left before Junior could answer. He sat in a hammock under the shade of the mango, guava, and orange trees and tuned his radio to the BBC news.

“Now, this is good English, the kind that you should be listening to,” he shouted from the yard.

While Father listened to the news, Junior taught us how to move our feet to the beat. We alternately moved our right and then our left feet to the front and back, and simultaneously did the same with our arms, shaking our upper bodies and heads. “This move is called the running man,” Junior said. Afterward, we would practice miming the rap songs we had memorized. Before we parted to carry out our various evening chores of fetching water and cleaning lamps, we would say “Peace, son” or “I’m out,” phrases we had picked up from the rap lyrics. Outside, the evening music of birds and crickets would commence.

On the morning that we left for Mattru Jong, we loaded our backpacks with notebooks of lyrics we were working on and stuffed our pockets with cassettes of rap albums. In those days we wore baggy jeans, and underneath them we had soccer shorts and sweatpants for dancing. Under our long-sleeved shirts we had sleeveless undershirts, T-shirts, and soccer jerseys. We wore three pairs of socks that we pulled down and folded to make our crapes* look puffy. When it got too hot in the day, we took some of the clothes off and carried them on our shoulders. They were fashionable, and we had no idea that this unusual way of dressing was going to benefit us. Since we intended to return the next day, we didn’t say goodbye or tell anyone where we were going. We didn’t know that we were leaving home, never to return.

To save money, we decided to walk the sixteen miles to Mattru Jong. It was a beautiful summer day, the sun wasn’t too hot, and the walk didn’t feel long either, as we chatted about all kinds of things, mocked and chased each other. We carried slingshots that we used to stone birds and chase the monkeys that tried to cross the main dirt road. We stopped at several rivers to swim. At one river that had a bridge across it, we heard a passenger vehicle in the distance and decided to get out of the water and see if we could catch a free ride. I got out before Junior and Talloi, and ran across the bridge with their clothes. They thought they could catch up with me before the vehicle reached the bridge, but upon realizing that it was impossible, they started running back to the river, and just when they were in the middle of the bridge, the vehicle caught up to them. The girls in the truck laughed and the driver tapped his horn. It was funny, and for the rest of the trip they tried to get me back for what I had done, but they failed.

We arrived at Kabati, my grandmother’s village, around two in the afternoon. Mamie Kpana was the name that my grandmother was known by. She was tall and her perfectly long face complemented her beautiful cheekbones and big brown eyes. She always stood with her hands either on her hips or on her head. By looking at her, I could see where my mother had gotten her beautiful dark skin, extremely white teeth, and the translucent creases on her neck. My grandfather or kamor—teacher, as everyone called him—was a well-known local Arabic scholar and healer in the village and beyond.

At Kabati, we ate, rested a bit, and started the last six miles. Grandmother wanted us to spend the night, but we told her that we would be back the following day.

“How is that father of yours treating you these days?” she asked in a sweet voice that was laden with worry.

“Why are you going to Mattru Jong, if not for school? And why do you look so skinny?” she continued asking, but we evaded her questions. She followed us to the edge of the village and watched as we descended the hill, switching her walking stick to her left hand so that she could wave us off with her right hand, a sign of good luck.

We arrived in Mattru Jong a couple of hours later and met up with old friends, Gibrilla, Kaloko, and Khalilou. That night we went out to Bo Road, where street vendors sold food late into the night. We bought boiled groundnut and ate it as we conversed about what we were going to do the next day, made plans to see the space for the talent show and practice. We stayed in the verandah room of Khalilou’s house. The room was small and had a tiny bed, so the four of us (Gibrilla and Kaloko went back to their houses) slept in the same bed, lying across with our feet hanging. I was able to fold my feet in a little more since I was shorter and smaller than all the other boys.

The next day Junior, Talloi, and I stayed at Khalilou’s house and waited for our friends to return from school at around 2:00 p.m. But they came home early. I was cleaning my crapes and counting for Junior and Talloi, who were having a push-up competition. Gibrilla and Kaloko walked onto the verandah and joined the competition. Talloi, breathing hard and speaking slowly, asked why they were back. Gibrilla explained that the teachers had told them that the rebels had attacked Mogbwemo, our home. School had been canceled until further notice. We stopped what we were doing.

According to the teachers, the rebels had attacked the mining areas in the afternoon. The sudden outburst of gunfire had caused people to run for their lives in different directions. Fathers had come running from their workplaces, only to stand in front of their empty houses with no indication of where their families had gone. Mothers wept as they ran toward schools, rivers, and water taps to look for their children. Children ran home to look for parents who were wandering the streets in search of them. And as the gunfire intensified, people gave up looking for their loved ones and ran out of town.

“This town will be next, according to the teachers.” Gibrilla lifted himself from the cement floor. Junior, Talloi, and I took our backpacks and headed to the wharf with our friends. There, people were arriving from all over the mining area. Some we knew, but they couldn’t tell us the whereabouts of our families. They said the attack had been too sudden, too chaotic; that everyone had fled in different directions in total confusion.

For more than three hours, we stayed at the wharf, anxiously waiting and expecting either to see our families or to talk to someone who had seen them. But there was no news of them, and after a while we didn’t know any of the people who came across the river. The day seemed oddly normal. The sun peacefully sailed through the white clouds, birds sang from treetops, the trees danced to the quiet wind. I still couldn’t believe that the war had actually reached our home. It is impossible, I thought. When we left home the day before, there had been no indication the rebels were anywhere near.

“What are you going to do?” Gibrilla asked us. We were all quiet for a while, and then Talloi broke the silence. “We must go back and see if we can find our families before it is too late.”

Junior and I nodded in agreement.

Just three days earlier, I had seen my father walking slowly from work. His hard hat was under his arm and his long face was sweating from the hot afternoon sun. I was sitting on the verandah. I had not seen him for a while, as another stepmother had destroyed our relationship again. But that morning my father smiled at me as he came up the steps. He examined my face, and his lips were about to utter something, when my stepmother came out. He looked away, then at my stepmother, who pretended not to see me. They quietly went into the parlor. I held back my tears and left the verandah to meet with Junior at the junction where we waited for the lorry. We were on our way to see our mother in the next town about three miles away. When our father had paid for our school, we had seen her on weekends over the holidays when we were back home. Now that he refused to pay, we visited her every two or three days. That afternoon we met Mother at the market and walked with her as she purchased ingredients to cook for us. Her face was dull at first, but as soon as she hugged us, she brightened up. She told us that our little brother, Ibrahim, was at school and that we would go get him on our way from the market. She held our hands as we walked, and every so often she would turn around as if to see whether we were still with her.

As we walked to our little brother’s school, Mother turned to us and said, “I am sorry I do not have enough money to put you boys back in school at this point. I am working on it.” She paused and then asked, “How is your father these days?”

“He seems all right. I saw him this afternoon,” I replied. Junior didn’t say anything.

Mother looked him directly in the eyes and said, “Your father is a good man and he loves you very much. He just seems to attract the wrong stepmothers for you boys.”

When we got to the school, our little brother was in the yard playing soccer with his friends. He was eight and pretty good for his age. As soon as he saw us, he came running, throwing himself on us. He measured himself against me to see if he had gotten taller than me. Mother laughed. My little brother’s small round face glowed, and sweat formed around the creases he had on his neck, just like my mother’s. All four of us walked to Mother’s house. I held my little brother’s hand, and he told me about school and challenged me to a soccer game later in the evening. My mother was single and devoted herself to taking care of Ibrahim. She said he sometimes asked about our father. When Junior and I were away in school, she had taken Ibrahim to see him a few times, and each time she had cried when my father hugged Ibrahim, because they were both so happy to see each other. My mother seemed lost in her thoughts, smiling as she relived the moments.

Read more

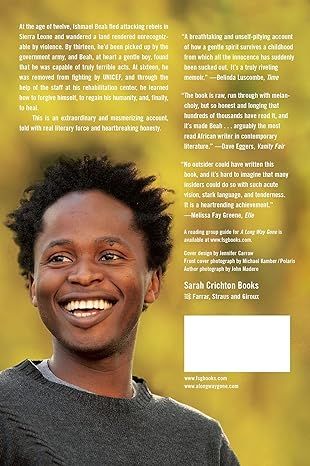

About the authors

Ishmael Beah

Ishmael Beah, born in Sierra Leone, West Africa, is the # 1 New York Times & international bestselling author of "A Long Way Gone, Memoirs of a Boy Soldier" & "Radiance of Tomorrow, A Novel." His books have been published in over 40 languages and won numerous prestigious awards and reviews. His Memoir was nominated for a Quill Award in the Best Debut Author category for 2007. Time Magazine named the book as one of the Top 10 Nonfiction books of 2007, ranking at number 3. Carolyn See from The Washington Post wrote, “Everyone in the world should read this book… We should read it to learn about the world and about what it means to be human.”

His novel, written with the gentle lyricism of a dream and the moral clarity of a fable is a powerful book about preserving what means the most to us, even in uncertain times.

The New York Times finds in his writing an "allegorical richness" and a "remarkable humanity to his characters". His forthcoming book "Little Family, A Novel" will be published in April 28, 2020 by Riverhead Books (Penguin USA).

He is a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador and advocate for Children by War, and a member of the Human Rights Watch Children Advisory Committed. He lives in Los Angeles, California with his wife and three children.

Read more

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.6 out of 5

7,450 global ratings

Jodee

5

Best book I’ve read all year long!!!

Reviewed in the United States on May 14, 2024

Verified Purchase

A Long Way Gone is inspiring but also a horrific memoir that talks about the author Ishmael Beah's experiences as a child soldier in his home land Sierra Leone. Because of his vivid and strong storytelling abilities, Ishmael takes us (his audience) on a journey through the horrors of war, end of his childhood, the loss of his innocence, and the ultimate redemptive power of hope and compassion, all while he is just a young boy. This powerful and unforgettable book is a true horror story of how a young boys spirit is able to endure even the most unimaginable circumstances possible

Read more

Kit

5

What a piece of work is man...

Reviewed in the United States on June 20, 2007

Verified Purchase

No matter how you slice it, Ishmael Beah is an amazing man.

This autobiographical account of his life details how a happy, cheerful young boy became a merciless soldier at the age of thirteen (and was not the oldest by far). How he went form living with his family in a small village in Sierra Leone to being a drug-addicted killer, ready to gun down anyone who got in the way. Not just killing people, but often doing so in especially brutal ways.

Most importantly it details his transformation back from the brink of seemingly endless death and violence into a college-educated young man and exceptional writer.

This is, without a doubt, one of the most harrowing, heartbreaking and moving stories I have ever read. Beautiful and honestly written. Passionate and personal, but also painting a larger picture of a world most of will, thank goodness, never experience.

For me personally the image that remains most stark is one of a neighbor of Ishmael's, a boy about his age, who is fleeing their village. The boy is carrying a sack of goods from his family's home. The only things he has left of his entire world. But it slows him down, then gets caught between a couple stumps. What happens to the boy is up to the reader to guess, but given that he was being shot at at the time, the likely conclusion is all too grim.

(rant approaching) Too often we Americans, comfortable in our relatively easy lives, are inclined to forget the rest of the world. If you asked the average person on the street to name five countries in Africa, they MIGHT get Egypt and South Africa, and then would probably wind up including Afghanistan. Our ignorance about the rest of the world in general and Africa in particular is inexcusible.

More than just about anything else this book convinces me that we, as a nation, need to do some sort of "Marshall Plan" for Africa. We can't go in with guns and bombs and make them like us. But we can go in with money, and schools, and medicine. Africa has all the resources it needs to be doing well. But they nevertheless continue to basically suck. Something must be done.

I highly recommend this book to readers 10 years or older. I especially recommend it to people who are in their early teens. Perhaps they can learn the horrible lessons Ishmael learned at their age without going through the traumas he experienced.

The one real criticism I have of the book is that, like "The Sopranos", it didn't END, so much as just STOP. One moment things are happening, you turn the page, and that's it. It's a minor complaint, but it's still there.

This is a book about horrible, horrible war, violence and despair. But it's also a book about hope. I started this review with a quote from Shakespeare, but I shall end with a quote from Cicero who once observed that, "While there's life, there's hope."

Read more

9 people found this helpful

rafael

5

A Long Way Gone Review

Reviewed in the United States on May 16, 2024

Verified Purchase

A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Beah is more than just a story, it's a real life account of surviving unimaginable hardships. Ishmael's experience as a child soldier in Sierra Leone makes his story credible and powerful, showing the true impact of war. His detailed descriptions of his struggles and emotional journey touched my heart, making me feel deep empathy and compassion. Ishmael's narrative reveals the harsh realities faced by many children in war zones. This book is essential for anyone who wants to understand the real cost of conflict and the incredible strength of hope and recovery.

Read more

Michelaneous by Michele

5

"Children have the resilience to outlive their sufferings . . .

Reviewed in the United States on February 7, 2008

Verified Purchase

. . . if given a chance."

Ishmael Beah, author of this remarkable and very disturbing memoir, is living proof of this statement. It was a statement initially prepared for him as a spokesperson on the issue of child soldiers during his rehabilitation period, and one he learned to repeat again and again, as he outlived not only this wartime sufferings, but also all of his family members and most of his friends.

"Why does everyone keep dying except me?" is a question that plagues him, and plagues the reader as well upon reading brutal account after brutal account of rebel attacks on otherwise peaceful villages in the West African country of Sierra Leone. It takes a strong stomach to read his gut-wrenching descriptions of the killings. But Beah is a gifted writer with a clear memory and the ability to relate vivid visual descriptions and express his feelings. This book gives new meaning to the phrase: "living to tell the tale."

For example: "Every time people come at us with the intention of killing us, I close my eyes and wait for death. Even though I am still alive, I feel like each time I accept death, part of me dies. Very soon I will completely die and all that will be left is my empty body walking with you. It will be quieter than I am." These were the words of a friend from a time before Beah and his group of teenage boys became drug-addicted, AK-47-carrying soldiers.

This is an important work about learning to understand not only the mind of a child soldier, but also the reasons behind how and why children become soldiers. Beah includes a chronology of events in Sierra Leone from 1462, when written history for the region began, until March, 2006. Very well written with a lot of rap and reggae music undertones, by a charming, educated, lucky, and grateful young man. Highly recommend.

Michele Cozzens, Author of A Line Between Friends and The Things I Wish I'd Said.

Read more

6 people found this helpful

voracious reader

4

Compelling

Reviewed in the United States on July 4, 2008

Verified Purchase

This is a compelling true story. A boy named Ishmael leaves his comfortable life in an African village to attend a rap music event with his brother and a few friends. While he is gone, rebel forces attack his village destroying his home and family life. He, his brother, Junior, and his friends then wander the countryside of Sierra Leone trying to survive and avoid both the rebel and government troops. Identifying the enemy is difficult in a country rich in resources and awash with government corruption. Ishmael is separated from his group and eventually attaches himself to another group of teenage boys all under 16. Eventually, the war catches up with him and he and his little band are conscripted into the government troops. For the next two or more years and armed with an AK 47 and RPG's, he kills, maims, and robs in the name of the government. These boy soldiers take many drugs to dull their feelings and allow themselves to participate in the inhumane slaughter. Finally, aid workers either buy the boys' freedom or settle with their army leader and obtain their release. They are taken into the custody of rehabilitation counselors where they are given an opportunity for redemption. Ishmael clearly a natural leader is selected to travel to New York to attend a U.N. conference on child soldiers. While there he makes many friends. I understand that he was taken in by one of them and that he subsequently attended Oberlin college.

I gave this book 4 stars instead of 5, because it drags a bit during the years of army participation and killing. Further, Ishmael's parents are divorced, but he lives with his father. His family is Muslim and that may be why the father retained custody. Very telling in the book was a description on pg. 77 (hardback) of his formal naming ceremony. A huge feast is prepared. First the elders eat their fill, then the men, then the boys and lastly the women and children. I presume that if there isn't enough to share, the women and children starve. I don't know if the author realized what he revealed about his culture by this telling description. However, we never learn the basis of the divorce or why his father retained custody. Living conditions were somewhat primative. The houses were made of concrete brick or mud and they had tin roofs which were particularly noisy when it rained. Their diet was complete though not luxurious, and they were not hungry. However, they walked for miles to save bus fare and did not have electricity or telephones in their homes. Sierra leone sounds like a terrible place. The film, Blood Diamond, was about a similar subject.

I really don't know if there is a solution when countrymen kill one another over money, resources, and power. However, perhaps, this book and the film, Blood diamond, will be the stimulus for a resolution.

This book was worth reading, and I recommend it.

Read more

4 people found this helpful

Best Sellers

The Great Alone: A Novel

4.6

-

152,447

$5.49

The Four Winds

4.6

-

156,242

$9.99

Winter Garden

4.6

-

72,838

$7.37

The Nightingale: A Novel

4.7

-

309,637

$8.61

Steve Jobs

4.7

-

24,596

$1.78

Iron Flame (The Empyrean, 2)

4.6

-

164,732

$14.99

A Court of Thorns and Roses Paperback Box Set (5 books) (A Court of Thorns and Roses, 9)

4.8

-

26,559

$37.99

Pretty Girls: A Novel

4.3

-

88,539

$3.67

The Bad Weather Friend

4.1

-

34,750

$12.78

Pucking Around: A Why Choose Hockey Romance (Jacksonville Rays Hockey)

4.3

-

41,599

$14.84

Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action

4.6

-

37,152

$9.99

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow: A novel

4.4

-

95,875

$13.99

Weyward: A Novel

4.4

-

27,652

$11.99

Tom Lake: A Reese's Book Club Pick

4.3

-

37,302

$15.74

All the Sinners Bleed: A Novel

4.4

-

12,894

$13.55

The Mystery Guest: A Maid Novel (Molly the Maid)

4.3

-

9,844

$14.99

Bright Young Women: A Novel

4.2

-

8,485

$14.99

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder (Random House Large Print)

4.5

-

28,672

$14.99

Hello Beautiful (Oprah's Book Club): A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.4

-

79,390

$14.99

Small Mercies: A Detective Mystery

4.5

-

16,923

$10.00

Holly

4.5

-

31,521

$14.99

The Covenant of Water (Oprah's Book Club)

4.6

-

69,712

$9.24

Wellness: A novel

4.1

-

3,708

$14.99

The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession

4.3

-

4,805

$14.99

The Berry Pickers: A Novel

4.5

-

14,209

$14.99

Elon Musk

4.7

-

15,272

$16.99

Just for the Summer

4.6

-

19,524

$11.99

Fourth Wing (International Edition)

4.8

-

206,495

$7.95

Remarkably Bright Creatures: A Read with Jenna Pick

4.6

-

65,556

$15.80

Tell Me Your Life Story, Mom: A Mother’s Guided Journal and Memory Keepsake Book (Tell Me Your Life Story® Series Books)

4.7

-

5,107

$11.24