The Road to Character

4.3 out of 5

6,393 global ratings

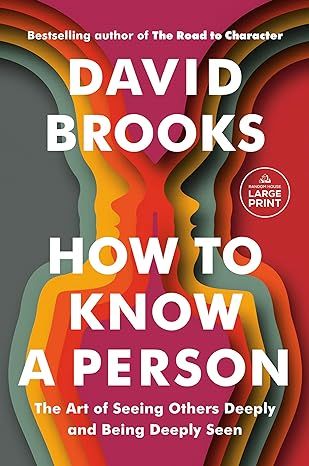

#1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • David Brooks challenges us to rebalance the scales between the focus on external success—“résumé virtues”—and our core principles. NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY THE ECONOMIST With the wisdom, humor, curiosity, and sharp insights that have brought millions of readers to his New York Times column and his previous bestsellers, David Brooks has consistently illuminated our daily lives in surprising and original ways. In The Social Animal, he explored the neuroscience of human connection and how we can flourish together. Now, in The Road to Character, he focuses on the deeper values that should inform our lives.

Looking to some of the world’s greatest thinkers and inspiring leaders, Brooks explores how, through internal struggle and a sense of their own limitations, they have built a strong inner character. Labor activist Frances Perkins understood the need to suppress parts of herself so that she could be an instrument in a larger cause. Dwight Eisenhower organized his life not around impulsive self-expression but considered self-restraint. Dorothy Day, a devout Catholic convert and champion of the poor, learned as a young woman the vocabulary of simplicity and surrender. Civil rights pioneers A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin learned reticence and the logic of self-discipline, the need to distrust oneself even while waging a noble crusade.

Blending psychology, politics, spirituality, and confessional, The Road to Character provides an opportunity for us to rethink our priorities, and strive to build rich inner lives marked by humility and moral depth.

“Joy,” David Brooks writes, “is a byproduct experienced by people who are aiming for something else. But it comes.”

Praise for The Road to Character

“A hyper-readable, lucid, often richly detailed human story.”— The New York Times Book Review

“This profound and eloquent book is written with moral urgency and philosophical elegance.”—Andrew Solomon, author of Far from the Tree and The Noonday Demon

“A powerful, haunting book that works its way beneath your skin.”**—The Guardian

“Original and eye-opening . . . Brooks is a normative version of Malcolm Gladwell, culling from a wide array of scientists and thinkers to weave an idea bigger than the sum of its parts.”—** USA Today

320 pages,

Kindle

Audiobook

Hardcover

Paperback

Audio CD

First published September 12, 2016

ISBN 9780812983418

About the authors

David Brooks

David Brooks is an op-ed columnist for The New York Times and appears regularly on “PBS NewsHour,” NPR’s “All Things Considered” and NBC’s “Meet the Press.” He teaches at Yale University and is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He is the bestselling author of The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement; Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There; and On Paradise Drive: How We Live Now (And Always Have) in the Future Tense. He has three children and lives in Maryland.

Read more

Reviews

Jane in Milwaukee

5

I've been hungering for this book and I didn't even know it

Reviewed in the United States on April 17, 2015

Verified Purchase

The other night on PBS I saw Charlie Rose interview David Brooks about this book. Almost before it was over, I raced to Amazon and clicked "order now." Boy am I glad I saw that program.

This book focuses on "résumé virtues" vs. "eulogy virtues." While we ask a stranger at a bar, "what do you do?"...Brooks would like us to ask ourselves "what is my character?" In indepth study, he zeroed in on Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik's terms Adam I and Adam II as the allegory to describe the two conflicting parts of humans. Adam I is "externally oriented" being career driven and ambitious; Adam II is focused internally on his values and moral quality. Just as JFK said, "Ask not what your country can do for; ask what you can do for your country"; Brooks concludes that Adam I wants to conquer the world while Adam II wants to obey a calling to serve the world.

Through a great introduction and then a series of essays of great people, Mr. Brooks leads us through his journey toward developing his best character: moving toward love, humility, joy, a greater purpose, passion. The essays include the lives of Eisenhower (actually, his mother Ida), George Marshall, George Eliot, Augustine and Samuel Johnson--what a panoply of people! No mention of a pope or Mother Teresa, Gandhi or Martin Luther King, Jr. But flowing through considerations that some of these greats wrestled with.

I kept reading a few pages and then setting the book down to contemplate it, quite unusual for me. I guess this books speaks to something deep inside that I didn't have a vocabulary for before. What is character? What are our morals and how did we develop them...or did they develop us? These profound questions are answered from different angles via a discussion of social history and these and other individuals' lives which often flew in the face of society.

For example, in the interview with Charlie Rose, Brooks floored him when he asked what Rose thought Eisenhower's greatest challenge was: his terrible temper. After a long discussion about Ike's courageous mother, Brooks explains in the book the line from the Bible she quoted probably set him on the course toward general and president: "He that conquereth his own soul is greater than he who taketh a city." George Marshall provides an interesting comparison to Eisenhower. When FDR was looking for the man to lead Operation Overlord, the retaking of France, his first choice was Marshall. When Marshall found himself summoned to the Oval Office, FDR offered him the job. Marshall desperately wanted the position but he hemmed and hawed and said whatever the President thought best. Marshall was passed over for Eisenhower. Marshall didn't put "self" first but whatever was seen as best for the country.

Brooks says that if people only realized our nature is steered toward love instead of power and material things, we'd be a lot happier. But reaching joy also means you have to be willing to confront your own flaws and sins and to work on them constantly. These are a few of his ultimate conclusions: --We don't live for happiness...we live for holiness. --We are famously flawed but also splendidly endowed. --In the struggle against your own weakness, humility is your great virtue and pride is the greatest vice. --Character is built from your constant inner confrontation. --The vices that lead us astray--the 7 Deadly Sins--are temporary; the elements of our character are long-lived. --We can't do it ourselves...we need redemption. Jesus said we're all sinners--who am I to argue?

This book doesn't lend itself well to superficial skimming. If you're going to get something out of it, take your time. You may not agree with all the assumptions and tenets but, by gum, it's going to get you thinking.

Read more

83 people found this helpful

Brian Johnson | Heroic

5

It’s a deeply inspiring read and I highly recommend it.

Reviewed in the United States on May 16, 2016

Verified Purchase

“We live in a society that encourages us to think about how to have a great career but leaves many of us inarticulate about how to cultivate the inner life. The competition to succeed and win admiration is so fierce that it becomes all-consuming. The consumer marketplace encourages us to live by a utilitarian calculus, to satisfy our desires and lose sight of the moral stakes involved in everyday decisions. The noise of fast and shallow communications makes it harder to hear the quieter sounds that emanate from the depths. We live in a culture that teaches us to promote and advertise ourselves and to master the skills required for success, but that gives little encouragement to humility, sympathy, and honest self-confrontation, which are necessary for building character.

This is a book about ... how some people have cultivated strong character. It’s about one mindset that people through the centuries have adopted to put iron in their core and to cultivate a wise heart. I wrote it, to be honest, to save my own soul. ...

I wrote this book not sure I could follow the road to character, but I wanted at least to know what the road looks like and how others have trodden it.”

~ David Brooks from The Road to Character

In today’s world, the road to character has a much less defined map than the road to external success.

In this thoughtful, penetrating book, New York Times op-ed columnist and author David Brooks walks us through the evolution of our culture away from a character ethic toward a society all about what he calls the “Big Me.”

And, of course, he shows us the way back to character.

David is explicit that the book isn’t a “7 point program” to build your character. Rather he shares stories of moral exemplars (ranging from Dwight Eisenhower and George Marshall to Frances Perkins and Dorothy Day) to inspire us to be a little better today than we were yesterday.

Let's take a quick look at some of my favorite Big Ideas:

- Resume Virtues - vs. Eulogy virtues.

- What Is Character? - And how do you get it?

- The Summons - What does life want from you?

- Conquer Yourself - That's step 2.

- Don't Live for Happiness - Live for Holiness.

Let’s join (and help create!) the counterculture of virtue.

From my soul to yours, I’m sending love and gratitude as we take the next steps on our roads to character.

More goodness— including PhilosophersNotes on 300+ books in our OPTIMIZE membership program. Find out more at brianjohnson . me.

Read more

29 people found this helpful

David Fretes

5

Recommended.

Reviewed in the United States on September 22, 2024

Verified Purchase

Amazing book, to keep growing in ourselves.

Jerry Woolpy

5

A Review by Jerry Woolpy of David Brooks’, The Road to Character

Reviewed in the United States on May 11, 2015

Verified Purchase

A Review by Jerry Woolpy of David Brooks’, The Road to Character

What do Frances Perkins, Dwight Eisenhower, Dorothy Day, George Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, Mary Anne Evans (George Eliot), Augustine, and Samuel Johnson have in common? They are the various lives that David Brooks sketches as examples of a wide range of people of character. Brooks thinks that since the end of WWII, somewhere between Johnny Unitas and Joe Namath, our society became more directed toward merit and talent and less direct toward character, truth, and love. Self-esteem preempted humility. Rather than disciplining our children we “friended” them. “The realist tradition that emphasized limitation and moral struggle was inadvertently marginalized and left by the side of the road, first by the romantic flowering of positive psychology, then by the self-branding ethos of social media, finally by the competitive pressures of the meritocracy” (pp253-254). Through the examples Brooks preaches holiness above happiness, overcoming selfishness and overconfidence, recognizing our sins and correcting them, acknowledging our weaknesses with humility, acknowledging that pride is our central vice and that the struggle against sin and for virtue is the central drama of life; character is a set of dispositions, desires, and habits that are slowly engraved during the struggle against your own weakness; in the short term— lust, fear, vanity, gluttony lead us astray but character can rescue us over the long term with courage, honesty, and humility; everybody needs redemptive assistance from God, family, friends, ancestors, rules, traditions, institutions, and exemplars; the struggle against weakness often has a U shape--you are living your life and then you get knocked off course; only by quieting the self, by muting the sound of your own ego, can you see the world clearly; we are generally not capable of understanding the complex web of causes that drive events; the best leaders try to lead along the grain of human nature rather than against it; maturity is earned not by being better than other people at something, but by being better than you used to be, by being dependable in times of testing and straight in times of temptation. Some are bound to say the book is “retro” but if you are open to it, The Road to Character is a fine critique of our society.

Read more

2 people found this helpful

Thomas M. Loarie

5

A Most Challenging Book to Review: Being Envied or Admired in Today’s Selfie Culture?

Reviewed in the United States on October 4, 2015

Verified Purchase

Writing an adequate review for best-selling author David Brook’s “The Road to Character” has been challenging. I typically work with five pages of detailed notes when reviewing a book but found myself with twenty-one pages for this review.

Brooks has written a gem of a book, one that raises the bar for future discussions of “character”. It takes time to absorb and savor. Brooks says publicly that he wrote this book to save his own soul.

“The Road to Character” is about the cultural shift from the “little me” to the “BIG ME,” from a culture that encourages people to think humbly of themselves to a culture that encourages people to see themselves as the center of the universe. This cultural shift encourages us to think about having a great career but leaves nothing for us to develop an inner life and character. For Brooks, we have lost our way to “being good” and “doing good.”

Brooks frames the discussion by contrasting “resume virtues” - those skills that one brings to the job market that contribute to external success – with “eulogy virtues” – those that are at the core of our being like courage, honesty, loyalty, and the quality of our relationships that contribute to real joy. These are embodied in two competing parts, Adam I and Adam II, of our nature that are a constant source of contradiction and tension.

Adam I is the external Adam. He wants to build, create, produce and discover things. He is characterized by actively seeking recognition, satisfying his desires, being impervious to the moral stakes involved. He has little regard for humility, sympathy, and honest self-confrontation, which are necessary for building character. He wants to have high status, win victories, and conquer the world.

Adam II is the internal Adam. He wants to embody certain moral qualities. He wants to love intimately, to sacrifice self in the service of others, to live in obedience to some transcendent truth, and to have a cohesive inner soul that honors creation in one’s own possibilities. Adam II is charity, love, and redemption.

Adam I is at work in today’s “BIG ME” culture. “Big Me” messages are everywhere; you are special; trust yourself; and be true to yourself. This ‘Gospel of Self’ begins with childhood when awards and rewards are given for just being, not doing. “We are all wonderful, follow your passion, don’t accept limits and chart your own course.”

This has led to an ethos based on a “ravenous hunger in a small space of self-concern, competition, and a hunger for distinction at any cost,” an ethos where envy has replaced admiration. This self-centeredness leads to several unfortunate directions: selfishness, the use of other people as a means to an end, seeing oneself as superior to everyone else, and living with a capacity to ignore and rationalize one’s imperfections and inflate one’s virtues.

The “BIG ME” culture distorts the purpose of our journey and the meaning of life. “Parts of themselves go unexplored and unstructured. They have a vague anxiety that their life has not achieved its ultimate meaning and significance. They live with unconscious boredom, not really loving, and unattached to the moral purpose that gives life it’s worth. They lack the internal criteria to make unshakable commitments. They never develop inner constancy, the integrity that can withstand popular disapproval or a serious blow. They foolishly judge others by their abilities and not by their worth. This external life will eventually fall to pieces.”

In this increasingly “BIG ME” culture, Brooks became haunted by the voices of the past and the quality of humility and character they exhibited. People in the past guarded themselves against some of their least attractive tendencies to be prideful, self-congratulatory, and hubristic. “You would not even notice these people. They were reserved. They did not need to prove anything in the world.” They embodied humility, restraint, reticence, temperance, respect, and soft discipline. “They radiated a sort of moral joy. They answered softly when challenged harshly. They were silent when unfairly abused, dignified when others tried to humiliate them, and restrained when others tried to provoke them…

But they got things done. They were not thinking about what impressive work they were doing. They were not thinking about themselves at all. They just seemed delighted by the flawed people around them. They made you feel funnier and smarter when you spoke with them. They moved through all social classes with ease. They did not boast. They did not lead lives of conflict-free tranquility but struggled towards maturity. These people built a strong inner character, people who achieved a certain depth. They surrendered to the struggle to deepen their soul.”

Brooks highlights the lives of prominent and influential people - Francis Perkins, Dwight Eisenhower, Dorothy Day, George C. Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, George Eliot, St. Augustine, Samuel Johnson, Michel de Montaigne – to articulate the diverse roads taken by a diverse set of people, white and black, male and female, religious and secular, literary and non-literary. Not one of them was even close to perfect. They were acutely aware of their own weaknesses and they waged an internal struggle against their sins to emerge with some measure of self-respect..

“The Road to Character” is a “road less traveled.” It involves moments of moral crisis, confrontation, and recovery. To go up, one first has to go down (The “U Curve”); one must descend into the valley of humility to climb to the heights of character. Only then will one have the ability to see their own nature, their everyday self-deceptions, and shatter all Illusions of self-mastery.

Humility is central to the journey. Humility leads to wisdom, a moral quality of knowing what you don’t know and finding a way to manage ignorance, uncertainty, and limitation. It offers freedom…freedom from the need to prove your superiority. Alice had to be small to enter Wonderland. “Only the one who descends into the underworld rescues the beloved.”

The paradox for Adam I is that he cannot achieve enduring external success unless he builds a solid moral core as sought by Adam II. Without inner integrity, your Watergate, your scandal, your betrayal, will eventually happen. Adam I versus Adam II, Adam I ultimately depends on Adam II.

Brooks wrote this book to learn who has traveled this road to character, and what it looks like. He found you cannot be the good person you want to be unless you wage this campaign against self. I highly recommend this book as one of the most profound books published this year.

End note: Brook’s sections on love and suffering are excellent.

Read more

275 people found this helpful

Eli P. Cox III

5

especially when some dismiss positive virtues as being unnecessary or harmful to society

Reviewed in the United States on December 3, 2016

Verified Purchase

The Road to Character by David Brooks and The Power of Ideals: The Real Story of Moral Choice by William Damon and Anne Colby are complementary books dealing with the unfortunate state of positive ethics in America. The distinction between positive and negative ethics is illustrated by the Ten Commandments where positive ethics are constituted of commands to take action (you shall honor your parents) while negative ethics are constituted of commands to refrain from action (you shall not steal). Both are important, but positive ethical acts such as treating others with civility, voting, working at polling stations, serving in the military, supporting charities, promoting social causes, and lending a hand to strangers are distinctive aspects of American character.

Road to Character, published by Random House, targets the prevalence of narcissism, “the big me,” that marginalizes others. Power of Ideals, published by Oxford University Press, is written in opposition to the new science of morality that debases ethical behavior and fails to account for the extraordinary moral courage of the exemplars described in these two books. Both promote moral ideals and both are quite readable.

Road to Character presents five moral exemplars, some of whom have obvious shortcomings, and a host of supporting examples while Power of Ideals describes another six. David Brooks, William Damon, and Anne Colby are themselves moral exemplars by performing the important public service of writing these books, especially when some dismiss positive virtues as being unnecessary or harmful to society.

In ratings on Amazon.com, Road to Character has received 4.2 out of 5.0 stars while Power of Ideals has received 5.0 out of 5.0. The first book has received 1,312 reviews, including mine, while the second has received only six. Both are excellent and are recommended to all concerned about the deterioration of the values that have made our nation great.

Read more

J. M. Alexander

4

A Relevant Look at Modern Morality

Reviewed in the United States on February 16, 2016

Verified Purchase

This is very introspective book, one that the author says he wrote “to save his own soul”. He first discusses what he refers to as our “resume virtues” and our “eulogy virtues”. The resume virtues are the skills that you bring to the job market and that contribute to external success. He describes the eulogy virtues as the ones that are talked about at your funeral, the deeper virtues that exist at the core of your being- whether you are kind, brave, honest or faithful; what kind of relationships you formed. The book seeks to identify and hopefully attain these latter virtues on one’s way to achieving character. He uses another analogy in speaking to these virtues, describing the first as typical of “Adam I”, while the others are labeled as being sought by “Adam II”. I see this distinction as one between the search for recognition from others (Adam I) and the realization that the important recognition comes from within and reflects a moral adherence to some transcendent truth, sacrifice in the service of others, an inner identity that honors the wonders of creations and one’s own possibilities, and the ability to experience intimate love (Adam II). The author feels that to nurture your Adam I career, it makes sense to cultivate your strengths. To nurture your Adam II moral core, it is necessary to confront your weaknesses. The author seemed inspired by listening to a public radio rebroadcast of a show that immediately aired after WWII. It was hosted by well known celebrities who set a tone of self-effacement and humility. The Allies had just completed one of the noblest military victories in human history. And yet there was no chest beating. Nobody was erecting triumphal arches. He noted how this tone of thankfulness and humility, with the absence of bravado, was in such contrast to the self aggrandizing “celebrations” we see regularly at sports events. He wonders at what has produced such change, and whether we have lost the sense of character that was present so many years ago. The author then examines present attitudes, and the contrast with those of the past. He does not suggest a return to the “good old days”, or even characterize such times as such, but just seeks out the changes in, and causes of, the current moral climate. His research suggests that our country has seen a broad shift from a culture of humility to the culture of what he calls the “Big Me”, from a culture that encouraged people to think humbly of themselves to a culture that now encourages people to see themselves as the center of the universe. To support this idea of the “Big Me”, the author notes surveys of the attitudes of young people over the last almost 50 years. In 1966 80 percent of incoming college freshmen said they were strongly motivated to develop a meaningful philosophy of life. Today that figure is less than half. In 1966 42 percent said becoming rich was an important life goal, in 1990 the number was 74 percent. In a 1976 survey that asked people to list their life goals, fame ranked fifteenth out of sixteen. By 2007, 51 percent of young people reported that being famous was one of their top personal goals. And this self centeredness has been accompanied by a certain indulgence from society as a whole, an unwillingness to be critical, but instead focus on supporting self esteem, perhaps at the loss of character. As an example, the author notes that in 1966, only about 19 percent of high school students graduated with an A or A– average. By 2013, 53 percent of students graduated with that average, according to UCLA surveys of incoming college freshmen. These changing attitudes highlight the stark contrast from the culture of humility mentioned above. The author also refers to this as the “crooked timber” school of humanity. People who ascribe to it have an acute awareness of their own flaws and a belief that character is built in the struggle against their own weaknesses. They must wage this campaign through effort and artistry, through the self discipline to adhere to external standards. But character is not built through self discipline alone, but also constructed sweetly through love and pleasure. When you have deep friendships with good people, you copy and then absorb some of their best traits. When you love a person deeply, you want to serve them and earn their regard. When you experience great art, you widen your repertoire of emotions. This journey to character is not a solitary experience. Individual will, reason, compassion, and character are not strong enough to consistently defeat selfishness, pride, greed, and self-deception. Everybody needs redemptive assistance from outside—from family, friends, ancestors, rules, traditions, institutions, exemplars, and, for believers, God. The author also feels, as do many others, that one must endure some suffering, some loss of control, a “falling”, in order to then climb to the heights of character. Such event need not be a sudden epiphany, it can also happen in a daily, gradual way. At some point one must find his or her “calling” or vocation, a devotion to something larger than himself or herself. But how did this change in attitude come about? The author traces it back to philosophical differences in the 18th century, contrasting moral realism with moral romanticism. While moral realists placed emphasis on inner weakness, moral romantics placed emphasis on our inner goodness. The realists believed in cultivation, civilization, and artifice; the romanticists believed in nature, the individual, and sincerity. The author observed that realism reigned supreme in America during the first part of the twentieth century, but then began to wane. One would assume that this cultural change occurred in the 60's and 70's- a time of general dissatisfaction among many of our youth. But Mr. Brooks traces it instead to the prior “Greatest Generation”. These were the people who had endured 16 years of deprivation during the Great Depression and WWII, and were ready to let loose and enjoy life. Consumerism was rampant as people sought to escape the shackles of self-restraint and all those gloomy subjects like sin and depravity. Self help books abounded and it was argued that the primary psychological problem was that people didn’t love themselves enough. The focus shifted from the flawed view of human nature to an emphasis on pride and self esteem. Some philosophers called this “the culture of authenticity,” a mindset based on the romantic idea that each of us has a Golden Figure in the core of our self, an innately good True Self, which can be trusted, consulted, and gotten in touch with. Moral authority is no longer found in some external objective good, but rather in each person’s unique original self. In this ethos, sin is not found in your individual self; it is found in the external structures of society—in racism, inequality, and oppression. To improve yourself, you have to be taught to love yourself, to be true to yourself, not to doubt yourself and struggle against yourself. Although the author acknowledges that this new sense of self-esteem gave women, and other groups, the language to articulate and cultivate self-assertion, strength and identity; it also began an acceptance of the “Big Me” sense of morality. This has been exacerbated by the omnipresence of social media which has made communication faster and busier, has diminished periods of silence and reflection, and encourages what the author calls a “broadcasting personality”. The social media maven spends his or her time creating a self-caricature, a much happier and more photogenic version of real life. People subtly start comparing themselves to other people’s highlight reels, and of course they feel inferior. People seeks false “friends”on Facebook or other social media, and seem to be constantly “selling” themselves to others, either socially or in the workplace. It’s a culture in which people are defined by their external abilities and achievements, in which a cult of busyness develops as everybody frantically tells each other how over committed they are. At least to this reader there seems a certain irony in the fact that this “Big Me” morality, focusing more inward, is caught in an endless and relentless attempt to find approval from others. So the author finds that the ego driven “Adam I” has overshadowed the humble “Adam II”. He then notes that to restore the balance, to rediscover Adam II, to cultivate the eulogy virtues, it is necessary to revive and follow what we accidentally left behind: the counter-tradition of moral realism, or what he has called the “crooked-timber” school. We must build a moral ecology based on the ideas of this school, to follow its answers to the most important questions: Toward what should I orient my life? Who am I and what is my nature? How do I mold my nature to make it gradually better day by day? What virtues are the most important to cultivate and what weaknesses should I fear the most? How can I raise my children with a true sense of who they are and a practical set of ideas about how to travel the long road to character. He suggests a number of guideposts for this journey. We must recognize that we our lives are not just the pursuit of pleasure, but of purpose, righteousness and virtue. Life is essentially a moral drama, not a hedonistic one. We must realize that we are flawed creatures, but still splendidly endowed. We are both weak and strong, bound and free, blind and far seeing and have the capacity to struggle within ourselves, potentially sacrificing worldly success for the sake of an inner victory. In this struggle, humility is our greatest virtue. It is the ability to accurately assess our nature and place in the universe; to be aware of our own weakness, to know that we are not the center of the universe but serve something higher. Pride is the central vice that blinds us from our divided nature, that misleads us into thinking that we are greater than we are. It makes coldheartedness more possible and love less so. We must know that once the necessities of survival are satisfied, the struggle against sin and for virtue should be life’s central drama. And we must realize that the most essential parts of life are matters of individual responsibility and moral choice: whether to be brave or cowardly, honest or deceitful, compassionate or callous, faithful or disloyal. Character is built in the course of this inner struggle by developing dispositions, desires, and habits that are slowly engraved against our own weakness. If one makes disciplined, caring choices, such action slowly engraves certain tendencies in the mind, tendencies that will lead to the desire to continue to do the right thing and make the right choices. The things that lead us astray on this journey are short term—lust, fear, vanity, gluttony. The things we call character endure over the long term—courage, honesty, humility. And this is not a journey that we can successfully travel alone. Everyone needs redemptive assistance from outside- from God, family, friends, ancestors, rules, traditions, institutions, and exemplars. We need some external guidance that can be trusted. We must quiet our own self, muting the sound of our ego so that we can see the world clearly and realize that we are an accepted member of this mystical universe, that, in religious terms, we have received grace. We must cultivate modesty in order to gain wisdom. To be wise we must know that we do not, nor can not understand all of the mysteries we encounter. We must seek out a calling or a vocation that requires us to seek out something greater than ourselves. We must realize that our struggle against weakness and sin may not make us rich or famous, but will render us more mature, joyful and content. And perhaps most importantly, we must know that this is not a struggle that we can win, but one that we must be engaged in. The author might best capsulize the importance of the road to character by his reference to joy: “There’s joy in a life filled with interdependence with others, in a life filled with gratitude, reverence, and admiration. There’s joy in freely chosen obedience to people, ideas, and commitments greater than oneself. There’s joy in that feeling of acceptance, the knowledge that though you don’t deserve their love, others do love you; they have admitted you into their lives. There’s an aesthetic joy we feel in morally good action, which makes all other joys seem paltry and easy to forsake.” Although I think this summary captures the basic message of the book, it by no means covers all its content. Most of the length of the book is devoted to the biographical sketches of historical figures, some very familiar and some less well known, who exhibited great character in their lives. The author uses them as examples of the different paths to character, and the experiences that prompted these individuals to ascribe to something higher than themselves. Dwight Eisenhower and George Marshall found service to their country a life’s calling, and that the honor and discipline of the military offered the best framework in which such service could be fulfilled with character. Frances Perkins was a social activist in the early decades of the 20th century, but her sense of service was galvanized by the horrible tragedy of the Triangle fire in New York. Dorothy Day was so struck by the miracle of the birth of her child that she turned wholeheartedly to work in the Catholic church, immersing herself in service to the disadvantaged. Samuel Johnson, a man plagued by many physical maladies, found his salvation and his calling in his writing. He would not abide any dishonesty and sought to produce accurate and intellectually honest work. A. Philip Randolph, a great civil rights leader, showed his character through a devotion to education, his incorruptibility, and his unflinching sense of dignity. Mary Anne Evans, the 19th century English writer who went by the pen name George Eliot, found her sense of self and her path to character through the total and unconditional love of her husband. These and other of the author’s examples were flawed individuals, but exhibited great character in battling their flaws. They took different “roads to character”- some secular, some religious, some more personal- clearly demonstrating the different paths that can be successful. All found something bigger than themselves to devote themselves to, and through which they gained their own measure of grace. I think Mr. Brooks has produced a thoughtful and thought provoking work of great relevance to today’s society. It is well written, although at times the biographical pieces are not as pointed as I might have felt necessary. However, I did enjoy them and found the stories to be some of the useful “exemplars” that the author feels are necessary. I also thought they were instructive because of the failings of these individuals who did, in most settings, display great character. This is a book that is a fairly easy and enjoyable read, and well worth the effort.

Read more

57 people found this helpful

Michael J. Kerrigan

4

Adam I Surrenders to Adam II

Reviewed in the United States on November 7, 2015

Verified Purchase

David Brooks, The Road to Character, in my view, ranks four stars but more important than my ranking, Brooks book profoundly influenced my thinking of my past and present life. First let me explain the ranking then how the book impacted my thinking.

His book takes on not only an important discussion of character but also the challenging topic of sin, redemption and the inner life. It is well crafted, beginning with the distinction between resume virtues (Adam I) and eulogy virtues (Adam II) and concludes with an excellent summation of the “humility code.”

At the outset and throughout this well written book, Brooks explains a vocation is not a career but a calling. Like Plutarch and other moralists, Brooks describes the lives of individuals with inner greatness, such as Frances Perkins, Dwight Eisenhower, George Marshall, A. Philip Randolph and Saint Augustine. Chapter 8 on Ordered Love offers a superb explanation of Saint Augustine’s journey, initially building happiness around his considerable career accomplishments (Adam I) to later answering his calling (vocation) by eventually submitting to the will of God. The book is well worth the price if only by reading the introduction, chapter 8 and the final chapter describing the humility code. However, I was disappointed with the obligatory genuflection to political correctness, given my reading, of the chapters on Mary Anne Evans and Dorothy Day.

Now for my own reflection on how Brooks explanation of resume virtues accurately typed my own pre-vocation career. My occupation as a paid advocate (lobbyists) was cut short by illness. My career strategy was based on Adam I thinking, that is, on how to succeed in the meritocracy. I admit my favorite poem was William Ernest Henley’s, “Invictus”: I am the master of my fate/I am the captain of my soul. My favorite song was Sinatra’s I Did It My Way and my favorite books were the self-help books from Norman Vincent Peale’s, The Power of Positive Thinking to Stephen Covey’s: 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. In reading Brooks I felt rightly and showily cast as the archetypal Adam I.

Ironically, as my professional career ended prematurely, my character-building calling allowed me to reflect outside myself and offered the time to study how character is built. I now have the luxury to delve deeper on the ethic of self-sacrifice and study people, who through their moral choices, have formed a strong inner character. More and more I realize how little control I have had or can have over my life; more and more I have come to realize I cannot earn nor merit my way into heaven. The more I understand this reality, the more I have come to understand I must surrender my will to God’s.

Thank you David Brook for writing the Road to Character, especially for your excellent explanation of the Ordered Love of Saint Augustine.

Read more

9 people found this helpful

Bijan Davari

4

Good reading

Reviewed in the United States on June 20, 2024

Verified Purchase

We are reading this book in our book-reading group. It is a good review of the life story of important people in our country, who each had significant effects on the events or the processes that happened in recent history. It focuses on the character of each of these people and how they developed during their respective lives. However, it goes into more details of these characters, and includes repetition on each person's character / feature. I recommend reading it, with the latter reservation.

Read more

Nelda

3

Enjoyable Read

Reviewed in the United States on February 16, 2024

Verified Purchase

The Road to Character, by David Brooks, is a well-researched book as seen in his detailed presentation of different people throughout history. Each found strength of character despite weaknesses or tragic circumstances. Sometimes the research was overwhelming and details or explanations of love, reticence, etc., seemed to go on much too long, longer than the concrete examples of George Marshall, Dwight Eisenhower, Dorothy Day, Samuel Johnson, Michel de Montaigne, and others. Some might quibble that Marshall did not make a mistake about the creation of the state of Israel (while wonderful to have their own state, this state brought on the problems he predicted). I would certainly quibble with the author in bringing up the coolness and dismissiveness of Eishenhower’s note to his mistress. I didn’t understand why his wife Mamie wasn’t mentioned as well. Wasn’t his worst sin cheating on his wife? If I had been Mamie, there would have been more than a cool and dismissive letter to deal with. In a moving and, of course, well-researched assessment, Brooks compares the character building of days gone by with its current replacement: the more external pursuits of wealth and achievement. The last chapter put all the chapters’ ideas in one summary list called the Humility Code. This 15-item list indeed simplifies the book’s ideas, not a bad thing at all. An example of one of the gems in this list is his discussion of maturity: “The person who successfully struggles against weakness and sin may or may not become rich and famous, but that person will become mature. Maturity…is not comparative…. It is earned not by being better than other people at something, but by being better than you used to be.” This book, too, might make you "better than you used to be,” but it is not always an easy book to read because of its tedious and slow build-up to his overall message. However, I guess patience with the text and a thoughtful reflection throughout might be other ways to build one’s character! --from my Goodreads review

Read more

Top David Brooks titles

Best Sellers

The Tuscan Child

4.2

-

100,022

$8.39

The Thursday Murder Club: A Novel (A Thursday Murder Club Mystery)

4.3

-

155,575

$6.33

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

4.6

-

140,302

$13.49

The Butterfly Garden (The Collector, 1)

4.3

-

88,556

$9.59

Things We Hide from the Light (Knockemout Series, 2)

4.4

-

94,890

$11.66

The Last Thing He Told Me: A Novel

4.3

-

154,085

$2.99

The Perfect Marriage: A Completely Gripping Psychological Suspense

4.3

-

143,196

$9.47

The Coworker

4.1

-

80,003

$13.48

First Lie Wins: A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.3

-

54,062

$14.99

Mile High (Windy City Series Book 1)

4.4

-

59,745

$16.19

Layla

4.2

-

107,613

$8.99

The Locked Door

4.4

-

94,673

$8.53