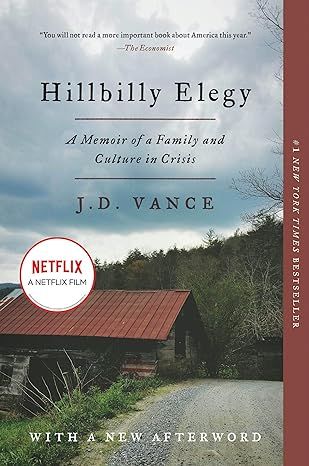

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis

4.4

-

100,659 ratings

Hillbilly Elegy recounts J.D. Vance's powerful origin story...

From a former marine and Yale Law School graduate now serving as a U.S. Senator from Ohio and the Republican Vice Presidential candidate for the 2024 election, an incisive account of growing up in a poor Rust Belt town that offers a broader, probing look at the struggles of America's white working class.

THE #1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

"You will not read a more important book about America this year."—The Economist

"A riveting book."—The Wall Street Journal

"Essential reading."—David Brooks, New York Times

Hillbilly Elegy is a passionate and personal analysis of a culture in crisis—that of white working-class Americans. The disintegration of this group, a process that has been slowly occurring now for more than forty years, has been reported with growing frequency and alarm, but has never before been written about as searingly from the inside. J. D. Vance tells the true story of what a social, regional, and class decline feels like when you were born with it hung around your neck.

The Vance family story begins hopefully in postwar America. J. D.'s grandparents were "dirt poor and in love," and moved north from Kentucky's Appalachia region to Ohio in the hopes of escaping the dreadful poverty around them. They raised a middle-class family, and eventually one of their grandchildren would graduate from Yale Law School, a conventional marker of success in achieving generational upward mobility. But as the family saga of Hillbilly Elegy plays out, we learn that J.D.'s grandparents, aunt, uncle, and, most of all, his mother struggled profoundly with the demands of their new middle-class life, never fully escaping the legacy of abuse, alcoholism, poverty, and trauma so characteristic of their part of America. With piercing honesty, Vance shows how he himself still carries around the demons of his chaotic family history.

A deeply moving memoir, with its share of humor and vividly colorful figures, Hillbilly Elegy is the story of how upward mobility really feels. And it is an urgent and troubling meditation on the loss of the American dream for a large segment of this country.

Read more

Kindle

$14.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$20.38

Paperback

$11.53

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

0062300555

ISBN-13

978-0062300553

Print length

288 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Harper Paperbacks

Publication date

April 30, 2018

Dimensions

5.31 x 0.72 x 8 inches

Item weight

2.31 pounds

Popular highlights in this book

There is a lack of agency here—a feeling that you have little control over your life and a willingness to blame everyone but yourself.

Highlighted by 5,849 Kindle readers

It’s about a culture that increasingly encourages social decay instead of counteracting it.

Highlighted by 5,207 Kindle readers

There is a cultural movement in the white working class to blame problems on society or the government, and that movement gains adherents by the day.

Highlighted by 5,101 Kindle readers

What separates the successful from the unsuccessful are the expectations that they had for their own lives. Yet the message of the right is increasingly: It’s not your fault that you’re a loser; it’s the government’s fault.

Highlighted by 4,702 Kindle readers

Product details

ASIN :

0062300555

File size :

2706 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Editorial reviews

“[A] compassionate, discerning sociological analysis…Combining thoughtful inquiry with firsthand experience, Mr. Vance has inadvertently provided a civilized reference guide for an uncivilized election, and he’s done so in a vocabulary intelligible to both Democrats and Republicans. Imagine that.” — Jennifer Senior, New York Times

“[Hillbilly Elegy] is a beautiful memoir but it is equally a work of cultural criticism about white working-class America….[Vance] offers a compelling explanation for why it’s so hard for someone who grew up the way he did to make it…a riveting book.” — Wall Street Journal

“[Vance’s] description of the culture he grew up in is essential reading for this moment in history.” — David Brooks, New York Times

“[Hillbilly Elegy] couldn’t have been better timed...a harrowing portrait of much that has gone wrong in America over the past two generations...an honest look at the dysfunction that afflicts too many working-class Americans.” — National Review

"[A]n American classic, an extraordinary testimony to the brokenness of the white working class, but also its strengths. It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read… [T]he most important book of 2016. You cannot understand what’s happening now without first reading J.D. Vance." — Rod Dreher,The American Conservative

“J.D. Vance’s memoir, “Hillbilly Elegy”, offers a starkly honest look at what that shattering of faith feels like for a family who lived through it. You will not read a more important book about America this year.” — The Economist

“[A] frank, unsentimental, harrowing memoir...a superb book...” — New York Post

“The troubles of the working poor are well known to policymakers, but Vance offers an insider’s view of the problem.” — Christianity Today

“Vance movingly recounts the travails of his family.” — Washington Post

“What explains the appeal of Donald Trump? Many pundits have tried to answer this question and fallen short. But J.D. Vance nails it...stunning...intimate...” — Globe and Mail (Toronto)

“[A] new memoir that should be read far and wide.” — Institute of Family Studies

“[An] understated, engaging debut...An unusually timely and deeply affecting view of a social class whose health and economic problems are making headlines in this election year.” — Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Both heartbreaking and heartwarming, this memoir is akin to investigative journalism. … A quick and engaging read, this book is well suited to anyone interested in a study of modern America, as Vance’s assertions about Appalachia are far more reaching.” — Library Journal

“Vance compellingly describes the terrible toll that alcoholism, drug abuse, and an unrelenting code of honor took on his family, neither excusing the behavior nor condemning it…The portrait that emerges is a complex one…Unerringly forthright, remarkably insightful, and refreshingly focused, Hillbilly Elegy is the cry of a community in crisis.” — Booklist

To understand the rage and disaffection of America’s working-class whites, look to Greater Appalachia. In HILLBILLY ELEGY, J.D. Vance confronts us with the economic and spiritual travails of this forgotten corner of our country. Here we find women and men who dearly love their country, yet who feel powerless as their way of life is devastated. Never before have I read a memoir so powerful, and so necessary. — Reihan Salam, executive editor, National Review

“A beautifully and powerfully written memoir about the author’s journey from a troubled, addiction-torn Appalachian family to Yale Law School, Hillbilly Elegy is shocking, heartbreaking, gut-wrenching, and hysterically funny. It’s also a profoundly important book, one that opens a window on a part of America usually hidden from view and offers genuine hope in the form of hard-hitting honesty. Hillbilly Elegy announces the arrival of a gifted and utterly original new writer and should be required reading for everyone who cares about what’s really happening in America.” — Amy Chua, New York Times bestselling author of The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother

“Elites tend to see our social crisis in terms of ‘stagnation’ or ‘inequality.’ J. D. Vance writes powerfully about the real people who are kept out of sight by academic abstractions.” — Peter Thiel, entrepreneur, investor, and author of Zero to One

Read more

Sample

Chapter 1

Like most small children, I learned my home address so that if I got lost, I could tell a grown-up where to take me. In kindergarten, when the teacher asked me where I lived, I could recite the address without skipping a beat, even though my mother changed addresses frequently, for reasons I never understood as a child. Still, I always distinguished “my address” from “my home.” My address was where I spent most of my time with my mother and sister, wherever that might be. But my home never changed: my great-grandmother’s house, in the holler, in Jackson, Kentucky.

Jackson is a small town of about two thousand in the heart of southeastern Kentucky’s coal country. Calling it a town is a bit charitable: There’s a courthouse, a few restaurants—almost all of them fast-food chains—and a few other shops and stores. Most of the people live in the mountains surrounding Kentucky Highway 15, in trailer parks, in government-subsidized housing, in small farmhouses, and in mountain homesteads like the one that served as the backdrop for the fondest memories of my childhood.

Jacksonians say hello to everyone, willingly skip their favorite pastimes to dig a stranger’s car out of the snow, and—without exception—stop their cars, get out, and stand at attention every time a funeral motorcade drives past. It was that latter practice that made me aware of something special about Jackson and its people. Why, I’d ask my grandma—whom we all called Mamaw—did everyone stop for the passing hearse? “Because, honey, we’re hill people. And we respect our dead.”

My grandparents left Jackson in the late 1940s and raised their family in Middletown, Ohio, where I later grew up. But until I was twelve, I spent my summers and much of the rest of my time back in Jackson. I’d visit along with Mamaw, who wanted to see friends and family, ever conscious that time was shortening the list of her favorite people. And as time wore on, we made our trips for one reason above all: to take care of Mamaw’s mother, whom we called Mamaw Blanton (to distinguish her, though somewhat confusingly, from Mamaw). We stayed with Mamaw Blanton in the house where she’d lived since before her husband left to fight the Japanese in the Pacific.

Mamaw Blanton’s house was my favorite place in the world, though it was neither large nor luxurious. The house had three bedrooms. In the front were a small porch, a porch swing, and a large yard that stretched into a mountain on one side and to the head of the holler on the other. Though Mamaw Blanton owned some property, most of it was uninhabitable foliage. There wasn’t a backyard to speak of, though there was a beautiful mountainside of rock and tree. There was always the holler, and the creek that ran alongside it; those were backyard enough. The kids all slept in a single upstairs room: a squad bay of about a dozen beds where my cousins and I played late into the night until our irritated grandma would frighten us into sleep.

The surrounding mountains were paradise to a child, and I spent much of my time terrorizing the Appalachian fauna: No turtle, snake, frog, fish, or squirrel was safe. I’d run around with my cousins, unaware of the ever-present poverty or Mamaw Blanton’s deteriorating health.

At a deep level, Jackson was the one place that belonged to me, my sister, and Mamaw. I loved Ohio, but it was full of painful memories. In Jackson, I was the grandson of the toughest woman anyone knew and the most skilled auto mechanic in town; in Ohio, I was the abandoned son of a man I hardly knew and a woman I wished I didn’t. Mom visited Kentucky only for the annual family reunion or the occasional funeral, and when she did, Mamaw made sure she brought none of the drama. In Jackson, there would be no screaming, no fighting, no beating up on my sister, and especially “no men,” as Mamaw would say. Mamaw hated Mom’s various love interests and allowed none of them in Kentucky.

In Ohio, I had grown especially skillful at navigating various father figures. With Steve, a midlife-crisis sufferer with an earring to prove it, I pretended earrings were cool—so much so that he thought it appropriate to pierce my ear, too. With Chip, an alcoholic police officer who saw my earring as a sign of “girlieness,” I had thick skin and loved police cars. With Ken, an odd man who proposed to Mom three days into their relationship, I was a kind brother to his two children. But none of these things were really true. I hated earrings, I hated police cars, and I knew that Ken’s children would be out of my life by the next year. In Kentucky, I didn’t have to pretend to be someone I wasn’t, because the only men in my life—my grandmother’s brothers and brothers-in-law—already knew me. Did I want to make them proud? Of course I did, but not because I pretended to like them; I genuinely loved them.

The oldest and meanest of the Blanton men was Uncle Teaberry, nicknamed for his favorite flavor of chewing gum. Uncle Teaberry, like his father, served in the navy during World War II. He died when I was four, so I have only two real memories of him. In the first, I’m running for my life, and Teaberry is close behind with a switchblade, assuring me that he’ll feed my right ear to the dogs if he catches me. I leap into Mamaw Blanton’s arms, and the terrifying game is over. But I know that I loved him, because my second memory is of throwing such a fit over not being allowed to visit him on his deathbed that my grandma was forced to don a hospital robe and smuggle me in. I remember clinging to her underneath that hospital robe, but I don’t remember saying goodbye.

Uncle Pet came next. Uncle Pet was a tall man with a biting wit and a raunchy sense of humor. The most economically successful of the Blanton crew, Uncle Pet left home early and started some timber and construction businesses that made him enough money to race horses in his spare time. He seemed the nicest of the Blanton men, with the smooth charm of a successful businessman. But that charm masked a fierce temper. Once, when a truck driver delivered supplies to one of Uncle Pet’s businesses, he told my old hillbilly uncle, “Off-load this now, you son of a bitch.” Uncle Pet took the comment literally: “When you say that, you’re calling my dear old mother a bitch, so I’d kindly ask you speak more carefully.” When the driver—nicknamed Big Red because of his size and hair color—repeated the insult, Uncle Pet did what any rational business owner would do: He pulled the man from his truck, beat him unconscious, and ran an electric saw up and down his body. Big Red nearly bled to death but was rushed to the hospital and survived. Uncle Pet never went to jail, though. Apparently, Big Red was also an Appalachian man, and he refused to speak to the police about the incident or press charges. He knew what it meant to insult a man’s mother.

Uncle David may have been the only one of Mamaw’s brothers to care little for that honor culture. An old rebel with long, flowing hair and a longer beard, he loved everything but rules, which might explain why, when I found his giant marijuana plant in the backyard of the old homestead, he didn’t try to explain it away. Shocked, I asked Uncle David what he planned to do with illegal drugs. So he got some cigarette papers and a lighter and showed me. I was twelve. I knew if Mamaw ever found out, she’d kill him.

I feared this because, according to family lore, Mamaw had nearly killed a man. When she was around twelve, Mamaw walked outside to see two men loading the family’s cow—a prized possession in a world without running water—into the back of a truck. She ran inside, grabbed a rifle, and fired a few rounds. One of the men collapsed—the result of a shot to the leg—and the other jumped into the truck and squealed away. The would-be thief could barely crawl, so Mamaw approached him, raised the business end of her rifle to the man’s head, and prepared to finish the job. Luckily for him, Uncle Pet intervened. Mamaw’s first confirmed kill would have to wait for another day.

Even knowing what a pistol-packing lunatic Mamaw was, I find this story hard to believe. I polled members of my family, and about half had never heard the story. The part I believe is that she would have murdered the man if someone hadn’t stopped her. She loathed disloyalty, and there was no greater disloyalty than class betrayal. Each time someone stole a bike from our porch (three times, by my count), or broke into her car and took the loose change, or stole a delivery, she’d tell me, like a general giving his troops marching orders, “There is nothing lower than the poor stealing from the poor. It’s hard enough as it is. We sure as hell don’t need to make it even harder on each other.”

Youngest of all the Blanton boys was Uncle Gary. He was the baby of the family and one of the sweetest men I knew. Uncle Gary left home young and built a successful roofing business in Indiana. A good husband and a better father, he’d always say to me, “We’re proud of you, ole Jaydot,” causing me to swell with pride. He was my favorite, the only Blanton brother not to threaten me with a kick in the ass or a detached ear.

My grandma also had two younger sisters, Betty and Rose, whom I loved each very much, but I was obsessed with the Blanton men. I would sit among them and beg them to tell and retell their stories. These men were the gatekeepers to the family’s oral tradition, and I was their best student.

Most of this tradition was far from child appropriate. Almost all of it involved the kind of violence that should land someone in jail. Much of it centered on how the county in which Jackson was situated—Breathitt—earned its alliterative nickname, “Bloody Breathitt.” There were many explanations, but they all had one theme: The people of Breathitt hated certain things, and they didn’t need the law to snuff them out.

One of the most common tales of Breathitt’s gore revolved around an older man in town who was accused of raping a young girl. Mamaw told me that, days before his trial, the man was found facedown in a local lake with sixteen bullet wounds in his back. The authorities never investigated the murder, and the only mention of the incident appeared in the local newspaper on the morning his body was discovered. In an admirable display of journalistic pith, the paper reported: “Man found dead. Foul play expected.” “Foul play expected?” my grandmother would roar. “You’re goddamned right. Bloody Breathitt got to that son of a bitch.”

Or there was that day when Uncle Teaberry overheard a young man state a desire to “eat her panties,” a reference to his sister’s (my Mamaw’s) undergarments. Uncle Teaberry drove home, retrieved a pair of Mamaw’s underwear, and forced the young man—at knifepoint—to consume the clothing.

Some people may conclude that I come from a clan of lunatics. But the stories made me feel like hillbilly royalty, because these were classic good-versus-evil stories, and my people were on the right side. My people were extreme, but extreme in the service of something—defending a sister’s honor or ensuring that a criminal paid for his crimes. The Blanton men, like the tomboy Blanton sister whom I called Mamaw, were enforcers of hillbilly justice, and to me, that was the very best kind. Despite their virtues, or perhaps because of them, the Blanton men were full of vice. A few of them left a trail of neglected children, cheated wives, or both. And I didn’t even know them that well: I saw them only at large family reunions or during the holidays. Still, I loved and worshipped them. I once overheard Mamaw tell her mother that I loved the Blanton men because so many father figures had come and gone, but the Blanton men were always there. There’s definitely a kernel of truth to that. But more than anything, the Blanton men were the living embodiment of the hills of Kentucky. I loved them because I loved Jackson.

As I grew older, my obsession with the Blanton men faded into appreciation, just as my view of Jackson as some sort of paradise matured. I will always think of Jackson as my home. It is unfathomably beautiful: When the leaves turn in October, it seems as if every mountain in town is on fire. But for all its beauty, and for all the fond memories, Jackson is a very harsh place. Jackson taught me that “hill people” and “poor people” usually meant the same thing. At Mamaw Blanton’s, we’d eat scrambled eggs, ham, fried potatoes, and biscuits for breakfast; fried bologna sandwiches for lunch; and soup beans and cornbread for dinner. Many Jackson families couldn’t say the same, and I knew this because, as I grew older, I overheard the adults speak about the pitiful children in the neighborhood who were starving and how the town could help them. Mamaw shielded me from the worst of Jackson, but you can keep reality at bay only so long.

On a recent trip to Jackson, I made sure to stop at Mamaw Blanton’s old house, now inhabited by my second cousin Rick and his family. We talked about how things had changed. “Drugs have come in,” Rick told me. “And nobody’s interested in holding down a job.” I hoped my beloved holler had escaped the worst, so I asked Rick’s boys to take me on a walk. All around I saw the worst signs of Appalachian poverty.

Some of it was as heartbreaking as it was cliché: decrepit shacks rotting away, stray dogs begging for food, and old furniture strewn on the lawns. Some of it was far more troubling. While passing a small two-bedroom house, I noticed a frightened set of eyes looking at me from behind the curtains of a bedroom window. My curiosity piqued, I looked closer and counted no fewer than eight pairs of eyes, all looking at me from three windows with an unsettling combination of fear and longing. On the front porch was a thin man, no older than thirty-five, apparently the head of the household. Several ferocious, malnourished, chained-up dogs protected the furniture strewn about the barren front yard. When I asked Rick’s son what the young father did for a living, he told me the man had no job and was proud of it. But, he added, “they’re mean, so we just try to avoid them.”

That house might be extreme, but it represents much about the lives of hill people in Jackson. Nearly a third of the town lives in poverty, a figure that includes about half of Jackson’s children. And that doesn’t count the large majority of Jacksonians who hover around the poverty line. An epidemic of prescription drug addiction has taken root. The public schools are so bad that the state of Kentucky recently seized control. Nevertheless, parents send their children to these schools because they have little extra money, and the high school fails to send its students to college with alarming consistency. The people are physically unhealthy, and without government assistance they lack treatment for the most basic problems. Most important, they’re mean about it—they will hesitate to open their lives up to others for the simple reason that they don’t wish to be judged.

Read more

About the authors

J.D. Vance

J. D. Vance grew up in the Rust Belt city of Middletown, Ohio, and the Appalachian town of Jackson, Kentucky. He enlisted in the Marine Corps after high school and served in Iraq. A graduate of Ohio State University and Yale Law School, he was elected to the United States Senate representing Ohio in 2022. In 2024, he became the Republican nominee for Vice President. Vance lives in Columbus, Ohio, with his family.

Read more

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.4 out of 5

100,659 global ratings

Sandy Powers

5

Deeply impactful!

Reviewed in the United States on July 18, 2024

Verified Purchase

Wow! I went to check out the book from my free Library app as soon as I learned J.D. Vance was nominated to run for the Vice Presidency. My app noted “We have 50 copies of this book and 393 waiting to read it”. Curiously, I checked the next day. They bought more copies of the book but the note read: “We have 165 copies of the book and 225 waiting in line to read it”!!!! And that’s just from the San Antonio Library! So I bought the book on Amazon and couldn’t put it down, reading it in 2 days!

It’s heartbreaking what he and his sister had to endure as children! And yet, one paragraph in the book says so much about the contradiction of abuse and deep love and loyalty in his family. In Marine boot camp, most of the recruits received 1 or 2 letters from home a week. But J.D. received stacks of mail every day from family members encouraging him, telling him how proud they were of him, how much they loved him. How many families of privilege would give anything to have that kind of connectedness and support from their family! That’s why I thought the book was so powerful! In both its suffering, and in its love.

It is well written as far as keeping you interested (mesmerized actually)! Hilarious one minute, wanting to cry the next. And so eye opening to a side of life we all need to be aware of and have a heart to want to be part of the solution - as complex as it surely is!

I for one am thankful that so many are now curious and are reading the book! Oh… and PS: I had seen the movie, and it doesn’t even come close to having the impact the book does! The movie is dark and depressing… the book is deeply touching and relatable!

Read more

373 people found this helpful

PRNLM

5

An edifying and inspiring, if also troubling at times, read.

Reviewed in the United States on July 25, 2016

Verified Purchase

There is a lot to take in here, even for someone that's seen this life up close in many of its many guises.

While ostensibly about the particular culture of the West Virginia Scots-Irish underclass, anyone that has seen white poverty in America's flyover states will recognize much of what is written about here. It is a life on the very edge of plausibility, without the sense of extra-family community that serves as a stabilizing agent in many first-generation immigrant communities or communities of color. Drugs, crime, jail time, abusive interactions without any knowledge of other forms of interaction, children growing up in a wild mix of stoned mother care, foster care, and care by temporary "boyfriends," and in general, an image of life on the edge of survival where even the heroes are distinctly flawed for lack of knowledge and experience of any other way of living.

This is a story that many of the "upwardly mobile middle class" in the coastal areas, often so quick to judge the lifestyles and politics of "those people" in middle America, has no clue about. I speak from experience as someone that grew up in the heartland but has spent years in often elite circles on either coast.

Two things struck me most about this book.

First, the unflinching yet not judgmental portrayal of the circumstances and of the people involved. It is difficult to write on this subject without either glossing over the ugliness and making warm and fuzzy appeals to idealism and human nature, Hollywood style, or without on the other hand descending into attempts at political persuasion and calls to activism. This book manages to paint the picture, in deeply moving ways, without committing either sin, to my eye.

Second, the author's growing realization, fully present by the end of the work, that while individuals do not have total control over the shapes of their lives, their choices do in fact matter—that even if one can't direct one's life like a film, one does always have the at least the input into life that comes from being free to make choices, every day, and in every situation.

It is this latter point, combined with the general readability and writing skill in evidence here, that earns five stars from me. Despite appearances, I found this to be an inspiring book. I came away feeling empowered and edified, and almost wishing I'd become a Marine in my younger days as the author decided to do—something I've never thought or felt before.

I hate to fall into self-analysis and virtue-signaling behavior in a public review, but in this case I feel compelled to say that the author really did leave with me a renewed motivation to make more of my life every day, to respect and consider the choices that confront me much more carefully, and to seize moments of opportunity with aplomb when they present themselves. Given that a Hillbilly like the author can find his way and make good choices despite the obstacles he's encountered, many readers will find themselves stripped bare and exposed—undeniably ungrateful and just a bit self-absorbed for not making more of the hand we've been dealt every day.

I'm a big fan of edifying reads, and though given the subject matter one might imagine this book to be anything but, in fact this book left me significantly better than it found me in many ways. It also did much to renew my awareness of the differences that define us in this country, and of the many distinct kinds of suffering and heroism that exist.

Well worth your time.

Read more

4 people found this helpful

Jesse Brown

5

Absolutely 5 Stars!

Reviewed in the United States on July 20, 2024

Verified Purchase

No wonder “Hillbilly Elegy” by J.D. Vance is #1 on Amazon’s top purchased books in July 2024, a New York Times Best Seller, and a Netflix movie!!!!!!

(This review does not contain vital spoilers.)

J.D. should be commended for his poignant work, not solely for its exceptional literary quality but for the emotional and informative depth that resonates throughout the narrative. His ability to evoke genuine sentiment is a testament to his storytelling prowess, shocking experiences, and time as a life-long learner. While reading, I had to keep reminding myself that I was reading non-fiction.

His mother was constantly changing up what the “D” in “J.D.” stood for. For me, a humorous moment in the book is when J.D. remarks on his aversion to the name "Donald." When writing this, he had no way of knowing who his future running mate for the United States Presidential Candidacy would be 8 years after this masterpiece was published. That made me laugh out loud.

J.D.'s candid portrayal of his family's struggles offers a stark portrayal of small-town America, urging readers to look beyond initial impressions. I can’t put into words the courage it must have taken him to share the darkest moments and terrible choices of his mother (and other family members) for the world to read about. His courage in revealing personal hardships and familial dynamics underscores the book's authenticity and societal relevance.

J.D.'s exploration of the cyclical nature of poverty, addiction, and fractured families underscores a broader message of resilience and the capacity for change. By drawing parallels between different communities facing systemic challenges, he prompts reflection on shared human experiences and the potential for societal transformation. J.D. proves that we are not facing a race war, but a socioeconomic one right here within our own borders.

J.D. wrote: “Mamaw and Papaw taught me that we live in the best and greatest country on earth. This fact gave meaning to my childhood. Whenever times were tough- when I felt overwhelmed by the drama and the tumult of my youth- I knew that better days were ahead because I lived in a country that allowed me to make the good choices that others hadn’t. (Chapter 11)” That is the sum of this book.

I wholeheartedly recommend “Hillbilly Elegy” to EVERYONE regardless of political affiliations. It serves as a poignant commentary on humanity, the pursuit of the American Dream, and the resilience inherent in the face of adversity. J.D.'s narrative has the power to inspire and provoke thought, leaving a lasting impact on readers. This is an elegy that will stick with me for so many good reasons.

J.D., if you happen to read this review- Thank you for your service in the Marine Corps. Thank you for sharing this highly personal story. Thank you for standing for what is right. And thank you for agreeing to be our next Vice President. Congratulations to your mom on 10 years of sobriety. I’m praying for your family, you, and our country.

Read more

45 people found this helpful

Best sellers

View all

The Tuscan Child

4.2

-

100,022

$8.39

The Thursday Murder Club: A Novel (A Thursday Murder Club Mystery)

4.3

-

155,575

$6.33

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

4.6

-

140,302

$13.49

The Butterfly Garden (The Collector, 1)

4.3

-

88,556

$9.59

Things We Hide from the Light (Knockemout Series, 2)

4.4

-

94,890

$11.66

The Last Thing He Told Me: A Novel

4.3

-

154,085

$2.99

The Perfect Marriage: A Completely Gripping Psychological Suspense

4.3

-

143,196

$9.47

The Coworker

4.1

-

80,003

$13.48

First Lie Wins: A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.3

-

54,062

$14.99

Mile High (Windy City Series Book 1)

4.4

-

59,745

$16.19

Layla

4.2

-

107,613

$8.99

The Locked Door

4.4

-

94,673

$8.53