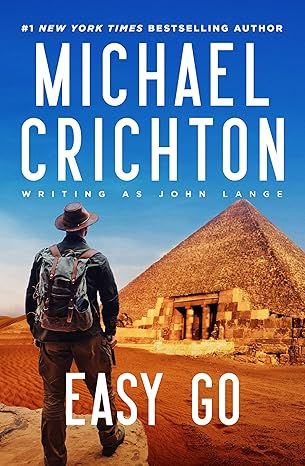

Easy Go

4.2

-

3,131 ratings

From the creator of Jurassic Park and ER

Egyptologist Harold Barnaby has just made the discovery of the century. While retranslating some old hieroglyphs, he has found clues to the location of a pharaoh's lost tomb. But this discovery leads him to make the ultimate choice: rather than share his find with the rest of the world, Professor Barnaby is determined to locate the tomb and keep whatever treasure he finds inside for himself.

But to pull off the greatest heist in the archaeological history, Barnaby will need help. Enter Robert Pierce, a transient freelance writer looking for excitement. They put together a five-man team, including a smuggler, an international thief, and the fifth Earl of Wheatston to bankroll the project, and set out to plunder the pharaoh's lost tomb. But can this ragtag team survive the perils of the Egyptian desert and uncover what the centuries have kept hidden? And even if they find the treasure, can they escape with it alive?

With a new introduction by Sherri Crichton

Kindle

$1.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$16.91

Paperback

$17.99

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

820098710H

ISBN-13

979-8200987108

Print length

344 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Blackstone Publishing, Inc.

Publication date

January 06, 2025

Dimensions

9 x 6 x 2 inches

Item weight

4 pounds

Product details

ASIN :

B0CZSCKGX4

File size :

3055 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Editorial reviews

"I look forward to dipping into all the early Crichton reissues, which are highly intriguing and made all the more special by the typical care with which Hard Case and Titan have handled them." - ChiZine

"This is a great adventure book, with plenty of colorful characters, but most importantly to me, it really shows how GOOD pulp should be." - Trash Mutant

“Many stunning women are inserted throughout the story for interesting flavor. I would definitely recommend this Hard Case Crime novel to any reader who has a vivid imagination and a long, free afternoon to decipher and guess plot twists along the way.” – Night Owl Reviews

"Great delight to Crichton fans who are still mourning his 2008 passing." Geek Girl Project

Sample

“Everything forbidden is sweet” —arab proverb

ONE

BARNABY

The Great Pyramid of Cheops filled the horizon. It was titanic, a giant mass of yellow-brown stone stretching wide and high, staggering the imagination. Harold Barnaby stood near the base, in the vast shadow of the pyramid, talking to a guide. “I want to go up,” he said.

The dragoman looked at him wearily, then shrugged. “Okay, boss,” he said. “I show you.”

“Good.”

Barnaby looked up the facade to the top. From a distance, the pyramid appeared to slope gently; up close, it seemed almost sheer. A group of tourists were coming down. They were small specks, barely visible from where he stood.

“You are alone?” the dragoman asked. He was a short fellow, very dark, wearing baggy trousers, sandals, and—incongruously—a black suit coat, on which was pinned his brass license.

“Yes,” Barnaby said. “I’m alone.”

“Okay, boss. We go now. You do what I do, okay? Feet like mine, hands like mine. I show you.” He started off, Barnaby following closely. Barnaby would have preferred to climb by himself, but the police required a guide. Now, as they began the ascent, he understood why. The blocks were immense, three or four feet high and sometimes six feet long. In many places, there was no more than a foot of ledge between tiers, and the path had been worn treacherously smooth by the tread of countless tourists before him.

Climbing was hard work; the guide set a quick pace. He seemed adept at scrambling over the four-foot stones, but Barnaby was cautious. The ground was very far away. Taxis and camels were minuscule. As they climbed the southeast edge, he soon found that he could see all of Cairo, fifteen miles away. Though it had been stifling hot on the ground, the wind blew strongly up here, tugging at his clothes.

The guide stopped to wait for him.

Barnaby was moving carefully now, for his hands were covered with fine dry sand, and he did not trust his grip. He heaved himself up, over block after block, until he reached the guide.

“Okay, boss?”

“Sure,” Barnaby said, winded. They were standing halfway up, with the desert and the Nile and Cairo spread out before them. He could not see the other pyramids of Giza or the Sphinx—the Great Pyramid blocked their view.

“Pretty, yes?”

Barnaby nodded. He very carefully did not look down. He was painfully aware that they were both standing on a narrow ledge not wider than two feet.

“Let’s go on.”

“Okay, boss.”

They climbed.

Now it began in earnest: the wind whistled in his ears and blew sand in his eyes. He noticed the names of tourists cut into the huge stones; he forced his mind to read them, trying to forget the height. The way was steeper still, and once the guide had to stop to find the path again. Barnaby found he was sweating.

He cursed himself for wanting to do this, and paused to wipe his hands on his pants—one hand at a time, always holding onto the rock. And yet he knew that he had to climb the Great Pyramid. He would never forgive himself if he came to Egypt and did not try it.

Quite suddenly, they reached the top. Barnaby, who had resigned himself to climbing forever, was startled to see a flat space some ten feet square. The guide bent over and helped him over the final block.

He stood on top of the pyramid of Cheops, or Khufu. He felt his legs shake from relief and excitement and sat down quickly to admire the view. From his vantage point, all Cairo lay spread out at the head of the green Nile Delta. He could see the radio tower, the mosques, and the citadel. To the south, on this side of the river, were the scattered pyramid fields of Saqqara and Dashur. And behind him—he turned to see them—were the two small pyramids of Giza, the burial chambers of Khafre and Menkure.

He recalled standing atop the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacán, outside Mexico City, and looking across at the smaller Pyramid of the Moon. It was a similar feeling, but this was different. Egypt imbued the view with a heavy sense of mystery and foreboding. He reached into his pocket for a cigarette, turning his thoughts to his problem.

** --------**

For the first time in his life, Harold Barnaby, 41, associate professor of archaeology at the University of Chicago, was contemplating dishonesty on a grand scale.

Barnaby was an Egyptologist, and his particular interest was hieroglyphics. He was an astute linguist, a talent that had been evident from childhood. His interest in language, in obscure writings, and difficult grammars had led him in college to study the languages of the Near East—languages both living and dead. It had been the purest chance, the taunt of a fellow graduate student, that had started him on Egyptian hieroglyphics. Now he could read the characters almost as rapidly as he read English.

While a student, he had become fascinated with all aspects of Egyptian life as revealed by the writing.

And slowly, he had come to understand that much that had been translated was wrong.

It was this knowledge that had first brought Barnaby to Cairo, six weeks earlier. He had a grant to study previously translated papyri, for it was his contention that such a study would radically change all existing notions of life in the dynasties of the Middle Kingdom—an era of Egyptian history characterized by the spread of empire, fabulous wealth, and vast armies.

The day after his arrival in Cairo, he had met the proper people—the curator of the Egyptian Museum, the director of the Antiquities Service of the United Arab Republic—and had been established in a little room in an obscure corner of the rambling building. The room was bare, consisting only of a table, a chair, and a lethargic guard. One after another, the precious papyri were brought to him, and he checked the manuscripts against the translated texts. He read of the military engagements of Thutmose III, seventeen times conqueror of the Hyksos; of the court machinations of Hatshepsut; of the glories of Ikhnaton. He reviewed, like an auditor, the messages, dispatches, and bills of pharaohs dead 3,000 years. A whole new world came to his eyes as he read—he forgot the guard and his foul-smelling cigarettes, forgot the heat and dust that streamed in through the open window, forgot the clanking noise of Cairo outside.

He was completely immersed and completely happy. Until two days ago.

Barnaby had been reading a document recovered from one of the Tombs of the Nobles, the rock-cut chambers in the cliffs of Thebes, Deir el-Medinet, across the river from modern Luxor. It was the tomb of a court majordomo, a vizier named Butehi, who had served one of the many kings who succeeded Tutankhamen in rapid succession—just which king was uncertain; the history of the period was confused.

This particular papyrus had been originally translated as pertaining to the procurement of firewood for the queen’s hot baths and the disposition of slaves to attend her majesty. Now, rereading it. Barnaby was disturbed. It had been translated from right to left, which made some sense, but very little; the original translator had squeezed the grammar into his own conception of the meaning.

Translating from left to right was not much improvement. He tried reading the hieroglyphics vertically, top to bottom (the Egyptians wrote all three ways), but still no success. It was frustrating.

He began to wonder about this innocuous little passage. He was about to put it aside as not worth the effort when he had a flash of intuition, the result of long years of translating such manuscripts. He suddenly, instinctively, sensed it was important. He looked at it again and tried working from bottom to top. Still nothing.

There were no cartouches in this particular passage. That was odd. Also, the spacing of the hieroglyphs was irregular, the arrangement suggesting some kind of trick. Was it a code? If so, he was lost—it would take as long to break it as it had taken Champollion to discover the clue to deciphering the hieroglyphics in the first place.

He played with the message, rearranging the symbols, testing simple replacements. He got nowhere. He sat back, lit a cigarette, and thought about the character of the man who had caused this passage to be written. What could have been so important that it required a departure from normal writing patterns?

This man, this vizier, would no doubt have access to many secrets of the pharaoh be served. He would also be vain, as was Rekhmire, who was the vizier of Thutmose III. Rekhmire had said of himself that there was nothing he did not know, in heaven, in earth, or any quarter of the underworld; he had inscribed that on his own tomb. But the viziers were important—in their own times, they were the second most powerful men in the world.

Yes, he would be vain. And he would wish to inscribe on his tomb the deeds he had accomplished, the successful administrative acts he had managed.

Staring at the papyrus, Barnaby finished his cigarette and still had no answer. He stubbed out the butt and pushed aside the ashtray. When he looked back at the rows of symbols, he suddenly saw it, clear as day.

Diagonals.

The passage was to be read diagonally. That was what the spacing hinted at. He tried, from top left to bottom right, and got nothing. Then he tried top right to bottom left and found that it read,

My majesty, lord of east and west, over all things ruler, commanded

He worked on the next diagonal, but it did not follow directly. It said something about a dwelling-place eternal, but he could not get the syntax correctly. Perhaps it was necessary to skip a diagonal and then come back.

Barnaby studied the manuscript for two hours. He found that there was no regular arrangement in the order of lines, but that the whole could be fitted together to make a reasonable statement.

My majesty, lord of east and west, over all things ruler, commanded, and I have made for him a place that may be satisfying to him therewith, forever and ever. I have built [my] majesty, my father, a rest for the heavens, a dwelling-place eternal, which no one knows and which not shall be found. My architect, my son-in-law, shall be nameless as the dwelling-place, known to no [man].

Barnaby glanced over at the guard in the corner, who was half-asleep, chair pushed back against the wall. A fly buzzed aimlessly around the room.

In deep the rock, a work of fifty men, is located the place, final rest, of [my] majesty, lord of east and west, ruler of the peoples. Not where many kings have been disturbed, but near; not so low, but high; in the north, where only by this may it be known. From the arcade of the woman-king, halfway, and north 6 iter, 1 khet, to the high cleft where fly the birds, for they draw near to [heaven] even as my majesty, in eternal rest. The fifty slaves lie near the dwelling-place, and my son-in-law watches over them. I have done this myself, and only I know the place. It was a great work that I did there, and my wisdom shall draw praise for ages after.

It was incredible. Barnaby read it again, and still again. He could not believe what he saw, though it was beyond doubt. This was the record of an official who had made the tomb of an unnamed 19th-Dynasty pharaoh and who had personally murdered all those who had worked on the tomb, including his own son-in-law. And yet, the man could not restrain from recording the deed for posterity in his own tomb. It was, Barnaby thought, typically Egyptian—kill fifty people to guard the secret, but announce it blandly for all to see on your own tomb.

But was it so bland?

He looked again at the original translation. Read right to left, the passage did make some sense. Perhaps that was why the vizier had felt secure—he had hidden his secret within another statement that could be interpreted as a commonplace record. It was clever.

Barnaby stood up and walked to the window. The guard stirred, looked at him, and relaxed again. Barnaby stared out at the city, turning yellow-red in the afternoon light. A streetcar rumbled past, crammed with passengers, bearing an advertisement for Aswan Beer.

It was a staggering opportunity, he realized. With this information, he had a reasonable chance of finding the tomb—and there was a reasonable chance that it would still be intact. Most tombs of the 18th–20th dynasties had been robbed, usually a few years after the pharaoh’s death. But if the preparations had been conducted in such ruthless secrecy, and if the official was as cunning in all things as he had been in the manner of telling the secret, then there was a chance. Harold Barnaby could become famous overnight, the discoverer of a tomb to rival Tutankhamen’s. He could have a full professorship in archaeology at any university in the world. His name would become a household word, as common as King Tut’s was now.

There would be secret passages, of course, and dead ends, and a great deal of hard, dusty work, but if he were successful . . .

Professor Barnaby. He tried the name on his tongue, silently. Professor Barnaby, the first man to break the seals on the door and enter the underground sepulcher, the first man to see the sarcophagus and the fabulous treasure stored with it. The first man in 3,000 years to gaze at all this, as the flashbulbs popped and the newsreel cameras whirred.

He smiled, and then his eyes narrowed, and he frowned. Something had occurred to him, something tempting and horrifying. At that moment, staring out of the window of the Egyptian Museum, the conflict was established—a conflict that was still not resolved.

Read more

About the authors

John Lange

John Lange is a pseudonym of author Michael Crichton. His pen name was selected as reference to his above-average height of 6' 9"(2.06 meters). Lange means "tall one" in German, Danish and Dutch.

Librarian's note: There is more than one author in the Goodreads database with this name.

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.2 out of 5

3,131 global ratings

Granny Jannie

5

Excellent story

Reviewed in the United States on April 27, 2024

Verified Purchase

One of Crichton us best. Great character and plot development in true Crichton style. Lots of action and plot twists. I loved the ending. Its hard to imagine he had time and energy to produce his masterpieces while also attending Harvard medical school. I'm so sorry he's gone, but happy he left us his creativity. Well done, and RIP, Michael. Well done!

Read more

2 people found this helpful

John Carroll

5

Adventure and exploration

Reviewed in the United States on December 31, 2023

Verified Purchase

A very interesting story with an unexpected conclusion. The characters had diverse backgrounds but came together for a joint project, while this was a work of fiction there were many interesting facts about Egypt and the surrounding Region. A great read.

Resa Rivers

5

Crichton never disappoints

Reviewed in the United States on January 29, 2024

Verified Purchase

A master or suspense and twist on the6 plot. An archeologist, a journalist team up with a very rich Lord to look for a tomb of a Egyptian king not known till now. Great read.

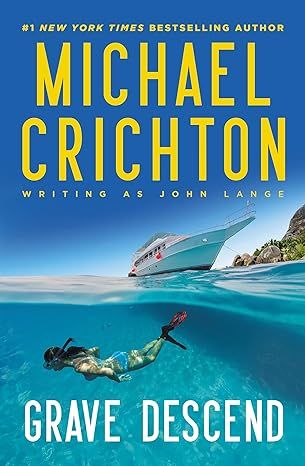

Top John Lange titles

View allSimilar Books

Best sellers

View all

The Tuscan Child

4.2

-

100,022

$8.39

The Thursday Murder Club: A Novel (A Thursday Murder Club Mystery)

4.3

-

155,575

$6.33

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

4.6

-

140,302

$13.49

The Butterfly Garden (The Collector, 1)

4.3

-

88,556

$9.59

Things We Hide from the Light (Knockemout Series, 2)

4.4

-

94,890

$11.66

The Last Thing He Told Me: A Novel

4.3

-

154,085

$2.99

The Perfect Marriage: A Completely Gripping Psychological Suspense

4.3

-

143,196

$9.47

The Coworker

4.1

-

80,003

$13.48

First Lie Wins: A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.3

-

54,062

$14.99

Mile High (Windy City Series Book 1)

4.4

-

59,745

$16.19

Layla

4.2

-

107,613

$8.99

The Locked Door

4.4

-

94,673

$8.53