Angela's Ashes: A Memoir

4.4 out of 5

6,410 global ratings

A Pulitzer Prize–winning, #1 New York Times bestseller, Angela’s Ashes is Frank McCourt’s masterful memoir of his childhood in Ireland.

“When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I managed to survive at all. It was, of course, a miserable childhood: the happy childhood is hardly worth your while. Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood.”

So begins the luminous memoir of Frank McCourt, born in Depression-era Brooklyn to recent Irish immigrants and raised in the slums of Limerick, Ireland. Frank’s mother, Angela, has no money to feed the children since Frank’s father, Malachy, rarely works, and when he does he drinks his wages. Yet Malachy—exasperating, irresponsible, and beguiling—does nurture in Frank an appetite for the one thing he can provide: a story. Frank lives for his father’s tales of Cuchulain, who saved Ireland, and of the Angel on the Seventh Step, who brings his mother babies.

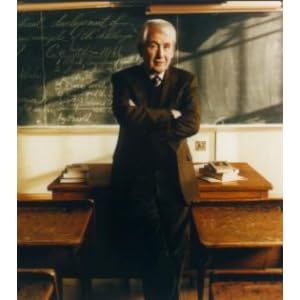

About the authors

Frank McCourt

Frank McCourt (1930-2009) was born in Brooklyn, New York, to Irish immigrant parents, grew up in Limerick, Ireland, and returned to America in 1949. For thirty years he taught in New York City high schools. His first book, "Angela's Ashes," won the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award and the L.A. Times Book Award. In 2006, he won the prestigious Ellis Island Family Heritage Award for Exemplary Service in the Field of the Arts and the United Federation of Teachers John Dewey Award for Excellence in Education.

Read more

Reviews

Fyrecurl

5

A New Literary Classic- an amazing portrayal of real life in the raw

Reviewed in the United States on April 18, 2013

Verified Purchase

The best book I've read this year. If Neil Simon were to have written a novel it may have well looked like this book. A unique voice and style applying humor in all of the right ways for a reader to absorb the sad tragedy of growing up poor, Irish, and Catholic during the depression years, in America, and Ireland. Frank McCourt is able to overcome the pathos of his poignant, sad, and often disturbing memoir of growing up as the oldest son of a poor Irish Catholic family, through use of voice. In Angela’s Ashes, Frank McCourt presents his memoir though the limited first person view of a young boy. He creates comic relief in using the voice of a small child, as he grows up, first in New York, and then in Limerick, Ireland, during the time of the depression, and its aftermath. McCourt presents a tragic account of his family that would generally overwhelm any reader, unless presented through the eyes of a child, who often does not realize the hardship he has undergone, and whose innocent, limited view allows him (and the reader) to keep going. McCourt pushes the reader through the grief of near starvation, the upbringing by an alcoholic father, misguided mother, loss of younger siblings, and the stigma of growing up, poor, Irish, and Catholic, at a time when all three were considered an affliction, like some disease, rather than circumstance. He manages to hold the reader’s interest, without overwhelming her with pathos, by his character’s youthful voice, through artful dialogue, carefully crafted to allow the reader to see the lighter side of his tragic life. His choice of colloquial terms of endearment unique to the Irish of this era, calling his mother “Mam” instead of mom and using “Och” at the start of dialogue summary of the characters who likely had an Irish accent. In the very first paragraph, the author lets the voice of the narrator, pick up the easy ebb and flow of the Irish manner of speaking, and use of the vernacular of an American Irish immigrant, to recall his humble beginnings. “My father and mother should have stayed in New York where they met and married and where I was born. Instead, they returned to Ireland, when I was four, my brother, Malachy, three, the twins, Oliver and Eugene, barely one, and my sister, Margaret, dead and gone.” (McCourt, 11). The reader can almost picture an Irishman speaking as the story begins. McCort introduces comedy into his narrative voice, an older, more mature, man looking back on his life, when he recalls his father: Malachy McCourt, was born on a farm in Toome, County, Antrim. Like his father before, he grew up wild, in trouble with the English, or the Irish, or both. He fought with the Old IRA and for some desperate act he wound up a fugitive with a price on his head. [] When I was a child I would look at my father, the thinning hair, the collapsing teeth, and wonder why anyone would give money for a head like that. (McCourt, 12) This establishes the comic tone of the story through the voice of the character, recalling through his inner thoughts as a child, later through narrative summary, what he was told by his grandmother when he was thirteen; “as a wee lad, your poor father was dropped on his head. It was an accident, he was never the same after, and you must remember that people dropped on their heads can be a bit peculiar.” (McCourt, 12). This revelation becomes more humorous when the reader reconciles it with the story of how the grandmother’s brother, Patrick “Ab” Sheean, became retarded, after his alcoholic father dropped him on his head, when he was a baby. (McCourt, 13). Living with an alcoholic father, even one that is not necessarily abusive, can be a rather difficult subject matter for any reader to plow through, particularly where his alcoholism leave the family so impoverished that his family is near starvation, while he spends what little money on ale however, McCourt’s use of a limited first person view through a child’s eyes, the reader is given an account that is both tolerable, and sometimes funny. Here the voice of the child character portrays the tragic account of life in an impoverished alcoholic family with both catharsis, and humor. He uses word choices indicative of an Irish child, and through creative use of point of view, and method of speaking like a child, he says:

When Dad gets a job Mam is cheerful and she sings, Anyone can see why I wanted your kiss, It had to be and the reason is this Could it be true, that someone like you Could love me, love me?

When Dad brings home the first weeks wages, Mam is delighted, she can pay the lovely Italian man in the grocery shop and she can hold her head up again because there’s nothing worse in the world than to owe and be beholding to anyone. She cleans … she buys … and … on Friday night we know the weekend will be wonderful. … Mam will boil the water on the stove and wash us in the great tin tub and Dad will dry us. Malachy will turn around and show his behind. Dad will pretend to be shocked and we’ll all laugh …(but) when Dad’s job goes into the third week he does not bring home the wages… we know Mam won’t sing anymore one can see why I wanted your kiss. She sits at the kitchen table talking to herself… and Dad rolls up the stairs singing Roddy McCorley. [By the fourth week] Dad loses his job…(McCourt, 23-28). When his new baby sister, Margaret, dies, and his mother shuts down and stares at the wall, the use of a child’s voice enables the reader to somehow cope with the description of neglect of the other small children living in a roach infested apartment, with no food, and having to fend for themselves while their alcoholic father is still out at the pub. Later, when Oliver, one of the twins dies of pneumonia, followed by his brother, Eugene, McCourt’s use of his child’s voice, delivering death of his brothers, and baby sister Margaret into that child’s view that is both tolerable, and hopeful, despite the tears it brings to the reader’s eyes. Malachy and I are back in the bed where Eugene died. I hope he’s not cold in that white coffin in the graveyard though I know he’s not there anymore because angels come to the graveyard and open the coffin and he’s far from the Shannon (River) dampness that kills, up in the sky in heaven with Oliver and Margret where they have plenty of fish and chips and toffee and no aunts to bother you, where all the fathers bring home the money from the Labour Exchange and you don’t have to be running around to pubs to find them. (McCourt, 90). By using comic relief, McCourt is able to keep the reader from being too overwhelmed with pathos for the despair that so many tragic events, death, starvation, alcoholism, poverty and the disdain of insensitive people. He delivers the relief in the familiar family situations that bring smiles, along with the tears. Like when the mischievous brothers climb downstairs when their parents are sleeping and try on the false teeth that sit on the shelf by the sink, and Malachy is unable to remove his father’s big teeth from his mouth and has to go to the hospital. Although a near tragic event, McCourt is able to find the humor in the situation, and relay it to the reader in a believable child’s voice, telling the story. McCort’s portrayal of the family living upstairs in a house where they are unable to live downstairs because of the overwhelming odor from the sewage of many other families which is dumped near their front door, although not funny, is made humorous where the inspectors for the Saint Vincent De Paul Society are told by Malachy, still a child, that his family lives in “Italy” a term they have dubbed the upstairs part of the house where they live. (McCourt, 104). Additionally, when the grandmother stops talking to, and supporting the family, the tragic effect of this fact is reduced when the reason is provided in an anecdote where the main character reveals it was because he puked up God in her backyard after he came home from his first communion, (McCourt, 129), and where he had “God stuck to the roof of (his) mouth.” (McCourt, 128). The reader is compelled to laugh at the thoughts of a child, over a potentially touchy situation that interferes with the grandmother’s faith, and causes a serious rift in the family. Even when the main character’s mother lies dying, and he and his brothers are brought to their aunt’s house, McCourt creates a moment of levity to relive the reader of her heavy heart when he hears his fat aunt in the other room tinkling, and he is afraid to tell his brothers because he thinks they will all break out laughing: “at the picture in our heads of Aunt Aggie’s big white bum perched on a flowery little chamber pot.” (McCourt, 242). Later, when he delivers a message to an Englishman, is dragged into the house, forced to drink sherry and ends up puking on the rose bush belonging to the man’s wife, and is later dismissed from his job, where he is saving to go to America, the reader is spared the severe disappointment by the humor in the story, and a voice that keeps comic relief in everything it describes. (McCourt, 328-329). The book ends on a note of hilarity where the main character, on his way to America, is about to have sex, and a priest comes to his door. “The bad women bring out sandwiches and pour more beer and when we finish eating they put on Frank Sinatra records and ask if anyone would like to dance. No one says yes because you’d never get up and dance with bad women in the presence of a priest …” Despite all of his suffering, McCourt is as entertaining as his is hilarious. He has an enviable voice, Angela’s Ashes is a tribute to any mother’s memory.

McCourt, Frank. Angela’s Ashes. Scribner. New York. 1996.

Read more

14 people found this helpful

Misty Hughes

5

A work of art, and funny to boot!

Reviewed in the United States on November 3, 2015

Verified Purchase

I first read this book years ago when it was first published. I loved it, but it was lost when I lent it to my (formerly) favorite cousin. I was thrilled when it was published as an ebook! The premise of the book is an inspirational tale of overcoming poverty, hardship, and great loss. Set in both New York City and Limerick, Ireland and spanning 20+ years, the story of the McCourt family is both ordinary and extraordinary. The tragedies that befall them will leave you heartbroken at the enormous scope of the losses suffered. It will also leave you infuriated at the foolishness and self-absorption of the parents, who quite honestly are the cause of many of those losses. It was admittedly a different time and a different world than the one most of us know, but the exploitation of their children, both living and dead, to satisfy their own self-destructive vices is appalling. The ability of Mr. McCourt and his brothers to rise above the abject poverty and despair they endured is a true inspiration to anyone who's childhood and raising were less than ideal. His ability to do so with so much humor and grace is a testament to his character and strength. The circumstances he grew up in and the injustices he was subjected to would break many a lesser man. To come from that and not use it as an excuse to follow the same path as his parents, and to not only survive but to thrive in his adult life is proof to us all that we can break the family cycles of abuse and neglect that for many people are all they've ever known. Read this book! It is destined to be one of the great literary classics.

Read more

4 people found this helpful

Cynthia Sally Haggard

5

The many tragedies in his story are leavened by glimpses of humor

Reviewed in the United States on October 7, 2014

Verified Purchase

I don’t think anyone would describe Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, his account of growing up poor and starving in Ireland, as funny. Nevertheless, the many tragedies in his story are leavened by glimpses of humor. Near the beginning of his memoir, McCourt sets the scene in the following way:

Out in the Atlantic Ocean great sheets of rain gathered to drift slowly up the River Shannon and settle forever in Limerick. The rain dampened the city from the Feast of Circumcision to New Year’s Eve. It created a cacophony of hacking coughs, bronchial rattles, asthmatic wheezes, consumptive croaks. It turned noses into fountains, lungs into bacterial sponges…

The rain drove us into the church–our refuge, our strength, our only dry place. At Mass, Benediction, novenas, we huddled in great damp clumps, dozing through priest drone, while steam rose again from our clothes to mingle with the sweetness of incense, flower and candles.

Limerick gained a reputation for piety, but we knew it was only the rain. (1-2)

We learn that it rains in LimerickLimerick, but Limerick is not just wet, it stays wet for eternity. The great sheets of rain drift slowly up the River Shannon and settle forever in Limerick (emphasis added). We learned that the rain dampened the city from the Feast of Circumcision to New Year’s Eve. Not only does the detail of the ‘Feast of Circumcision’ sound humorous, but that sentence actually means that it stayed wet from January 1 to December 31. In the next sentence, McCourt takes things up a notch by providing us with a marvelous list of alliteration and onomatopoeia. Again, the details are compelling. We don’t just have a cacophony of coughs, which sounds clichéd, but a cacophony of hacking coughs. Just when you think this can’t possibly get any worse, McCourt tops that sentence with the next one: “It turned noses into fountains, lungs into bacterial sponges.” After a few more sentences (omitted for brevity), we learn that the rain drove everyone into church, it was “our refuge, our strength, our only dry place.” In this sentence, McCourt gives us a list which acts like a garden path sentence. It implies that it’s talking about one thing (the piety of the people of Limerick), when it’s actually talking about something else (their wish to get out of the rain). The next sentence gives us a marvelous image of all those people crowded into church in “great damp clumps, dozing through priest drone,” and this sets us up for the punch line at the end, that Limerick gained a reputation for piety, but “we knew it was only the rain.”

And so the story begins with some humor, to ease the way for the tragedies that follow. I highly recommend this memoir. Five Stars.

Read more

15 people found this helpful

Enrique A.

5

EXCELENTE

Reviewed in the United States on April 2, 2024

Verified Purchase

EXCELENTE

J. Springer

4

Awesome book!

Reviewed in the United States on November 14, 2017

Verified Purchase

Book review: “Angela’s Ashes” by Frank McCourt...First & foremost, this book taught me that there are levels of poverty. For example, there’s regular poverty, Irish poverty, Irish Catholic poverty, and (worst of all) Irish Catholic poverty in the 1940s. The book is an autobiography on Frank McCourt growing up in Limerick, Ireland. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and, quite frankly, he deserved it...as sad as it is, it is very well written, flows nicely, and keeps the reader wanting more. Some of my favorite highlights from the book:

- “As a child, I thought a balanced diet was bread and tea, a solid and a liquid.” Frank McCourt

- Frank McCourt had beautiful handwriting—a “fine fist” as they said in the old country—and he wrote Angela’s Ashes in longhand.

- I had heard the term Soupers but never knew what it meant: “We had the soupers in the Famine. The Protestants went round telling good Catholics that if they gave up their faith and turned Protestant they’d get more soup than their bellies could hold and, God help us, some Catholics took the soup, and were ever after known as soupers.”

- All this time, I’ve been saying Jesus, Mary, and Joseph! Evidently, I’ve been saying it wrong. Per the book, it’s...Jesus, Mary and Holy St. Joseph!

- Frank’s Mom had a decent sense of humor. Irish Catholic wives were supposed to have children relentlessly. This was her reply after her last baby, Alphie (child #10!): “Mam says, Alphie is enough. I’m worn out. That’s the end of it. No more children. Dad says, The good Catholic woman must perform her wifely duties and submit to her husband or face eternal damnation. Mam says, As long as there are no more children eternal damnation sounds attractive enough to me.” 6.) On your 16th birthday in Ireland, it was tradition to have Your Father take you to the local pub for your first pint Of Guinness (boys only of course)... 7.) The funniest story in the book was when the family was literally cutting the wood walls of their home to use as firewood and were running out!: “Mam says, One more board from that wall, one more and not another one. She says that for two weeks till there’s nothing left but the beam frame. She warns us we are not to touch the beams for they hold up the ceiling and the house itself. Oh, we’d never touch the beams. She goes to see Grandma and it’s so cold in the house I take the hatchet to one of the beams. Malachy cheers me on and Michael claps his hands with excitement. I pull on the beam, the ceiling groans and down on Mam’s bed there’s a shower of plaster, slates, rain. Malachy says, Oh, God, we’ll all be killed, and Michael dances around singing, Frankie broke the house, Frankie broke the house!” 8.) I had never heard the term American Wake but this makes perfect sense: “Mam says we’ll have to have a bit of party the night before I go to America. They used to have parties in the old days when anyone would go to America, which was so far away the parties were called American wakes because the family never expected to see the departing one again in this life.”

Read more

48 people found this helpful

Best Sellers

The Great Alone: A Novel

4.6

-

152,447

$5.49

The Four Winds

4.6

-

156,242

$9.99

Winter Garden

4.6

-

72,838

$7.37

The Nightingale: A Novel

4.7

-

309,637

$8.61

Steve Jobs

4.7

-

24,596

$1.78

Iron Flame (The Empyrean, 2)

4.6

-

164,732

$14.99

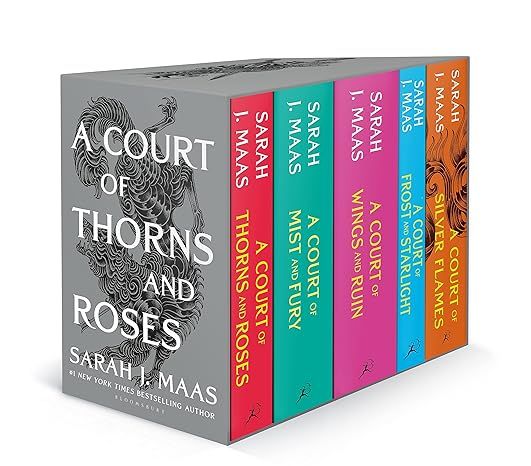

A Court of Thorns and Roses Paperback Box Set (5 books) (A Court of Thorns and Roses, 9)

4.8

-

26,559

$37.99

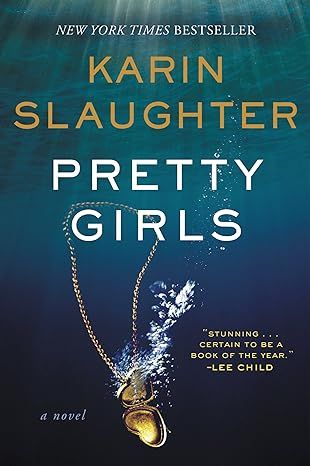

Pretty Girls: A Novel

4.3

-

88,539

$3.67

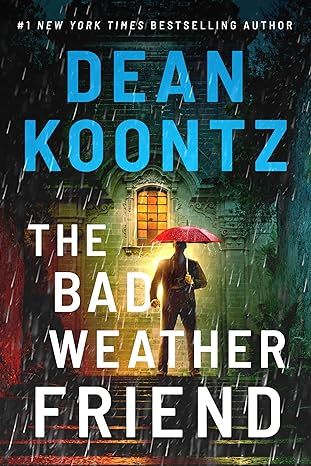

The Bad Weather Friend

4.1

-

34,750

$12.78

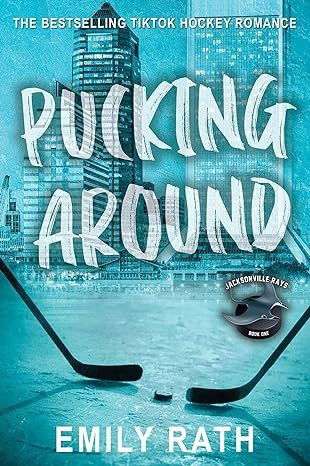

Pucking Around: A Why Choose Hockey Romance (Jacksonville Rays Hockey)

4.3

-

41,599

$14.84

Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action

4.6

-

37,152

$9.99

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow: A novel

4.4

-

95,875

$13.99