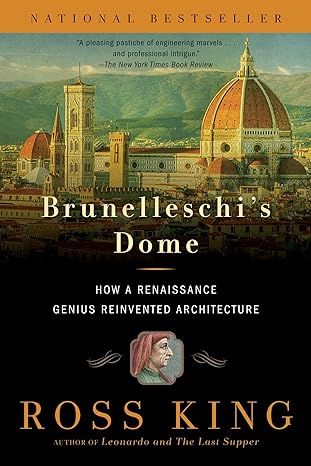

Brunelleschi's Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture

4.5

-

2,389 ratings

The New York Times bestselling, award winning story of the construction of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence and the Renaissance genius who reinvented architecture to build it.

On August 19, 1418, a competition concerning Florence's magnificent new cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore was announced: "Whoever desires to make any model or design for the vaulting of the main Dome....shall do so before the end of the month of September." The proposed dome was regarded far and wide as all but impossible to build: not only would it be enormous, but its original and sacrosanct design shunned the flying buttresses that supported cathedrals all over Europe. The dome would literally need to be erected over thin air.

Of the many plans submitted, one stood out--a daring and unorthodox solution to vaulting what is still the largest dome in the world. It was offered not by a master mason or carpenter, but by a goldsmith and clockmaker named Filippo Brunelleschi, then forty-one, who would dedicate the next twenty-eight years to solving the puzzles of the dome's construction. In the process, he reinvented the field of architecture.

Brunelleschi's Dome is the story of how a Renaissance genius bent men, materials, and the very forces of nature to build an architectural wonder we continue to marvel at today. Award-winning, bestselling author Ross King weaves this drama amid a background of the plagues, wars, political feuds, and the intellectual ferments of Renaissance Florence to bring the dome's creation to life in a fifteenth-century chronicle with twenty-first-century resonance.

Kindle

$3.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$32.94

Paperback

$12.29

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

1620401932

ISBN-13

978-1620401934

Print length

208 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Bloomsbury USA

Publication date

August 12, 2013

Dimensions

5.5 x 0.6 x 8.2 inches

Item weight

2.31 pounds

Product details

ASIN :

B00DUVKOUW

File size :

8854 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Sample

1

A More Beautiful

and Honourable Temple

On August 19, 1418, a competition was announced in Florence, where the city’s magnificent new cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore, had been under construction for more than a century:

Whoever desires to make any model or design for the vaulting of the main Dome of the Cathedral under construction by the Opera del Duomo—for armature, scaffold or other thing, or any lifting device pertaining to the construction and perfection of said cupola or vault—shall do so before the end of the month of September. If the model be used he shall be entitled to a payment of 200 gold Florins.

Two hundred florins was a good deal of money—more than a skilled craftsman could earn in two years of work—and so the competition attracted the attention of carpenters, masons, and cabinetmakers from all across Tuscany. They had six weeks to build their models, draw their designs, or simply make suggestions how the dome of the cathedral might be built. Their proposals were intended to solve a variety of problems, including how a temporary wooden support network could be constructed to hold the dome’s masonry in place, and how sandstone and marble blocks each weighing several tons might be raised to its top. The Opera del Duomo—the office of works in charge of the cathedral—reassured all prospective competitors that their efforts would receive “a friendly and trustworthy audience.”

Already at work on the building site, which sprawled through the heart of Florence, were scores of other craftsmen: carters, bricklayers, leadbeaters, even cooks and men whose job it was to sell wine to the workers on their lunch breaks. From the piazza surrounding the cathedral the men could be seen carting bags of sand and lime, or else clambering about on wooden scaffolds and wickerwork platforms that rose above the neighboring rooftops like a great, untidy bird’s nest. Nearby, a forge for repairing their tools belched clouds of black smoke into the sky, and from dawn to dusk the air rang with the blows of the blacksmith’s hammer and with the rumble of oxcarts and the shouting of orders.

Florence in the early 1400s still retained a rural aspect. Wheat fields, orchards, and vineyards could be found inside its walls, while flocks of sheep were driven bleating through the streets to the market near the Baptistery of San Giovanni. But the city also had a population of 50,000, roughly the same as London’s, and the new cathedral was intended to reflect its importance as a large and powerful mercantile city. Florence had become one of the most prosperous cities in Europe. Much of its wealth came from the wool industry started by the Umiliati monks soon after their arrival in the city in 1239. Bales of English wool—the finest in the world—were brought from monasteries in the Cotswolds to be washed in the river Arno, combed, spun into yarn, woven on wooden looms, then dyed beautiful colors: vermilion, made from cinnabar gathered on the shores of the Red Sea, or a brilliant yellow procured from the crocuses growing in meadows near the hilltop town of San Gimignano. The result was the most expensive and most sought-after cloth in Europe.

Because of this prosperity, Florence had undergone a building boom during the 1300s the like of which had not been seen in Italy since the time of the ancient Romans. Quarries of golden-brown sandstone were opened inside the city walls; sand from the river Arno, dredged and filtered after every flood, was used in the making of mortar, and gravel was harvested from the riverbed to fill in the walls of the dozens of new buildings that had begun springing up all over the city. These included churches, monasteries, and private palaces, as well as monumental structures such as a new ring of defensive walls to protect the city from invaders. Standing 20 feet high and running five miles in circumference, these fortifications, not finished until 1340, took more than fifty years to build. An imposing new town hall, the Palazzo Vecchio, had also been constructed, complete with a bell tower that stood more than 300 feet high. Another impressive tower was the cathedral’s 280-foot campanile, with its bas-reliefs and multicolored encrustations of marble. Designed by the painter Giotto, it had been completed in 1359, after more than two decades of work.

Yet by 1418 what was by far the grandest building project in Florence had still to be completed. A replacement for the ancient and dilapidated church of Santa Reparata, the new cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore was intended to be one of the largest in Christendom. Entire forests had been requisitioned to provide timber for it, and huge slabs of marble were being transported along the Arno on flotillas of boats. From the outset its construction had as much to do with civic pride as religious faith: the cathedral was to be built, the Commune of Florence had stipulated, with the greatest lavishness and magnificence possible, and once completed it was to be “a more beautiful and honourable temple than any in any other part of Tuscany.” But it was clear that the builders faced major obstacles, and the closer the cathedral came to completion, the more difficult their task would become.

Read more

About the authors

Ross King

Ross King is the author of the bestselling Brunelleschi's Dome and Michelangelo & the Pope's Ceiling, as well as the novels Ex-Libris and Domino. He lives in England, near Oxford.

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.5 out of 5

2,389 global ratings

Bruce Loveitt

5

Filippo's Dome Vs. Lorenzo's Doors

Reviewed in the United States on February 12, 2003

Verified Purchase

This is another great read from Mr. King. A week or two ago I finished his wonderful "Michelangelo And The Pope's Ceiling" and at that point decided I'd have to read "Brunelleschi's Dome". Over the past year or so I'd seen "Brunelleschi's Dome" in various bookstores and I'd skimmed through the pages- never buying it because I thought it looked too technical. I was put off by the various technical illustrations and thought, "Oh, this is really a book for an architect or engineer". But I was wrong. While there is no denying that the technical aspects are a major part of the book, the illustrations are very useful in helping the lay reader to understand the ingenious solutions that Brunelleschi came up with to overcome the numerous technical difficulties involved in the construction of such a large dome. By going into the nitty-gritty of the construction process, Mr. King allows us to appreciate Filippo's accomplishment. After all, this was a man who was a goldsmith and clockmaker- not an architect! And even though the book is under 200 pages in length, Mr. King manages to include a lot of interesting information other than the material which concerns the construction process. We learn about the lives of the masons who worked on the dome- how many days they worked (only about 200 per year, actually. They had off Sundays and religious feast days, which came about once a week. They also couldn't work in bad weather); what they ate and drank (surprisingly, although they were a couple of hundred feet above the ground they drank wine! Considering water quality at the time, wine was considered healthier. Florentines also believed that it "improved the blood, hastened digestion, calmed the intellect, enlivened the spirit, and expelled wind". Mr. King adds that wine "might also have given a fillip of courage to men clinging to an inward-curving vault..."!). Fillipo was very safety-conscious. Because of his precautions, only one man died during the 26 years Brunelleschi was in charge of the project. A good thing.....these were the days before workers' compensation and survivors' benefits! Another interesting theme of the book is the rivalry between Filippo and Lorenzo Ghiberti. Years earlier, Ghiberti had bested Brunelleschi in the contest to see who would be awarded the commission to cast and put up the bronze doors for the Baptistery of San Giovanni. Ghiberti won that competition. This time around Brunelleschi came up with the winning design. However, Ghiberti was still involved in "The Dome" project and there was no love lost between the two men. There was a lot of nasty backbiting behind the scenes of the "this guy doesn't know what the heck he's doing!" variety. Despite the fact that Ghiberti's baptistery doors are considered to be an artistic masterpiece (and were recognized as such even back then- even the persnickety Michelangelo marveled at the workmanship) the following anecdote will give you some idea of the ill-will between the two men: Lorenzo, who was generally an astute businessman and was always on the lookout for good places to put his money, had bought a farm in the hills above Florence. Mr. King writes, "As the farm, called Lepriano, did not prove a successful investment, Lorenzo was forced to sell it. Years later Filippo was asked what he thought was the best piece of work Lorenzo had ever done, to which he replied- "Selling Lepriano". If we add "comedian" to his long list of accomplishments, we see that Filippo Brunelleschi was indeed a true "Renaissance Man"!

Read more

19 people found this helpful

Amazon Customer

5

Interesting book

Reviewed in the United States on March 24, 2024

Verified Purchase

Good account of historic period

jboan

5

Fun to read

Reviewed in the United States on November 12, 2021

Verified Purchase

I have bought many books over the last couple of years and finished very few of them. This was one of the few I finished and I totally enjoyed reading it. I left work early once to get home to get back into the book and another time I turned off the volume watching a football game and picked up the book. Brunelleschi was the prototype for the Renaissance man. His dome is a masterpiece that inspired Michelangelo, who designed the dome of St. Peter's in Rome more than 100 years later. The dome of St. Paul' s in London and the U.S. Capitol in Washington were inspired by Brunelleschi's achievement. Leonardo da Vinci was inspired by Brunelleschi's inventions of machinery he used to hoist the huge stones into place. No scaffolding was used in the construction. No one knew if it could be done, since it had never been done before. The details of construction, the technical solutions he developed, and the political and economic obstructions he overcame, are interesting and well presented. The culture of Florence and the jealousies of competition with other artists, particularly Lorenzo Ghiberti, and the constant threats of wars and plagues provide the background. This book takes you there. I highly recommend it.

Read more

4 people found this helpful

Ricardo Mio

4

A Monument to Optimism

Reviewed in the United States on April 10, 2014

Verified Purchase

It was some contest. And some prize. The contest had come down to this: who among the achitects could stand an egg on its end. The prize was designing what would become the signature architectural landmark of Florence, Italy--the octagonal Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore. The year was 1418.

Such an undertaking would require more than mere artistic vision. It would require engineering techniques yet to be developed and something more: unshakeable optimism, for nothing like it had ever been done before. Indeed, few believed it could be done. The dome would have to begin at a height of 177 feet above the ground, span an opening of 138 feet, and rise to a height of 375 feet. To put it into perspective, the dome would rise from an opening 18 stories above the street, and top out at the equivalent of a 38-story building. Just getting building materials up to a height of an 18-story building to begin to begin the job would be a formidable undertaking in itself.

How the dome was built is the subject of "Brunelleschi's Dome" by Ross King. It's a fascinating story, and well told. Below are a few of the details.

Filippo Brunelleschi won the contest by challenging the other competing architects to make an egg stand on its end. After they all failed, he succeeded by pressing the blunt end down upon the table. When they answered that they could have done the same thing, he answered that they would make similar claims AFTER he had built his dome atop the cathedral. It was easy--when you knew how, and Brunelleschi knew how.

Brunelleschi's plan called for two domes--one within the other. The inner dome was built first and like the frame of an automobile contained a series of horizontal and vertical supports that held everything together. The horizontal supports consisted of a series of sandstone and wood beams and iron chains that circled the dome like the hoops of a barrel, to keep the structure from spreading outward. Being an octagon, there were vertical supports at each of the eight corners, curving inward toward the center, with two additional vertical supports between each corner support, for a total of 24 vertical supports. Couple with the circular horizontal supports, the entire structure was a lattice work of cross members embedded within the brick-and-mortar walls.

Center scaffolding is crucial in building arches and domes. Once center scaffolding is in place, rows of bricks are run up to the top of the scaffolding, and a keystone locks everything into place. Once the mortar sets, the scaffolding is taken down. Brunelleschi did not have this luxury, as there were not enough trees in all of Tuscany to build the necessary scaffolding to reach the heights that were presented. To get around it, he had the bricks laid in a herring-bone pattern that redirected the weight of the bricks against the vertical supports, instead of downward toward the ground. Once a row of bricks was locked into place and the cement had set, work proceeded on the next row, and continued like this, row upon row, upward and inward, the circle ever closing with each new row.

There were a multitude of other problems to be overcome. For one, workman became increasingly fearful as the dome rose ever higher and ever inward. With no visible means of support (and not understanding the law of compression), they believed the entire structure would collapse from its own weight and they would fall to their death. So they went on strike. When they finally returned (for less pay), a plague struck the city and work halted yet again. In all, it would take 16 years to build the dome.

Yet another problem was getting bricks and large stones up 18 stories to the base of the dome. To lift 37,000 metric tons of material, including over four million bricks, Brunelleschi invented hoisting machines that were widely copied by others including Leonardo de Vinci. The hoist not only raised material, it had a swinging arm for moving material laterally. The most revolutionary aspect was a reversible gear. The reversible gear allowed loads to ascend and descend without the need of turning around the oxen team each time the direction was changed.

Once the inner dome was completed, work proceeded on the outer dome. The outer dome carried the roof. Brunelleschi created a unique external covering system that consisted of tiles designed specially for easy assembly and maintenance. The vertical ribs seen at each of the dome's eight corners are not load-bearing and are more for aesthetics--to please the eye. Between the inner and outer domes is a cavity for stairs leading up to an observation platform at the summit of the dome. There are 463 steps that feel like 1000 when you reach the top. Making the climb and taking in the view is a must-do for visitors.

Brunelleschi designed the cupola at the top of dome, but did not live to see its completion. He did live to see the dome itself completed, one of the greatest achievements of Renaissance architecture. The dome has survived hurricane winds, and several earthquakes. In a city brimming with breathtaking art and architecture, the Dome of Florence is the city's most prized possession, and proof that one man with vision can do whatever he sets his mind on doing. However arresting to behold, the Dome of Florence is nothing less than a monument to optimism.

My one criticism of the book is with the illustrations. They are not well drawn, and in some cases not clear, such as the brick herringbone pattern used to build the dome: the illustration is small and difficult to figure out. I could figure it, without the illustration. Others may have trouble. For a book this well-researched and this well-written, this is inexcusable.

Read more

13 people found this helpful

K. Parsons

4

Slow start, resounding finish

Reviewed in the United States on December 19, 2002

Verified Purchase

It took me several months to really get into this book. Usually I know right away whether a book will grip my imagination and draw me in. "Brunelleschi's Dome" did, however, turn out to be one of the true literary surprises of the year for me. I wrote a term paper about Brunelleschi and the Florence Cathedral waaay back in high school for a technical drafting class. It was that experience, many years ago, that led me to buy the book. Now an architect in private practice, I have the technical and artistic background to appreciate what then was bewildering and rather foreign to me. This book very slowly grew on me, until one evening I couldn't put it down. Once the initial history, setup and definitions were safely read and out of the way, this book really got interesting in a hurry. The portrayal of the unintentional designer who, 500 years later, has come to be one of the recognized geniuses of the Renaissance and a founding father of Western architectural thought is fascinating, surprising and at times downright strange. Brunelleschi's time half a millenium ago is brought to life vividly. The technical descriptions of what are still today considered amazing breakthroughs are well written, informative and enlightening without being unwieldy, self indulgent or too long. This alone is a skill many architectural writers are abysmally deficient in, preferring to fill pages with their own blather and pseudo-language ostensibly designed to make the "rest of us" hold them in awe. Ross King's departure from the language of architecture's current flirtation with trendy academia is refreshing, readable and understandable by those not in the professions of architecture, engineering or building. It is revealing that my 14 year old cousin, a young man with sharp interests in astronomy and rock music, enjoyed this book immensely.

Read more

17 people found this helpful

Best Sellers

The Great Alone: A Novel

4.6

-

152,447

$5.49

The Four Winds

4.6

-

156,242

$9.99

Winter Garden

4.6

-

72,838

$7.37

The Nightingale: A Novel

4.7

-

309,637

$8.61

Steve Jobs

4.7

-

24,596

$1.78

Iron Flame (The Empyrean, 2)

4.6

-

164,732

$14.99

A Court of Thorns and Roses Paperback Box Set (5 books) (A Court of Thorns and Roses, 9)

4.8

-

26,559

$37.99

Pretty Girls: A Novel

4.3

-

88,539

$3.67

The Bad Weather Friend

4.1

-

34,750

$12.78

Pucking Around: A Why Choose Hockey Romance (Jacksonville Rays Hockey)

4.3

-

41,599

$14.84

Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action

4.6

-

37,152

$9.99

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow: A novel

4.4

-

95,875

$13.99

Weyward: A Novel

4.4

-

27,652

$11.99

Tom Lake: A Reese's Book Club Pick

4.3

-

37,302

$15.74

All the Sinners Bleed: A Novel

4.4

-

12,894

$13.55

The Mystery Guest: A Maid Novel (Molly the Maid)

4.3

-

9,844

$14.99

Bright Young Women: A Novel

4.2

-

8,485

$14.99

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder (Random House Large Print)

4.5

-

28,672

$14.99

Hello Beautiful (Oprah's Book Club): A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.4

-

79,390

$14.99

Small Mercies: A Detective Mystery

4.5

-

16,923

$10.00

Holly

4.5

-

31,521

$14.99

The Covenant of Water (Oprah's Book Club)

4.6

-

69,712

$9.24

Wellness: A novel

4.1

-

3,708

$14.99

The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession

4.3

-

4,805

$14.99