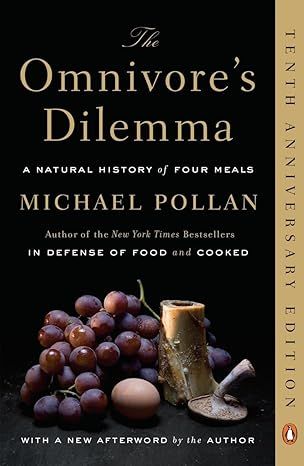

The Omnivore's Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals

4.6

-

5,359 ratings

"Outstanding . . . a wide-ranging invitation to think through the moral ramifications of our eating habits." —The New Yorker

One of the New York Times Book Review's Ten Best Books of the Year and Winner of the James Beard Award

Author of This is Your Mind on Plants, How to Change Your Mind and the #1 New York Times Bestseller In Defense of Food and Food Rules

What should we have for dinner? Ten years ago, Michael Pollan confronted us with this seemingly simple question and, with The Omnivore’s Dilemma, his brilliant and eye-opening exploration of our food choices, demonstrated that how we answer it today may determine not only our health but our survival as a species. In the years since, Pollan’s revolutionary examination has changed the way Americans think about food. Bringing wide attention to the little-known but vitally important dimensions of food and agriculture in America, Pollan launched a national conversation about what we eat and the profound consequences that even the simplest everyday food choices have on both ourselves and the natural world. Ten years later, The Omnivore’s Dilemma continues to transform the way Americans think about the politics, perils, and pleasures of eating.

Kindle

$14.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$15.25

Paperback

$10.24

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

0143038583

ISBN-13

978-0143038580

Print length

450 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Penguin

Publication date

August 27, 2007

Dimensions

5.49 x 1.02 x 8.41 inches

Item weight

2.31 pounds

Popular Highlights in this book

There are some forty-five thousand items in the average American supermarket and more than a quarter of them now contain corn.

Highlighted by 3,933 Kindle readers

Wet milling is an energy-intensive way to make food; for every calorie of processed food it produces, another ten calories of fossil fuel energy are burned.

Highlighted by 3,017 Kindle readers

Product details

ASIN :

B000SEIDR0

File size :

1347 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Editorial Reviews

Gold Medal in Nonfiction for the California Book Award • Winner of the 2007 Bay Area Book Award for Nonfiction • Winner of the 2007 James Beard Book Award/Writing on Food Category • Finalist for the 2007 Orion Book Award • Finalist for the 2007 NBCC Award

"Thoughtful, engrossing . . . You're not likely to get a better explanation of exactly where your food comes from." —The New York Times Book Review

"An eater's manifesto . . . [Pollan's] cause is just, his thinking is clear, and his writing is compelling. Be careful of your dinner!" —The Washington Post

"Outstanding . . . a wide-ranging invitation to think through the moral ramifications of our eating habits." —The New Yorker

"If you ever thought 'what's for dinner?' was a simple question, you'll change your mind after reading Pollan's searing indictment of today's food industry-and his glimpse of some inspiring alternatives . . . I just loved this book so much I didn't want it to end." —The Seattle Times

“Michael Pollan has perfected a tone—one of gleeful irony and barely suppressed outrage—and a way of inserting himself into a narrative so that a subject comes alive through what he’s feeling and thinking. He is a master at drawing back to reveal the greater issues.” —Los Angeles Times

“Michael Pollan convincingly demonstrates that the oddest meal can be found right around the corner at your local McDonald’s . . . He brilliantly anatomizes the corn-based diet that has emerged in the postwar era.” —The New York Times

“[Pollan] wants us at least to know what it is we are eating, where it came from and how it got to our table. He also wants us to be aware of the choices we make and to take responsibility for them. It’s an admirable goal, well met in The Omnivore’s Dilemma.” —The Wall Street Journal

“A gripping delight . . . This is a brilliant, revolutionary book with huge implications for our future and a must-read for everyone. And I do mean everyone.” —The Austin Chronicle

“As lyrical as What to Eat is hard-hitting, Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore's Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals…may be the best single book I read this year. This magisterial work, whose subject is nothing less than our own omnivorous (i.e., eating everything) humanity, is organized around two plants and one ecosystem. Pollan has a love-hate relationship with ‘Corn,’ the wildly successful plant that has found its way into meat (as feed), corn syrup and virtually every other type of processed food. American agribusiness’ monoculture of corn has shoved aside the old pastoral ideal of ‘Grass,’ and the self-sustaining, diversified farm based on the grass-eating livestock. In ‘The Forest,’ Pollan ponders the earliest forms of obtaining food: hunting and gathering. If you eat, you should read this book.” —Newsday

“Smart, insightful, funny and often profound.” —USA Today

“The Omnivore’s Dilemma is an ambitious and thoroughly enjoyable, if sometimes unsettling, attempt to peer over these walls, to bring us closer to a true understanding of what we eat—and, by extension, what we should eat . . . It is interested not only in how the consumed affects the consumer, but in how we consumers affect what we consume as well . . . Entertaining and memorable. Readers of this intelligent and admirable book will almost certainly find their capacity to delight in food augmented rather than diminished.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“On the long trip from the soil to our mouths, a trip of 1,500 miles on average, the food we eat often passes through places most of us will never see. Michael Pollan has spent much of the last five years visiting these places on our behalf.” —Salon.com

“The author of Second Nature and The Botany of Desire, Pollan is willing to go to some lengths to reconnect with what he eats, even if that means putting in a hard week on an organic farm and slitting the throats of chickens. He’s not Paris Hilton on The Simple Life.” —Time

“A pleasure to read.” —The Baltimore Sun

“A fascinating journey up and down the food chain, one that might change the way you read the label on a frozen dinner, dig into a steak or decide whether to buy organic eggs. You’ll certainly never look at a Chicken McNugget the same way again . . . Pollan isn’t preachy; he’s too thoughtful a writer and too dogged a researcher to let ideology take over. He’s also funny and adventurous.” —Publishers Weekly

“[Pollan] does everything from buying his own cow to helping with the open-air slaughter of pasture-raised chickens to hunting morels in Northern California. This is not a man who’s afraid of getting his hands dirty in the quest for better understanding. Along with wonderfully descriptive writing and truly engaging stories and characters, there is a full helping of serious information on the way modern food is produced.” —BookPage

“The Omnivore’s Dilemma is about something that affects everyone.” —The Sacramento Bee

“Lively and thought-provoking.” —East Bay Express

“Michael Pollan makes tracking your dinner back through the food chain that produced it a rare adventure.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

“A master wordsmith…Pollan brings to the table lucid and rich prose, an enthusiasm for his topic, interesting anecdotes, a journalist’s passion for research, an ability to poke fun at himself, and an appreciation for historical context . . . This is journalism at its best.” —Christianity Today

“First-rate . . . [A] passionate journey of the heart…Pollan is . . . an uncommonly graceful explainer of natural science; this is the book he was born to write.” —Newsweek

“[Pollan’s] stirring new book . . . is a feast, illuminating the ethical, social and environmental impacts of how and what we choose to eat.” —The Courier-Journal

“From fast food to ‘big’ organic to locally sourced to foraging for dinner with rifle in hand, Pollan captures the perils and the promise of how we eat today.” —The Arizona Daily Star

“A multivalent, highly introspective examination of the human diet, from capitalism to consumption.” —The Hudson Review

“What should you eat? Michael Pollan addresses that fundamental question with great wit and intelligence, looking at the social, ethical, and environmental impact of four different meals. Eating well, he finds, can be a pleasurable way to change the world.” —Eric Schlosser, author of Fast Food Nation and Reefer Madness

“Widely and rightly praised…The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals [is] a book that—I kid you not—may change your life.” —Austin American-Statesman

Sample

ONE

THE PLANT

Corn’s Conquest

1. A NATURALIST IN THE SUPERMARKET

Air-conditioned, odorless, illuminated by buzzing fluorescent tubes, the American supermarket doesn’t present itself as having very much to do with Nature. And yet what is this place if not a landscape (man-made, it’s true) teeming with plants and animals?

I’m not just talking about the produce section or the meat counter, either—the supermarket’s flora and fauna. Ecologically speaking, these are this landscape’s most legible zones, the places where it doesn’t take a field guide to identify the resident species. Over there’s your eggplant, onion, potato, and leek; here your apple, banana, and orange. Spritzed with morning dew every few minutes, Produce is the only corner of the supermarket where we’re apt to think “Ah, yes, the bounty of Nature!” Which probably explains why such a garden of fruits and vegetables (sometimes flowers, too) is what usually greets the shopper coming through the automatic doors.

Keep rolling, back to the mirrored rear wall behind which the butchers toil, and you encounter a set of species only slightly harder to identify—there’s chicken and turkey, lamb and cow and pig. Though in Meat the creaturely character of the species on display does seem to be fading, as the cows and pigs increasingly come subdivided into boneless and bloodless geometrical cuts. In recent years some of this supermarket euphemism has seeped into Produce, where you’ll now find formerly soil-encrusted potatoes cubed pristine white, and “baby” carrots machine-lathed into neatly tapered torpedoes. But in general here in flora and fauna you don’t need to be a naturalist, much less a food scientist, to know what species you’re tossing into your cart.

Venture farther, though, and you come to regions of the supermarket where the very notion of species seems increasingly obscure: the canyons of breakfast cereals and condiments; the freezer cases stacked with “home meal replacements” and bagged platonic peas; the broad expanses of soft drinks and towering cliffs of snacks; the unclassifiable Pop-Tarts and Lunchables; the frankly synthetic coffee whiteners and the Linnaeus-defying Twinkie. Plants? Animals?! Though it might not always seem that way, even the deathless Twinkie is constructed out of…well, precisely what I don’t know offhand, but ultimately some sort of formerly living creature, i.e., a species. We haven’t yet begun to synthesize our foods from petroleum, at least not directly.

If you do manage to regard the supermarket through the eyes of a naturalist, your first impression is apt to be of its astounding biodiversity. Look how many different plants and animals (and fungi) are represented on this single acre of land! What forest or prairie could hope to match it? There must be a hundred different species in the produce section alone, a handful more in the meat counter. And this diversity appears only to be increasing: When I was a kid, you never saw radicchio in the produce section, or a half dozen different kinds of mushrooms, or kiwis and passion fruit and durians and mangoes. Indeed, in the last few years a whole catalog of exotic species from the tropics has colonized, and considerably enlivened, the produce department. Over in fauna, on a good day you’re apt to find—beyond beef—ostrich and quail and even bison, while in Fish you can catch not just salmon and shrimp but catfish and tilapia, too. Naturalists regard biodiversity as a measure of a landscape’s health, and the modern supermarket’s devotion to variety and choice would seem to reflect, perhaps even promote, precisely that sort of ecological vigor.

Except for the salt and a handful of synthetic food additives, every edible item in the supermarket is a link in a food chain that begins with a particular plant growing in a specific patch of soil (or, more seldom, stretch of sea) somewhere on earth. Sometimes, as in the produce section, that chain is fairly short and easy to follow: As the netted bag says, this potato was grown in Idaho, that onion came from a farm in Texas. Move over to Meat, though, and the chain grows longer and less comprehensible: The label doesn’t mention that that rib-eye steak came from a steer born in South Dakota and fattened in a Kansas feedlot on grain grown in Iowa. Once you get into the processed foods you have to be a fairly determined ecological detective to follow the intricate and increasingly obscure lines of connection linking the Twinkie, or the nondairy creamer, to a plant growing in the earth someplace, but it can be done.

Read more

About the authors

Michael Pollan

Michael Pollan is the author of seven previous books, including Cooked, Food Rules, In Defense of Food, The Omnivore's Dilemma and The Botany of Desire, all of which were New York Times bestsellers. A longtime contributor to the New York Times Magazine, he also teaches writing at Harvard and the University of California, Berkeley. In 2010, TIME magazine named him one of the one hundred most influential people in the world.

Read more

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.6 out of 5

5,359 global ratings

James Charnock

5

A National Health Dilemma

Reviewed in the United States on September 18, 2011

Verified Purchase

This was a big book full of intensity and good detail. In parts it was almost poetic. I found I could not do it justice by summarizing the author's ideas in my own words, so I am going to do a lot of quoting. Believe me, there is much more, and you should read the book.

The author contends that not only excess corn--and all the unnecessary products from it--and the introduction of GMO seed have wrecked havoc with our farm system as well as, perhaps, our body's health system. "By the 1980s the diversified family farm was history in Iowa, and corn was king" (p. 39). A lack of diversification meant more plagues of insects and crop diseases. Amazingly, the author states that "the farmers in Iowa...don't respect corn [but] will tell you in disgust that the plant has become a `welfare queen'." Hybrid flowers and tomatoes sound great, but hybrid corn consumes more polluting fertilizer than any crop (p 41). Iowa, which was once our breadbasket, now imports 80 percent of its food--and this was in 2006.

The world would be much less populated had a scientist not figured out how to "make" nitrogen apart from nature doing so. About 60 percent of American commodity corn is fed to livestock which in times past spent most of their lives grazing on grasses (p 66). "The urbanization of America's animal population [in feed lots] would never have taken place if not for the advent of cheap, federally- subsidized corn" (67). Even farm salmon are now being fed on excess biomass corn (p 67). E-coli bacteria thrives in the feedlot cattle--40 percent carry it in their gut; they produce a toxin that destroys human kidneys.

Concentrated feed lots take the youngish cows off their natural diet of grass and force feed them corn, which they would not otherwise eat. Corn just does not work with their stomachs and they are prone to illnesses for which antibiotics are used. Producers believe price is the overriding issue when it comes to food purchasing, so producing a "product" as cheaply as possible is what guides most of our feed lots. For healthy products to healthy people you must buy locally: fruits, vegetables, meat and dairy. "Artificial manures [synthetic fertilizers] lead inevitably to artificial nutrition, artificial food, artificial animals, and finally to artificial men and women" (pp 128, 148).

"The simplist way to capture the sun's energy in a form animals can use is by growing grass" (p 189). "For example, if the 16 million acres now being used to grow corn to feed cows,...became well-managed pasture, that would remove 14 billion pounds of carbon from the atmosphere each year, the equivalent of taking four million cars off the road" (p 198).

"The government writes no subsidy checks to grass farmers. Grass farmers, who buy little...pesticides and fertilizers, do little to support agribusiness or the pharmaceutical industry or big oil" (p 201).

The best thing for our health and our animal's is "relationship marketing," buying directly from farmers or co-ops. You must become a non-Barcode person as much as possible when it comes to food. You have to decide if you want to buy honestly priced food or irresponsibly priced (and polluted) food (p. 240, 241). "Our food system depends on consumers not knowing much about [their food] beyond the price disclosed by the checkout scanner. Cheapness and ignorance are mutually reinforcing" (p 245).

If the American Joe and Jane don't push for change, America's chefs may "be leading a movement to save small farmers and reform America's food system" (p 245). This is going to be a real MOVEMENT, perhaps along with the following:

- anti-globalization ("globalization [or global capitalization] proposes to sacrifice [our ability to feed ourselves] in the name of efficiency and economic growth" [p 256])

- anti-genetically modified crops

- anti-patented seeds pushed by the WTO (the World Trade Organization)

- Slow Food, which defends traditional food cultures against the global tide of homogenization

"A successful local food economy implies not only a new kind of food producer, but a new kind of eater, one who regards finding, preparing and preserving food as one of the pleasures of life rather than a chore" (p 259).

"A growing body of scientific research indicates that pasture substantially changes the nutritional profile of chicken and eggs, as well as beef and milk. ... [Also] as it turns out, the fats in the flesh of grass eaters are the best kind for us to eat" (p 267).

I only enjoyed Chapters 1-14 (Sections I and II); the final Chapters of 15-20 (Section III) I found somewhat off point to the previous sections. You can ignore it and get the point/s of the author quite powerfully, even though this final section accounts for one-third of the book.

Read more

15 people found this helpful

D

5

One of the best books I've ever read - 9.5/10

Reviewed in the United States on April 12, 2020

Verified Purchase

I almost never write reviews, but after the amount of time I devoted to reading this book and the gratefulness I have to Mr. Pollan for researching and sharing his knowledge and wisdom within it, I feel obligated.

The book is well organized into Contents of 3 Parts: Industrial (Corn), Pastoral (Grass), and Personal (Forest). I have no idea why "Personal" was chosen over the term Hunter-Gatherer, as that was what he was going for. You may have picked up on that the Contents are in reverse chronological order, a timeline from current to pre-historic. In case you are wondering what "A Natural History of Four Meals" refers to, it is those three aforementioned Parts with Pastoral being subdivided into Big Organic/Industrial Organic and Small/Local organic. Pollan's admirable and ambitious goal is to figure out how our food in the USA gets from earth to plate in each category.

Part I - Industrial has a lot of eye-opening information in regards to farming, ranching, and the science. Even with all of that great information I found it the hardest part to get through as Pollan beats the metaphorical horse to death lambasting the industrial food system. I didn't make it through Part I the first time I tried reading it 10 years ago and now I can see why. Even though it is the shortest of the 3 parts there is a redundancy and negativity where I felt it should have been edited down even further.

Part II - Pastoral is the longest of the 3 parts and was my favorite part of the book. I grew up on a farm/ranch and some of the descriptions and emotions that he conveyed took me right back onto my family farm. I don't think it would be much of a reach to assume Pollan a lefty/liberal city slicker having grown up in the New England, moved to California and teaching at Berkley, but in his writings of the "grass farmer" Joel you can tell how much respect and admiration he has for the man even though their personal and political beliefs may be worlds apart. I also thought Pollan's critique and DILEMMAs he posed in this section led to some of his best writing in the book.

Part III - Personal was a excellent conclusion to the book, though it does have a completely different tone to it. The first two Parts (Industrial and Pastoral) are an examination of the US food system. This last part is Pollan doing his best to recreate the hunter-gatherer food lifestyle while living in urban California, in hopes that it will add to the big picture he painted for us in the first two parts. As someone who grew up on a farm hunting it was refreshing to have a novice from the city, who likely looked down on us in someway, dive fully into the hunter outdoorsmen experience to understand our way of life. I'd be proud to buy Mr. Pollan a beer congratulating him on his first successful hunt. I also found the chapters on the mysterious mushrooms and preparing the food educational and entertaining. Angelo in particular seems like pretty cool, kickass dude.

A few critiques: Mr. Pollan frequently uses personification when talking about plants and their evolution, like when he makes statements that corn chose us as much as we chose it. That's not how it works and I found it to be a distracting and annoying repeated offense.

Finished in late 2005, the book could use an update on the farming end. The farmers had a nice run for a stretch, lets say 2009-2015. Things have turned really ugly in both the cattle markets and commodity markets since then. It would be nice to see an update of why things turned around for the better, then flipped again. And we could always use a few more wise words from Mr. Joel Salatin.

Looking forward to reading and reviewing "In Defense of Food".

Read more

23 people found this helpful

Steve Chernoski

5

I could go on and on . . (look below)

Reviewed in the United States on July 31, 2006

Verified Purchase

When I bought this book for my dad he simply said, "A book about food?" I laughed and tried to tell him it is probably more about what is wrong with the country (government, business, foreign policy) than it is about food.

I heard Michael Pollan speak on NPR about this book and that sparked my interest. He was railing against corn as he does in the first section of the book here: For instance, I had no idea we used so much fossil fuel to get corn to grow as much as it does. The book provides plenty of other interesting facts that most people don't know (or want to) about their food.

- We feed cattle (the cattle we eat) corn. OK. Seems fine. But I never knew cows are not able to digest corn. We give them corn so the corn farmers -who are protected by subsidies and at the same time hurt by them - can get rid of all the excess corn we produce - (more of the excess goes into high fructose corn syrup which is used in coke and many other soft drinks). This sees company owned farms injecting their cattle with antibiotics so they can digest the corn. Not just to shed farmers' excess corn but to also:

a) Get the cow fatter in a shorter amount of time because . .

b) A cow on this diet could really only survive 150 days before the acidity of the corn eats away at the rumen (a special cow digestive organ FOR GRASS, not corn).

c) Also the pharmaceutical companies get big profits because they manufacture large amounts of antibiotics for these large mammals.

All this may lead to increase in fat content and other peculiarities in the meat we eat.

- The amount of fossil fuel we use to grow food is ridiculous and helps keeps the Saudis happy. If you buy an apple from Washington and live in New Jersey, think of how much gas went into transporting that fruit to me! Better to buy from Iowa. Better than that: buy from a farmer's market and this is one of Pollan's main suggestions:

Buy your food local and maybe you can even find out what is exactly in your hot dog.

-

CAFOS - large corporate feeding pens - where pigs (who are very smart animals) and even chickens display signs of suicidal tendencies.

-

Pollan talks about Big Organic and spends a lot of time here. "Big Organic" is seemingly an oxymoron. He shows how Big Organic companies treat their animals and farms in many similar ways to other industrial farms. However, he makes you think by talking to one organic executive who says,

"Get over it . . . the real value of putting organic on an industrial scale, is the sheer amount of acreage it puts under organic management. Behind every organic TV dinner or chicken or carton of industrial organic milk stands a certain quantity of land that will no longer be doused with chemicals, an undeniable gain of the environment and public health." - pg. 158

True, but the similarities between big companies and how supermarkets only want to deal with them is what Pollan thinks is the problem with our food.

- Pollan focuses the most of his book on Joel Salatin's Polyface Farms in rural Virginia. Salatin calls himself a "grass farmer" (no not THAT grass). You could call it "real organic" but for Pollan it is how we should be farming and what we should eat. Cows, chickens, pigs roaming freely eating grass, and tasting like they should in the end. The problem is that not every area of the USA is as fertile as southwestern Virginia . . .but I am sure Pollan would suggest that each region should specialize in its delicacies and get used to not eating things that aren't in season or animals we don't see. It would be hard for the average American to not be provided with bananas from January - December, but if we want to cut back on fossil fuels (though Pollan notes - trade is good), if we want our eggs to taste like eggs and chicken to taste like chickens and not McChickens, we need to do a better job of eating local. This sends Pollan on his final journey, to hunt for his own food and provide his helpers, with a meal totally foraged by him.

A lot of cool facts here that I never knew or took the time to care about (I never knew the mushroom was so mysterious). I would have liked him to talk more about trade, different areas' food specialties and also how preparing a meal such as his at the end seems a little too time consuming even for the outdoors enthusiast.

I think all Americans - conservatives, liberals, whatevers - can enjoy this book. Liberals for the "return to nature mentality," conservatives for the same reason: Pollan rails into Animal Rights' activists and shows how though they may have good intentions; they would rather upset the balance of nature before they kill anything.

Ominvore's Dilemma is a tremendous contribution, exposing how big corporations and old government practices continue to harm us and our country. The way we thought about food was changed with "Super Size Me" hopefully this book will change they way we want to go about obtaining our food.

Read more

687 people found this helpful

Harrison Bergeron

5

One of the most important books in decades

Reviewed in the United States on April 26, 2007

Verified Purchase

I have to say, this is one fantastic book. Amazing. One of those rare books that forces your eyes wide open to an issue that you'd only dimly been aware of. It's one of those books everyone in the country should read, one that should be of cataclysmic proportions and Change Everything.

I won't destroy the effect of the book by trying to re-state the information in the book and doing a bad job. Let's just say that everyone who eats food should read it.

As a rationalist, I've always been sympathetic to the "Organic foods" movement but uncomfortable with all the pseudo-mystical thinking that's often associated with it. It made sense to me in principle that growing food the way evolution intended made sense, but I found the arguments I often encountered to often be mostly feel-good, unspecific talk about Cycles of Nature and Gaia and Earth Mother and so on. They weren't fact-y enough for me. This book definitely is. It doesn't have one pseudoscientific vibe to it. Conservatives can read it just as comfortably as the most crunchy-granola hippie.

Pollan should have won a Pulitzer Prize for this book. It's magnificently researched and written. It has plenty of hard fact, but instead of being boring, his clear, simple writing brings them to life and gives them meaning. He makes his cases carefully, using evidence and fact, and gradually builds to conclusions that I'm forced to admit are inescapable. It's one of those few fantastic books that takes a subject that's usually dull and dry and makes it not just interesting but, at least for me, gripping. It not only educated me about a whole hell of a lot of things I didn't know, but it walked me though, step by logical step, the reasons why the way our current food production system is seriously broken and horrible for us the consumers, for the farmers, for the plants and animals involved, and for the planet. I had heard this time and time again from various people, but I always took it with a big grain of salt because the people saying these things also often said ridiculous things about other topics, and I thought their virulence might be largely fed by generic anti-capitalist bias.

While I was never exactly an opponent of natural foods or a fan of factory farming, my feelings were nonspecific because I hadn't really looked into it very much, and I had a real skepticism of all the wild accusations made by the more radical people in some movements. But now, I'm convinced. Michael Pollan has presented me with actual objective facts, presented clearly and logically, in an unbiased way, and convinced me through the sheer power of his reasoning. My mind wasn't changed 180 degrees, but it was definitely changed 90 degrees. In some cases the logic is so clear it had me practically slapping my forehead in shock at how stupid people can be. It's been quite a long time since I've been so captivated by the crystal clear beauty of the elegant logic in a perfectly crafted argument.

One thing I like best is that Pollan is largely unbiased himself. Yes, the book does come to conclusions that are very much against some practices and for very much for others, but he makes the arguments so clear and strong that you can only end up agreeing with him. He doesn't, for example, come out with a glowing, uncritical, credulous affirmation of "organic" food, as I had expected. While generally positive, he acknowledges serious problems with the system.

I can't recommend this book any more strongly. If it's completely ignored by government and industry - and I'm sure it will be - it's a crime. This may be the most important book in decades.

Read more

19 people found this helpful

Tintin

4

Philosophical, Informative, and with Field Trips too

Reviewed in the United States on May 30, 2012

Verified Purchase

The Omnivore's Dilemma (a review) Probably, if you were going to read it you have already, but if you haven't ... you might want to pick it up. It was the #1 New York Times Bestseller in 2006 and it's still quite relevant today -- maybe more so, who knows.

Normally we may think of evolution as a drive toward complexity, but bacteria has gone the other direction, it's evolved downward into simplicity and into very niche environments. This is an excellent survival strategy - what will survive any catastrophe you can imagine? Somewhere, bacteria, probably.

But most animals have opted for complexity and flexibility instead. They are able to move about and adapt to new environments. But here's the rub: since they choose to be flexible, they have to be flexible.

There is a direct analogy in the gastronomic world, it turns out. Some creatures have taken the simple approach by consuming a limited range of things. They can afford to do this because they have evolved elaborate intestines with which to work food over thoroughly and in which to harbor bacteria which converts one sort of input into all the various nutrients their bodies need. These are the herbivores and carnivores, and genetic code alone, which we call instinct, is sufficient to get them fed. On the other hand, omnivores have taken the high road; their innards are leaner and less elaborate so they must gather the right mix of inputs themselves. And in doing so, they must avoid the dangerous ones. This requires a lot of care, and thought, and therefore ... big brains. It's a tradeoff of a simple lifestyle and an elaborate belly, or a complicated lifestyle, and a lean interior. So the omnivore's dilemma is gathering how to gather the right foods and not take in the harmful kind. That in itself is a dilemma, but Pollan points out there are plenty of moral quandries as well.

The book is as entertaining as The Botany of Desire (2001), in which he looked at the story of apples, potatos, tulips, and marijuana from the plants' perspective. Here he takes on corn, grass, meat, and fungus, and once again we benefit from his careful research and introspection (the latter, occasionally laid on a little thick, for my taste). He also does a great deal of field observation, visiting the food factories and farms, talking to many different kinds of people, gathering mushrooms, and even slitting some chicken necks himself, and shooting a wild boar. He describes much of this so well I felt I had done it too.

His best field trips included a large sustainable farm in Virginia where production is high, costs are relatively low, waste is almost nil, and the animals are mostly content. It's most impressive in the cleverness with which it all works, and the owner explains that in detail. It's a stark contrast to some of the more corporate operations - like a standard corn-fed feedlot, a poultry farm, even an organic farm that turned out to be pretty much like the others. In these chapters the moral dilemmas come into the sharpest focus.

Food -- if you haven't noticed -- has become a new moral battleground, and when Pollan disparaged the new methods, and the lower quality of food they sometimes produce at times I felt he didn't fully appreciate the countervailing moral implications of the much larger quantities turned out now. All that food is a good thing, too. When he marveled that corn production increased from 75 bu/acre in 1950 to 180 in 2006 (140% increase, and often to the detriment of small time farmers), he didn't mention that world population increased by 172% in the same period. Sometimes I though it was a little one-sided because the older methods could not easily produce the food we need now. Hybrid vigor, that gives us pumped up ears of corn, is itself infertile. That's not a Monsanto conspiracy -- as he intimates -- it is a fact of nature. Vigorous hybrids, like mules, are often -- oddly -- infertile. In the end it appears he was sometimes just exploring some of the more extreme views of his interviewees, as his own conclusions seemed balanced and reasonable, in my opinion. As a reader I felt I had been treated fairly.

First, it's corn's dizzying ascendency as a food source, with the field trip to a chemical plant that rips the kernal pulp apart, sending it out in a tangle of different spigots -- some headed for the gas tank, others to the various mixers of myriad foodstuffs, others to make non-edibles. There's a good discussion of the political and economic forces driving the corn industry too. In the second section, on "grass," he works on a the sustainable Virginia farm, among other things. When it comes to meat, he compares the sustainable approach to that in a large organic poultry operation, a feedlot, and commercial slaughterhouse, and more. And all through the book he comments on underlying philosophical issues.

And the section of fungus (mushrooms) is interesting from a botanical perspective, mostly. It could have been in The Botany of Desire. In the end he pulls the story together by describing his "perfect meal" made up of perfect ingredients, served to perfect guests. That just seemed unnecessary, to me but by that time I'd had a good enough intellectual and philosophical material to chew on - enough food for thought, you might say - to forgive him a little retrospective self-indulgence.

Read more

3 people found this helpful

Best Sellers

The Great Alone: A Novel

4.6

-

152,447

$5.49

The Four Winds

4.6

-

156,242

$9.99

Winter Garden

4.6

-

72,838

$7.37

The Nightingale: A Novel

4.7

-

309,637

$8.61

Steve Jobs

4.7

-

24,596

$1.78

Iron Flame (The Empyrean, 2)

4.6

-

164,732

$14.99

A Court of Thorns and Roses Paperback Box Set (5 books) (A Court of Thorns and Roses, 9)

4.8

-

26,559

$37.99

Pretty Girls: A Novel

4.3

-

88,539

$3.67

The Bad Weather Friend

4.1

-

34,750

$12.78

Pucking Around: A Why Choose Hockey Romance (Jacksonville Rays Hockey)

4.3

-

41,599

$14.84

Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action

4.6

-

37,152

$9.99

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow: A novel

4.4

-

95,875

$13.99

Weyward: A Novel

4.4

-

27,652

$11.99

Tom Lake: A Reese's Book Club Pick

4.3

-

37,302

$15.74

All the Sinners Bleed: A Novel

4.4

-

12,894

$13.55

The Mystery Guest: A Maid Novel (Molly the Maid)

4.3

-

9,844

$14.99

Bright Young Women: A Novel

4.2

-

8,485

$14.99

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder (Random House Large Print)

4.5

-

28,672

$14.99

Hello Beautiful (Oprah's Book Club): A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.4

-

79,390

$14.99

Small Mercies: A Detective Mystery

4.5

-

16,923

$10.00

Holly

4.5

-

31,521

$14.99

The Covenant of Water (Oprah's Book Club)

4.6

-

69,712

$9.24

Wellness: A novel

4.1

-

3,708

$14.99

The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession

4.3

-

4,805

$14.99