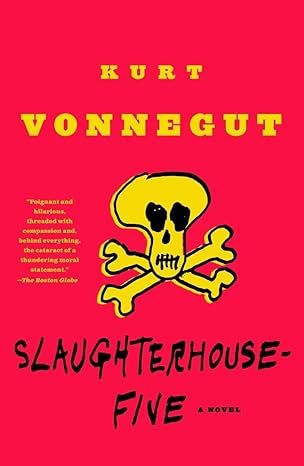

Slaughterhouse-Five: A Novel (Modern Library 100 Best Novels)

4.4

-

34,268 ratings

Slaughterhouse-Five, an American classic, is one of the world’s great antiwar books. Centering on the infamous firebombing of Dresden, Billy Pilgrim’s odyssey through time reflects the mythic journey of our own fractured lives as we search for meaning in what we fear most.

Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death is a 1969 semi-autobiographic science fiction-infused anti-war novel by Kurt Vonnegut. It follows the life experiences of Billy Pilgrim, from his early years, to his time as an American soldier and chaplain's assistant during World War II, to the post-war years. Throughout the novel, Billy frequently travels back and forth through time. The protagonist deals with a temporal crisis as a result of his post-war psychological trauma. The text centers on Billy's capture by the German Army and his survival of the Allied firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, an experience that Vonnegut endured as an American serviceman. The work has been called an example of "unmatched moral clarity" and "one of the most enduring anti-war novels of all time".

Kindle

$9.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$16.19

Paperback

$14.86

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

0385333846

ISBN-13

978-0385333849

Print length

288 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Dial Press Trade Paperback

Publication date

January 11, 1999

Dimensions

5.23 x 0.55 x 7.99 inches

Item weight

2.31 pounds

Popular highlights in this book

All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist.

Highlighted by 5,575 Kindle readers

Like so many Americans, she was trying to construct a life that made sense from things she found in gift shops.

Highlighted by 5,392 Kindle readers

“Well, here we are, Mr. Pilgrim, trapped in the amber of this moment. There is no why.”

Highlighted by 3,583 Kindle readers

And I asked myself about the present: how wide it was, how deep it was, how much was mine to keep.

Highlighted by 3,316 Kindle readers

Product details

ASIN :

B000SEGHT6

File size :

2520 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Editorial reviews

“Poignant and hilarious, threaded with compassion and, behind everything, the cataract of a thundering moral statement.”—The Boston Globe

“Very tough and very funny . . . sad and delightful . . . very Vonnegut.”—The New York Times

“Splendid . . . a funny book at which you are not permitted to laugh, a sad book without tears.”—Life

“Funny, satirical, compelling, outrageous, fanciful, mordant, fecund . . . ‘It’s too good to be science fiction,’ [the critics] would say. But Vonnegut doesn’t care, and you won’t care, either, because this is a writer who leaps over genres.”—Los Angeles Times

Sample

Chapter One

All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn't his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I've changed all the names.

I really did go back to Dresden with Guggenheim money (God love it) in 1967. It looked a lot like Dayton, Ohio, more open spaces than Dayton has. There must be tons of human bone meal in the ground.

I went back there with an old war buddy, Bernard V. O'Hare, and we made friends with a cab driver, who took us to the slaughterhouse where we had been locked up at night as prisoners of war. His name was Gerhard Müller. He told us that he was a prisoner of the Americans for a while. We asked him how it was to live under Communism, and he said that it was terrible at first, because everybody had to work so hard, and because there wasn't much shelter or food or clothing. But things were much better now. He had a pleasant little apartment, and his daughter was getting an excellent education. His mother was incinerated in the Dresden fire-storm. So it goes.

He sent O'Hare a postcard at Christmastime, and here is what it said:

"I wish you and your family also as to your friend Merry Christmas and a happy New Year and I hope that we'll meet again in a world of peace and freedom in the taxi cab if the accident will."

I like that very much: "If the accident will."

I would hate to tell you what this lousy little book cost me in money and anxiety and time. When I got home from the Second World War twenty-three years ago, I thought it would be easy for me to write about the destruction of Dresden, since all I would have to do would be to report what I had seen. And I thought, too, that it would be a masterpiece or at least make me a lot of money, since the subject was so big.

But not many words about Dresden came from my mind then -- not enough of them to make a book, anyway. And not many words come now, either, when I have become an old fart with his memories and his Pall Malls, with his sons full grown.

I think of how useless the Dresden part of my memory has been, and yet how tempting Dresden has been to write about, and I am reminded of the famous limerick:

There was a young man from Stamboul, Who soliloquized thus to his tool: "You took all my wealth And you ruined my health, And now you won't pee, you old fool."

And I'm reminded, too, of the song that goes:

My name is Yon Yonson, I work in Wisconsin, I work in a lumbermill there. The people I meet when I walk down the street, They say, "What's your name?" And I say, My name is Yon Yonson, I work in Wisconsin..."

And so on to infinity.

Over the years, people I've met have often asked me what I'm working on, and I've usually replied that the main thing was a book about Dresden.

I said that to Harrison Starr, the movie-maker, one time, and he raised his eyebrows and inquired, "Is it an anti-war book?"

"Yes," I said. "I guess."

"You know what I say to people when I hear they're writing anti-war books?"

"No. What do you say, Harrison Starr?"

"I say, 'Why don't you write an anti-glacier book instead?' "

What he meant, of course, was that there would always be wars, that they were as easy to stop as glaciers. I believe that, too.

And even if wars didn't keep coming like glaciers, there would still be plain old death.

When I was somewhat younger, working on my famous Dresden book, I asked an old war buddy named Bernard V. O'Hare if I could come to see him. He was a district attorney in Pennsylvania. I was a writer on Cape Cod. We had been privates in the war, infantry scouts. We had never expected to make any money after the war, but we were doing quite well.

I had the Bell Telephone Company find him for me. They are wonderful that way. I have this disease late at night sometimes, involving alcohol and the telephone. I get drunk, and I drive my wife away with a breath like mustard gas and roses. And then, speaking gravely and elegantly into the telephone, I ask the telephone operators to connect me with this friend or that one, from whom I have not heard in years.

I got O'Hare on the line in this way. He is short and I am tall. We were Mutt and Jeff in the war. We were captured together in the war. I told him who I was on the telephone. He had no trouble believing it. He was up. He was reading. Everybody else in his house was asleep.

"Listen--" I said, "I'm writing this book about Dresden. I'd like some help remembering stuff. I wonder if I could come down and see you, and we could drink and talk and remember."

He was unenthusiastic. He said he couldn't remember much. He told me, though, to come ahead.

"I think the climax of the book will be the execution of poor old Edgar Derby," I said. "The irony is so great. A whole city gets burned down, and thousands and thousands of people are killed. And then this one American foot soldier is arrested in the ruins for taking a teapot. And he's given a regular trial, and then he's shot by a firing squad."

"Um," said O'Hare.

"Don't you think that's really where the climax should come?"

"I don't know anything about it," he said. "That's your trade, not mine."

As a trafficker in climaxes and thrills and characterization and wonderful dialogue and suspense and confrontations, I had outlined the Dresden story many times. The best outline I ever made, or anyway the prettiest one, was on the back of a roll of wallpaper.

I used my daughter's crayons, a different color for each main character. One end of the wallpaper was the beginning of the story, and the other end was the end, and then there was all that middle part, which was the middle. And the blue line met the red line and then the yellow line, and the yellow line stopped because the character represented by the yellow line was dead. And so on. The destruction of Dresden was represented by a vertical band of orange cross-hatching, and all the lines that were still alive passed through it, came out the other side.

The end, where all the lines stopped, was a beetfield on the Elbe, outside of Halle. The rain was coming down. The war in Europe had been over for a couple of weeks. We were formed in ranks, with Russian soldiers guarding us -- Englishmen, Americans, Dutchmen, Belgians, Frenchmen, Canadians, South Africans, New Zealanders, Australians, thousands of us about to stop being prisoners of war.

And on the other side of the field were thousands of Russians and Poles and Yugoslavians and so on guarded by American soldiers. An exchange was made there in the rain -- one for one. O'Hare and I climbed into the back of an American truck with a lot of others. O'Hare didn't have any souvenirs. Almost everybody else did. I had a ceremonial Luftwaffe saber, still do. The rabid little American I call Paul Lazzaro in this book had about a quart of diamonds and emeralds and rubies and so on. He had taken these from dead people in the cellars of Dresden. So it goes.

An idiotic Englishman, who had lost all his teeth somewhere, had his souvenir in a canvas bag. The bag was resting on my insteps. He would peek into the bag every now and then, and he would roll his eyes and swivel his scrawny neck, trying to catch people looking covetously at his bag. And he would bounce the bag on my insteps.

I thought this bouncing was accidental. But I was mistaken. He had to show somebody what was in the bag, and he had decided he could trust me. He caught my eye, winked, opened the bag. There was a plaster model of the Eiffel Tower in there. It was painted gold. It had a clock in it.

"There's a smashin' thing," he said.

And we were flown to a rest camp in France, where we were fed chocolate malted milkshakes and other rich foods until we were all covered with baby fat. Then we were sent home, and I married a pretty girl who was covered with baby fat, too.

Read more

About the authors

Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut was a writer, lecturer and painter. He was born in Indianapolis in 1922 and studied biochemistry at Cornell University. During WWII, as a prisoner of war in Germany, he witnessed the destruction of Dresden by Allied bombers, an experience which inspired Slaughterhouse Five. First published in 1950, he went on to write fourteen novels, four plays, and three short story collections, in addition to countless works of short fiction and nonfiction. He died in 2007.

Read more

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.4 out of 5

34,268 global ratings

Joey Lott

5

Wonderful, Heartbreaking, Human

Reviewed in the United States on December 12, 2014

Verified Purchase

I recently purchased this book and read it for the second (or third?) time, having last read it over 15 years ago. I remembered it being good, though not my favorite Vonnegut novel. (Mother Night is probably still my favorite simply because I find that I think of it often, because the moral of the story remains poignant and because the complexities of the story remain interesting and provocative.) I was curious to re-read it because I was reminded that this was one of Vonnegut's favorites of his own novels. (He rated it an A-plus along with Cat's Cradle. Interestingly, he rated Slipstick a D, and I found Slapstick to be a wonderful book - also one that I reflect on often. But then again, I actually love all Vonnegut writing because even his worst is better than most everything else.)

This most recent reading upgraded my opinion from good to great. Still, I favor other Vonnegut novels. As I wrote, Mother Night may be one of my favorites, and I also love Bluebeard. But Slaughterhouse Five is certainly worthy of the praise it receives. It showcases the genius of Vonnegut - moralistic yet nihilistic, pointless yet poignant, heartbreaking, uproarious, and deeply human while at the same time bizarre and alien. I loved every minute of it - every sentence. Vonnegut certainly sticks to his own rules of writing. Not a sentence is wasted. No fluff. Nothing flowery or uninteresting. Nothing overly complex. He keeps it simple and yet in so doing causes the reader to question and wonder and look more deeply into his or her own heart.

One thing that is rather obnoxious, however, is that the Kindle version (which I purchased) is rife with errors. I noticed formatting and capitalization errors throughout. The errors are not enough to make it unreadable, but it is obnoxious to be charged $5.99 for a Kindle version in which it is evident that basic proofreading was not applied. That seems unprofessional and rude. If I was being charged $0.99 I wouldn't even make mention of it. But $5.99? I expect reasonable efforts to be made to produce a professional quality product. Why I am bothering to write this critique, I don't know, because with 1720 reviews as of this writing, I can't imagine that RossettaBooks, the publisher of the Kindle version, can be bothered to read this one. But in the nearly infinitesimal chance that someone from the publisher does read this, please proofread these books before publishing them.

Read more

14 people found this helpful

P. M. Bradshaw

5

Beautiful and sorrowful.

Reviewed in the United States on May 8, 2024

Verified Purchase

This book is brilliant and beautiful. It resonates not and utter sorrow. It is somehow simple, and at the same time, complex. It's about living g in the aftermath of war and despair. Everyone should read this book at least once in their life.

3 people found this helpful

Amazon Customer

5

I absolutely loved this book!

Reviewed in the United States on May 26, 2024

Verified Purchase

I wasn’t sure I was going to like this book. It was sort of a book within a book. It starts off with a writer, who I assume was Vonnegut, suffering from writers block. Unable to write about his experiences during WW2, especially the bombing at Dresden, which he witnessed. He complained of having very little recollection of his time in the war. He consulted a friend to see if his experiences dragged his memory. But ended up upsetting the man’s wife, who believed he’d glamorized the experience. After reassuring her he wouldn’t, he delivered to his editor the story of Billy Pilgrim. This is we’re our story takes off. With Billy, a man unstuck from time. The book jumped back and forth through Billy’s life. We saw what shaped the man he would become. His experiences before, during and after the war. Billy was a very unreliable narrator. We didn’t know if this was all a hallucination of his mind. At one point we learn he was kidnapped by 4th dimensional aliens who kept him in a zoo. At the same time he was obsessed with Science Fiction books that depicted the exact same scenario he described. The book was great. Whether, Tralfalmadorians really did kidnap him or not is not clear, but what is clear is that Kurt Vonnegut was an incredible writer.

Read more

Similar Books

Best sellers

View all

The Tuscan Child

4.2

-

100,022

$8.39

The Thursday Murder Club: A Novel (A Thursday Murder Club Mystery)

4.3

-

155,575

$6.33

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

4.6

-

140,302

$13.49

The Butterfly Garden (The Collector, 1)

4.3

-

88,556

$9.59

Things We Hide from the Light (Knockemout Series, 2)

4.4

-

94,890

$11.66

The Last Thing He Told Me: A Novel

4.3

-

154,085

$2.99

The Perfect Marriage: A Completely Gripping Psychological Suspense

4.3

-

143,196

$9.47

The Coworker

4.1

-

80,003

$13.48

First Lie Wins: A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.3

-

54,062

$14.99

Mile High (Windy City Series Book 1)

4.4

-

59,745

$16.19

Layla

4.2

-

107,613

$8.99

The Locked Door

4.4

-

94,673

$8.53