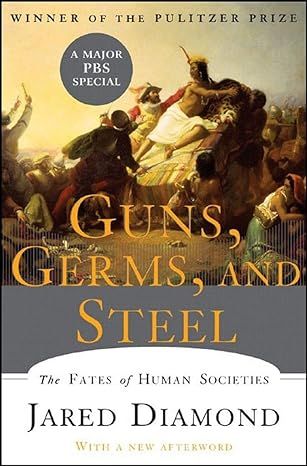

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies

4.5

-

13,373 ratings

"Fascinating.... Lays a foundation for understanding human history."―Bill Gates

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Guns, Germs, and Steel is a brilliant work answering the question of why the peoples of certain continents succeeded in invading other continents and conquering or displacing their peoples. This edition includes a new chapter on Japan and all-new illustrations drawn from the television series. Until around 11,000 BC, all peoples were still Stone Age hunter/gatherers. At that point, a great divide occurred in the rates that human societies evolved. In Eurasia, parts of the Americas, and Africa, farming became the prevailing mode of existence when indigenous wild plants and animals were domesticated by prehistoric planters and herders. As Jared Diamond vividly reveals, the very people who gained a head start in producing food would collide with preliterate cultures, shaping the modern world through conquest, displacement, and genocide.The paths that lead from scattered centers of food to broad bands of settlement had a great deal to do with climate and geography. But how did differences in societies arise? Why weren't native Australians, Americans, or Africans the ones to colonize Europe? Diamond dismantles pernicious racial theories tracing societal differences to biological differences. He assembles convincing evidence linking germs to domestication of animals, germs that Eurasians then spread in epidemic proportions in their voyages of discovery. In its sweep, Guns, Germs and Steel encompasses the rise of agriculture, technology, writing, government, and religion, providing a unifying theory of human history as intriguing as the histories of dinosaurs and glaciers.

Diamond argues that Eurasian civilization is not so much a product of ingenuity, but of opportunity and necessity. That is, civilization is not created out of superior intelligence, but is the result of a chain of developments, each made possible by certain preconditions.

The first step towards civilization is the move from nomadic hunter-gatherer to rooted agrarian society. Several conditions are necessary for this transition to occur: access to high-carbohydrate vegetation that endures storage; a climate dry enough to allow storage; and access to animals docile enough for domestication and versatile enough to survive captivity. Control of crops and livestock leads to food surpluses. Surpluses free people to specialize in activities other than sustenance and support population growth. The combination of specialization and population growth leads to the accumulation of social and technological innovations which build on each other. Large societies develop ruling classes and supporting bureaucracies, which in turn lead to the organization of nation-states and empires.

Although agriculture arose in several parts of the world, Eurasia gained an early advantage due to the greater availability of suitable plant and animal species for domestication. In particular, Eurasia has barley, two varieties of wheat, and three protein-rich pulses for food; flax for textiles; and goats, sheep, and cattle. Eurasian grains were richer in protein, easier to sow, and easier to store than American maize or tropical bananas.

Kindle

$9.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$24.80

Paperback

$14.95

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

0393317552

ISBN-13

978-0393061314

Print length

528 pages

Language

English

Publisher

W. W. Norton & Company

Publication date

July 16, 2005

Dimensions

6.4 x 1.6 x 9.6 inches

Item weight

2.03 pounds

Popular Highlights in this book

History followed different courses for different peoples because of differences among peoples’ environments, not because of biological differences among peoples themselves.

Highlighted by 5,253 Kindle readers

Those extinctions eliminated all the large wild animals that might otherwise have been candidates for domestication, and left native Australians and New Guineans with not a single native domestic animal.

Highlighted by 3,059 Kindle readers

Why did wealth and power become distributed as they now are, rather than in some other way?

Highlighted by 2,962 Kindle readers

Human history at last took off around 50,000 years ago, at the time of what I have termed our Great Leap Forward.

Highlighted by 2,832 Kindle readers

Product details

ASIN :

0393061310

File size :

115869 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Not Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Award Winners:

Editorial Reviews

"Artful, informative, and delightful.... There is nothing like a radically new angle of vision for bringing out unsuspected dimensions of a subject, and that is what Jared Diamond has done." ― William H. McNeil, New York Review of Books

"An ambitious, highly important book." ― James Shreeve, New York Times Book Review

"A book of remarkable scope, a history of the world in less than 500 pages which succeeds admirably, where so many others have failed, in analyzing some of the basic workings of culture process.... One of the most important and readable works on the human past published in recent years." ― Colin Renfrew, Nature

"The scope and the explanatory power of this book are astounding." ― The New Yorker

"No scientist brings more experience from the laboratory and field, none thinks more deeply about social issues or addresses them with greater clarity, than Jared Diamond as illustrated by Guns, Germs, and Steel. In this remarkably readable book he shows how history and biology can enrich one another to produce a deeper understanding of the human condition." ― Edward O. Wilson, Pellegrino University Professor, Harvard University

"Serious, groundbreaking biological studies of human history only seem to come along once every generation or so. . . . Now [Guns, Germs, and Steel] must be added to their select number. . . . Diamond meshes technological mastery with historical sweep, anecdotal delight with broad conceptual vision, and command of sources with creative leaps. No finer work of its kind has been published this year, or for many past." ― Martin Sieff, Washington Times

"[Diamond] is broadly erudite, writes in a style that pleasantly expresses scientific concepts in vernacular American English, and deals almost exclusively in questions that should interest everyone concerned about how humanity has developed. . . . [He] has done us all a great favor by supplying a rock-solid alternative to the racist answer. . . . A wonderfully interesting book." ― Alfred W. Crosby, Los Angeles Times

"An epochal work. Diamond has written a summary of human history that can be accounted, for the time being, as Darwinian in its authority." ― Thomas M. Disch, The New Leader

Sample

WHY IS WORLD HISTORY LIKE AN ONION?

THIS BOOK ATTEMPTS TO PROVIDE A SHORT HISTORY OF everybody for the last 13,000 years. The question motivating the book is: Why did history unfold differently on different continents? In case this question immediately makes you shudder at the thought that you are about to read a racist treatise, you aren’t: as you will see, the answers to the question don’t involve human racial differences at all. The book’s emphasis is on the search for ultimate explanations, and on pushing back the chain of historical causation as far as possible.

Most books that set out to recount world history concentrate on histories of literate Eurasian and North African societies. Native societies of other parts of the world—sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas, Island Southeast Asia, Australia, New Guinea, the Pacific Islands—receive only brief treatment, mainly as concerns what happened to them very late in their history, after they were discovered and subjugated by western Europeans. Even within Eurasia, much more space gets devoted to the history of western Eurasia than of China, India, Japan, tropical Southeast Asia, and other eastern Eurasian societies. History before the emergence of writing around 3,000 B.C. also receives brief treatment, although it constitutes 99.9% of the five-million-year history of the human species.

Such narrowly focused accounts of world history suffer from three disadvantages. First, increasing numbers of people today are, quite understandably, interested in other societies besides those of western Eurasia. After all, those “other” societies encompass most of the world’s population and the vast majority of the world’s ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groups. Some of them already are, and others are becoming, among the world’s most powerful economies and political forces.

Second, even for people specifically interested in the shaping of the modern world, a history limited to developments since the emergence of writing cannot provide deep understanding. It is not the case that societies on the different continents were comparable to each other until 3,000 B.C., whereupon western Eurasian societies suddenly developed writing and began for the first time to pull ahead in other respects as well. Instead, already by 3,000 B.C., there were Eurasian and North African societies not only with incipient writing but also with centralized state governments, cities, widespread use of metal tools and weapons, use of domesticated animals for transport and traction and mechanical power, and reliance on agriculture and domestic animals for food. Throughout most or all parts of other continents, none of those things existed at that time; some but not all of them emerged later in parts of the Native Americas and sub-Saharan Africa, but only over the course of the next five millennia; and none of them emerged in Aboriginal Australia. That should already warn us that the roots of western Eurasian dominance in the modern world lie in the preliterate past before 3,000 B.C. (By western Eurasian dominance, I mean the dominance of western Eurasian societies themselves and of the societies that they spawned on other continents.)

Third, a history focused on western Eurasian societies completely bypasses the obvious big question. Why were those societies the ones that became disproportionately powerful and innovative? The usual answers to that question invoke proximate forces, such as the rise of capitalism, mercantilism, scientific inquiry, technology, and nasty germs that killed peoples of other continents when they came into contact with western Eurasians. But why did all those ingredients of conquest arise in western Eurasia, and arise elsewhere only to a lesser degree or not at all?

All those ingredients are just proximate factors, not ultimate explanations. Why didn’t capitalism flourish in Native Mexico, mercantilism in sub-Saharan Africa, scientific inquiry in China, advanced technology in Native North America, and nasty germs in Aboriginal Australia? If one responds by invoking idiosyncratic cultural factors—e.g., scientific inquiry supposedly stifled in China by Confucianism but stimulated in western Eurasia by Greek or Judaeo-Christian traditions—then one is continuing to ignore the need for ultimate explanations: why didn’t traditions like Confucianism and the Judaeo-Christian ethic instead develop in western Eurasia and China, respectively? In addition, one is ignoring the fact that Confucian China was technologically more advanced than western Eurasia until about A.D. 1400.

It is impossible to understand even just western Eurasian societies themselves, if one focuses on them. The interesting questions concern the distinctions between them and other societies. Answering those questions requires us to understand all those other societies as well, so that western Eurasian societies can be fitted into the broader context.

Read more

About the authors

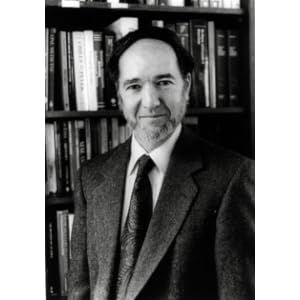

Jared Diamond

Jared Diamond is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Guns, Germs, and Steel, which was named one of TIME’s best non-fiction books of all time, the number one international bestseller Collapse and most recently The World Until Yesterday. A professor of geography at UCLA and noted polymath, Diamond’s work has been influential in the fields of anthropology, biology, ornithology, ecology and history, among others.

Read more

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.5 out of 5

13,373 global ratings

Tim F. Martin

5

Outstanding work of history, one of the best ever

Reviewed in the United States on April 15, 2005

Verified Purchase

Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond is one of the most informative, epic, well-written, and fascinating "macrohistory" books I have ever read. In this book, Diamond discussed the rise of complex human societies in the last 13,000 years, seeking to answer one fundamental question; why did some civilizations come to dominate others? Why did the Fertile Crescent and China for instance develop advanced societies with, as the title suggests, guns, germs, and steel, while other areas of the world, such as Polynesia, Australia, and the Americas, did not? Or in those cases where some civilizations were beginning to acquire such things, why did they get off to such a late start? Why did the Spanish conquer the Incans instead of vice versa?

In a nutshell, he concluded that societies developed differently on different continents not because of racial differences in attitudes or intelligence, but because of differences in continental environments. Advanced technology, centralized political organizations, writing, and professional armies (or simply put the military advantage of simply having large numbers of people), etc. could only emerge in dense, sedentary populations capable of accumulating food surpluses.

Unfortunately, domesticable wild plant and animal species needed for agriculture to arise were very unevenly distributed around the world, with the most valuable species concentrated in only nine small areas of the globe (Southwest Asia, China, Mesoamerica, the Andes and the adjacent Amazon basin, the eastern U.S., Africa's Sahel, West Africa, Ethiopia, and New Guinea), all of which became the earliest homelands of agriculture and thus regions that got a head start on developing guns, germs, and steel.

Animals were vital to a society as a source of meat, milk products, fertilizer, transportation, leather, for military use, plow traction, and wool and those areas that lacked suitable animals to domesticate suffered accordingly in terms of societal development. The Late Pleistocene extinctions of large mammals in the Americas and Australia deprived humanity in those areas of potentially very valuable domesticable species. Of the big (over 100 pound) herbivores and omnivores, 148 potential candidates for domestication, they are mostly located in Eurasia (72 candidate species, versus 51 in Sub-Saharan Africa, 24 in the Americas, and 1 in Australia). Further, out of those candidates, only 14 were actually domesticated, 13 of them in Eurasia; what he called the "Major Five" - sheep, the goat, cow, pig, and horse, and the "Minor Nine" - the Arabian camel, Bactrian camel, donkey, reindeer, water buffalo, yak, Bali cattle, mithan (wild ancestor the gaur, found primarily in India and Burma), and the one American one, the llama and alpaca (two well-differentiated breeds of the same species). The other 134 potential candidates were eliminated due to problems with diet, growth rate, problems of captive breeding, nasty disposition, tendency to panic, and/or social structure, any one problem enough to preclude domestication even in modern times. Of further interest, Southwest Asia had seven of the wild ancestors naturally occurring, a huge advantage.

In the world of plants there were similar disparities in distribution; of the 56 species of grass with the heaviest seeds, at least 10 times heavier than median species, Eurasia's Mediterranean zone had 32 of them, with barley and emmer wheat 3rd and 13th respectively in seed size. In contrast, of the 56 species, only 6 were found in East Asia, 4 in Sub-Saharan Africa, 11 in the Americas, and 2 in Australia.

Another set of differences lead to a variation in societal evolution in the case of plant and animal domestications as well as in technological innovations and political institutions, as most societies acquire much more from other societies than they invent themselves (his discussion on the evolution of writing and in particular the alphabet in this regard was fascinating). Diffusion and migration within and between continents played a very important role in the development of a society, and in some continents diffusion and migration was considerably easier, most rapid in Eurasia because of its east-west major axis and its relatively modest ecological and geographical barriers. As crops and animals depended strongly on climate and hence on latitude, huge areas ranging almost from the Atlantic to the Pacific were open to the movement of domesticated plants and animals. Diffusion was slower in Africa and especially in the Americas due to those continents north-south major axes (traveling just a few hundred or a thousand miles north or south can render a society's crops and animals completely unsuitable for use) and much more pronounced geographic and ecological barriers (such as the Sahara Desert in Africa). Similarly, diffusion in the last 6,000 years has been easiest from Eurasia to sub-Saharan Africa, while long completely absent between Eurasia and the Americas (isolated at low latitudes by broad oceans and at high latitudes by geography and by a climate suitable just for hunter-gatherers).

The last set of major factors he analyzed related to continental differences in area or total population size. A larger area or population meant more inventors, more competing societies, more innovations that exist to be adopted, and more pressure to adopt and retain those innovations, as those societies that fail to do so tend to be eliminated or absorbed by competing societies. Among the world's landmasses, area and the number of competing societies were greatest for Eurasia, while considerably smaller for Australia for instance. The Americas, despite their rather large total land area, were in effect fragmented by ecology and geography into a series of poorly connected smaller continents.

Relating to both population size and the "Eurasians' long intimacy with domestic animals" was the development of germs. Crowd diseases could not sustain themselves in small bands of hunter-gatherers or slash-and-burn farmers, nor perhaps would they develop at all, as only human association with cattle gave us for instance measles (evolved from rinderpest) and smallpox (evolved from cowpox).

Obviously I have just scratched the surface in my review. This is an excellent book that ties together findings in history, archaeology, paleontology, epidemiology, and linguistics in an extremely readable and informative format.

Read more

14 people found this helpful

gloine36

5

One of my favorite books and the inspiration for my World Regional Geography courses that I teach.

Reviewed in the United States on September 5, 2015

Verified Purchase

Two decades ago when I served in the Missouri National Guard we had an extended drill weekend at Ft. Leonard Wood for a live fire artillery exercise. This was a three day drill and I remember it clearly because it was the same weekend as Princess Diana’s funeral on September 6, 1997. I had been at the local library the day before we rolled out and saw an interesting book that promised to explain why western civilization had been the one to colonize the New World and rise to ascendency over much of the world for a long period of time. That had always been an interesting question for me and one which many people do not know the answer to. I checked out the book and during some downtime I began to read. To say that the book grabbed my attention is an understatement. I started it on Friday and finished it on Saturday. My whole conception of how history had seen the rise of Western Civilization was fundamentally altered and would never be the same.

At the time I thought that using Guns, Germs, and Steel as an educational tool would be a great idea. My dream of teaching history had never been realized and in 1997 seemed like it would never happen. However, history is full of strange things and in 2009 I got the chance to return to college and pick up my degrees. I began teaching American History in 2013 and was then asked to teach World Regional Geography for the Spring 2014 semester. They handed me a textbook and said, “Good luck.” As I drove back home I considered how I would teach this course and my mind recalled Jared Diamond and his Pulitzer Prize winning book. To make the story short, I built a course that used the textbook, Diamond’s book, and the National Geographic series based on the book.

Obviously I take what Diamond said in Guns, Germs, and Steel seriously. I think Diamond did some outstanding work in doing three decades of research and then writing a book which to me is resonates with readers. For many years the idea that Western Civilization was superior to any other form has been the dominant world view. Diamond rejects that completely by saying Western Civilization had advantages that others did not have due to geography, or literally where it was. When you stop and think about it, why were the Europeans so superior to others for so long? Was it their race, their ideals, or what? Diamond said it was because of where they started that they developed into the world spanning civilization we know.

What advantages did the Europeans have over others? They arrived with technology superior to all others, were better organized, and had the lethal gift of germs which in the Americas killed over half the population and was the biggest reason as to why the Europeans took those lands over. When Diamond explored the germ theory he realized that these germs came from contact with domesticated mammals such as horses, cows, pigs, chickens, sheep, and goats. These same mammals were what enabled Europeans to transport materials as well as have a convenient food supply and a power source such as horses pulling plows.

This idea works when you look at the Americas and Australia, but not when you look at Africa and Asia. The lethality of germs did not affect the people in those regions like it did the Americas. In fact, some of the diseases in Africa killed the Europeans and prevented them for exploiting Sub-Saharan Africa for centuries. Some of these germs are now known to have come from Asia as well along with domestic animals that came from there. Many of the larger mammals Europe had were also found in Asia. In fact, some of the technology such as gunpowder came from Asia as well. Diamond acknowledged this in his book and sought to explain why Europe was able to expand while Asia did not.

This is something I really stress in my class and it is something which the book and National Geographic series does not explore as deeply as it should. Diamond saw a decision made in the 15th century by a Chinese emperor as being the decisive event that altered human history. At that point China was the leading power in the world. It had a great navy, the largest country, gunpowder, advanced technology and far more people thanks to its agricultural practices than any other nation at that time. The decision by emperors in China’s Ming dynasty led to China losing its technological advantage over Europe although no one had any idea that this was happening. These decisions or orders are called Haijin.

Diamond did not explore this in any depth other than to point to it and say that China’s inward looking policies which had existed for centuries were the result of its location, its geography. Its singular form of government used Haijin to build up its power at the expense of expanding China’s culture and boundaries. There is a lot here to work with, but Diamond seems to casually bring it up in the book’s epilogue. Instead he focuses heavily on the Americas where his theory of environmental determinism is the strongest. I think he gets the theory right, but in the case of Asia he needed to go deeper.

Since Diamond is an ornithologist by education, and his world journey’s focused on New Guinea, I think his point of view was heavily influenced through his contact with hunter-gatherers. His theory is at its weakest in Asia and specifically China. That again reflects his preference for focusing on one type of people versus another. This does not mean his theory is wrong. It just needs expansion and I do not think Diamond will be doing that any time soon. His recent works have dealt with different ideas.

Even with this glaring problem, I think this book is outstanding. It does answer the question of why Western Civilization dominated the world for the most part. For my geography class it is a wonderful tool. I focus heavily on how man domesticated two grains from the Middle East, wheat and barley, and built Western Civilization upon them. Coupled with the domestication of large mammals, the forerunners of Western Civilization spread through Europe. Geography played a huge role in why it went west and why there are so many differences between East and West on a cultural level. It also explains why there are such huge differences between North Africa and the lands to the south of the Sahara.

The role of geography in shaping mankind is without a doubt the single underlying reason as to why history occurred like it did. This is really hard for students to understand because they seem to have been taught a much different concept prior to taking a geography course. Only by explaining the human-environment interaction do students begin to realize that geography caused man to make decisions which would reverberate for millennia. The people of the Middle East followed the Tigris and Euphrates rivers northwest into Anatolia and out of the desert. Man’s movement west, north, and south with the crops and animals of the Middle East were shaped by geographical barriers.

Diamond points out how man overcame these barriers over time. The civilization that was able to do so developed greater technologies than others. He points to both European and Chinese naval developments in this regard. China’s need to continue to build its naval forces was negligible due to a lack of naval enemies while in Europe those enemies were often themselves as nations competed for resources and trade. Since China controlled all of its trade which was mostly internal or land based, its need for a navy was reduced. Europe surged ahead while China languished.

In my classes I point to the barriers as we explore the world’s regions. I show how these barriers played such big roles. We play a board game by Avalon Hill that helps to illustrate this as well. Diamond’s book plays a big role in my class and so do his theories. I find it really helps students take the principles and ideas from the first part of the class and begin to apply them to the world regions we study. They are able to make the mental leap to the realization that the people of the world are different for many reasons, the foremost being the place in which they live more than anything else. It helps them to break down and discard the erroneous belief which many of them have regarding their place in the world. Using Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel I am able to use Transformative Learning Theory to overcome the disorientating dilemma they find themselves in at the beginning of class.

I could build a new class out of Diamond’s book that encompasses geography, history, and sociology if my school would let me. In fact, I could build two classes out of it. One would focus on why Western Civilization developed like it did and expanded to the Americas while the second one would focus on the development of Eastern Civilization and its failure to expand beyond Asia itself. While courses exist that dive into those ideas, they are built around history more than anything else. Few instructors use environmental determinism in explaining how early mankind developed in the places it did. The ultimate objectives of these courses would be why they developed like they did, not just their history.

Diamond has written several other books such as Collapse, The Third Chimpanzee, and The World Until Yesterday. He is Professor of Geography at the University of California, Los Angeles. He has been awarded all kinds of prizes and awards for his research and work in multiple fields. I find it interesting that he began to study environmental history in his fifties which led to this book and many others. This to me is proof that you are not bound by formal rules regarding your education, but rather by using your interests coupled with the research capabilities your education has provided you new careers beckon. This book is a testament to following one’s interests and using one’s intellect. I highly recommend it to all readers. It is one of my favorite books and I have read through it multiple times.

Read more

129 people found this helpful

LA in Dallas

5

The biology of history

Reviewed in the United States on September 11, 2023

Verified Purchase

I think I read Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies for the first time shortly after it won a 1998 Pulitzer Prize. I was at the time a Professor of Molecular Biology. I found it fascinating. I later recommended it to a book club I belonged to -- most of the other members were businesspeople. Most of them also enjoyed it. Jared Diamond is not always right, and you will not always agree with his ideas. But he is always intelligent and lucid, and, in my opinion and the opinions of the Biz School friends, he writes well.

These positive reactions are not universal. Diamond is not a historian or an anthropologist -- he's an evolutionary biologist. He does something to history that you might expect a person with a background in the so-called hard sciences to do: he tries to find broadly applicable theories to explain history. In Physics, Chemistry, and Biology this is the name of the game. But many professional historians passionately hate the idea of broad theories of history. Beyond that -- here's a broadly applicable theory -- groups of people tend to have a powerful impetus to defend their borders. I guarantee you that if a historian writes an insightful and popular book about biology that upsets existing dogma, hordes of biologists will rise in rabid rage to denounce the intruder. (I might even be one of them.)

That, in my opinion after a quick survey of some of the negative reviews, is what most of them are. These opinions should not be ignored. Some of the more thoughtful reviews (sadly, only a small minority of the one-star reviews deserve the adjective "thoughtful") make good points between the screams of primal rage.

There is, I think, one respect in which Diamond is certainly right. History is biology: human biology, the biology of the animals and plants with which we live, and the biology of the viruses, bacteria, and parasites that prey on us. It is not JUST biology, but the importance of our underlying biology is emphasized in any view of history that extends over the Holocene epoch. Now, while I suspect almost every historian would agree in principle with the statement that humans are living things, therefore have biology, and that biology plays some kind of role in history, works of mainstream history that discuss the impact of biology on history are vanishingly rare. In describing the biology of history, Diamond pushes the discipline in a direction it needs to go.

But I WOULD say that, right? I'm a self-confessed biologist.

Read more

15 people found this helpful

Zachary Ruesch

5

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies

Reviewed in the United States on June 27, 2016

Verified Purchase

Recently, I finished this great, broad, historical, and significant endeavor. Let me begin by expressing my appreciation of Jared Diamond’s wonderful ability to simplify a very complex topic and related ideas. This alone, makes this read a great one. Too, there a few gems of humor and wit within the pages which caught my eye and mind. Don’t get me wrong though. The pages are filled with complex data, examples, and comparisons. Upon more than one occasion, my understanding necessitated the rereading of paragraphs and pages.

Before I proceed into deeper thoughts, I must admit the duration of this read as being conducted well over an extended timeframe. I began reading it years ago, stopped, and then started again. Over the course of the last several months, I recommitted and achieved.

In thoughtful detail, Diamond seeks to explain why certain groups of people have been successful over the course of human events and history, while others, in comparison, are not. It should be noted, the idea of “success” is very subjective. So, success in this case, is related to Western ideas of technological development, exploration, and conquest - generally described as one group of people gaining control or influence over another. An effective description of this is the Spanish conquest and colonization of the “New World,” especially the Aztecs and Incas. This example, though quite large in scope, and as pointed out by Diamond, has occurred throughout human history in large and small ways involving a multitude of others groups of people, both known and unknown.

In short, I believe Diamond does well in addressing the impact and luck of geography and resources, as well as, the influences of more innate human characteristics and variety. The debate of nature versus nurture is here too contained. In the past, and not only in recent history, humans have expressed understandings of success in terms of innate differences which must exist between people - obviously though, those in power and dominate are able to define and express such ideas. However, Diamond looks beyond this and recognizes the complexity, and ultimately more profound influence of reality, nurture. In this sense though, it is not simply human nurturing and choice, it is the opportunities presented to humans, in difference places, at different times, to take advantage of their earthly surroundings and the ability to nurture developments, or not.

This read is filled with a plethora of well detailed examples which come to show how access, or not, to certain elements leads to the success and superiority which has been described and known by those in power, throughout history. So, today, when certain people look down upon others and their lack of some qualities or characteristics, Diamond’s historical analysis provides engaging insight beyond and through the bias.

Who we are presently is the result of all the past experiences of the human ancestors who preceded us, and furthermore, our development and success, in comparison to other humans, is simply more so the result of the access we have had to a confluence of resources and circumstances which allowed us to dominate other groups of humans with less access to the same. As groups of humans defined through sociological processes, we are no more intelligent, healthy, or physiologically better than the whole of humanity understood to exist through anthropology, biology, and any other area of study.

“We all know that history has proceeded very differently for peoples from different parts of the globe...Those historical inequalities have cast long shadows on the modern world, because the literate societies with metal tools have conquered or exterminated the other societies. While those differences constitute the most basic fact of world history, the reasons for them remain uncertain and controversial.” In this work, Diamond splendidly explains how, “History followed different courses for different peoples because of differences among peoples’ environments, not because of biological differences among peoples themselves.”

Please give the ideas of these pages the opportunity to share with you a detailed perspective of human experience which reaches far into the depths of history, beyond even the earliest written language. Diamond’s words will likely cause you to become lost in thoughts of the past. However, at the same time, he’ll take you to definitive places of demonstrable purpose leading to a better future understood through the context(s) of human experience.

Read more

7 people found this helpful

mtspace

4

Monumental Thesis, Richly Researched & Carefully Argued

Reviewed in the United States on September 7, 2005

Verified Purchase

Motivating this book are two questions 1) When Spanish conquistador Pizzaro encountered Inca emperor Atahualpa, how did the former, with fewer than two hundred men overwhelm the latter with over 80,000? and 2) When the Europeans set up colonies on the island of new Guinea, why was it that they had so much stuff to trade, but the natives of the island had so little?

The answer to the first question is, of course, that the Spanish had Guns, Germs, and Steel. Diamond does an outstanding job arguing for the pivotal importance of Germs in the equation. He clearly explains - using the idea of germs - why Europeans overran the Americas and Australia but not Africa. His agument regarding steel is notably weaker; but I think it does support his thesis adequately. I failed to detect a compelling argument for why Europeans had guns but others did not.

The book's primary focus is on how civilization got started. He looks first at the cultivation of plants and then at the domestication of animals. Examining areas in Africa, Eurasia, the Americas, and Australia, he totes up the lists of suitable flora and fauna and evaluates their merits. He notes that it was the fertile crescent that harbored the most suitable grains, legumes (or pulses), and domesticable animals. No other location comes close to having this rich combination of natural resources. He shows that this explains the very early appearance of agricutlure and therefore of writing, religion, and law in this area (and in China).

He also shows how any human advancement would spread more quickly in Eurasia than it would within the Americas and Africa. This gives Eurasia a double advantage; it can harbor more people by virtue of its agricultural practices and each person has greater access to new ideas because of strong east-west trade currents. Thus cultures in Eurasia could easily adapt ideas based on those of other societies instead of creating them from scratch.

He concludes that any person who accepts his thesis of the forces shaping civilization - at least the necessary precondition to get started - would necessarily conclude that civilization's advances must inevitably run quickest on the Eurasian continent.

A large portion of the book is focussed on the factors influencing the establishement of an agricultural system that is capable of supporting a whole large class of non-agricultural workers. The assumption, I believe, is that we already know that this is the primary requirement for the birth of a civilization. Still I was looking forward to Diamond's take on what happens after we all learn to read and write. I was hoping he might explain the ascent of the west since 1000 BC or 1500 AD. But he does not.

He does not, for instance, argue why it was the British and Spanish, not the Turks and Indians who settled Australia and the Americas. This, perhaps is a different question. Yet it seems to be linked to the idea of frontiers and access to resources. For it is always when the full set of advanced cultural practices reach populations in the richest, most uncultivated frontiers and these ideas cast anew in the light of a new environment that civilization seems to gain its greatest momentum.

He uses Polynesia as a microcosm for the world. In this laboratory, a group of people with the same genetic cross-section and same cultural practices embarked on a grand venture to settle all the islands of the Pacific some two millenia ago or so. The systems of government they set up and the level of civilization they reached were highly dependent upon the agricultual productivity of their citizens. Colonists on small islands unsuitable for agriculture became hunter-gatherers and lived in egalitarian societies. Those in productive lands organized into small states with strong chiefs or kings, each with their own little standing armies.

The book is richly researched and solidly argued as far as it goes. But there are a handful of quibbles one might raise.

-

The author tends to repeat himself. As the book progresses, the portion of prose that is a restatement of something said before becomes so high that this reader found himself skipping whole chapters.

-

The author fails to provide a compelling argument about why China lagged Europe at some point after 1500. One wonders why the author did not simply use the argument at hand. Colonialism provided to Europe the raw materials necessary for industrial production. China was closed until two or three decades ago and so did not have adequate access to the raw materials that vaulted Europe and North America to their current place. The opening of China to the world has quickly closed this gap. In other words, the cultural practice that gave frontier states the advantage was the high value they realized in trade: of getting required natural resources and finished goods from other places instead of being closed off. The book's central thesis is that the first and most necessary condition for the success of a society lies in its access to the required resources, and that transport of goods and ideas is crucial to the success of this enterprise. For this book to fail to make this connection I find to be an astonishing lapse.

-

Unless it is hidden in one of the skipped chapters, Diamond never starts to answer the second motivating question about 'stuff', even though it is a simple and direct extension of his fairly robust argument.

This book is of crucial importance in counter-balancing our Darwinian view of the world. It was not that Europeans were better people by some genetic measure. (Darwin seemed to assume a single measure of fitness. But each environmental variable provides a different metric of fitness so the whole notion of one group being generally 'more fit' is utter nonsense.) It was that they had a body of technologies, cultural practices and diseases that naturally tended to overwhelm other groups. And that these ideas and practices (and sometimes diseases) are an inevitable advantage any agrarian or post agrarian society has over a less highly organized one. Europeans simply got a head start thanks to geography.

There is much to learn, and much to contemplate in this book. Read It.

Read more

10 people found this helpful

Best Sellers

The Great Alone: A Novel

4.6

-

152,447

$5.49

The Four Winds

4.6

-

156,242

$9.99

Winter Garden

4.6

-

72,838

$7.37

The Nightingale: A Novel

4.7

-

309,637

$8.61

Steve Jobs

4.7

-

24,596

$1.78

Iron Flame (The Empyrean, 2)

4.6

-

164,732

$14.99

A Court of Thorns and Roses Paperback Box Set (5 books) (A Court of Thorns and Roses, 9)

4.8

-

26,559

$37.99

Pretty Girls: A Novel

4.3

-

88,539

$3.67

The Bad Weather Friend

4.1

-

34,750

$12.78

Pucking Around: A Why Choose Hockey Romance (Jacksonville Rays Hockey)

4.3

-

41,599

$14.84

Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action

4.6

-

37,152

$9.99

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow: A novel

4.4

-

95,875

$13.99

Weyward: A Novel

4.4

-

27,652

$11.99

Tom Lake: A Reese's Book Club Pick

4.3

-

37,302

$15.74

All the Sinners Bleed: A Novel

4.4

-

12,894

$13.55

The Mystery Guest: A Maid Novel (Molly the Maid)

4.3

-

9,844

$14.99

Bright Young Women: A Novel

4.2

-

8,485

$14.99

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder (Random House Large Print)

4.5

-

28,672

$14.99

Hello Beautiful (Oprah's Book Club): A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.4

-

79,390

$14.99

Small Mercies: A Detective Mystery

4.5

-

16,923

$10.00

Holly

4.5

-

31,521

$14.99

The Covenant of Water (Oprah's Book Club)

4.6

-

69,712

$9.24

Wellness: A novel

4.1

-

3,708

$14.99

The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession

4.3

-

4,805

$14.99