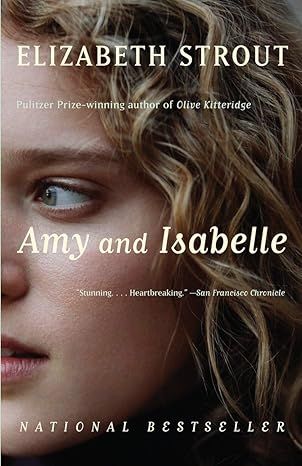

Amy and Isabelle: A novel

4.3

-

9,403 ratings

NATIONAL BESTSELLER • The debut novel from the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Olive Kitteridge evokes a teenager's alienation from her distant mother, and a parent's rage at the discovery of her daughter's secrets.

“One of those rare, invigorating books that take an apparently familiar world and peer into it with ruthless intimacy, revealing a strange and startling place.”—The New York Times Book Review

Before there was Olive Kitteridge, there was Amy and Isabelle…

In most ways, Isabelle and Amy are like any mother and her 16-year-old daughter, a fierce mix of love and loathing exchanged in their every glance. That they eat, sleep, and work side by side in the gossip-ridden mill town of Shirley Falls—a location fans of Strout will recognize from her critically acclaimed novel, The Burgess Boys—only increases the tension. And just when it appears things can't get any worse, Amy's sexuality begins to unfold, causing a vast and icy rift between mother and daughter that will remain unbridgeable unless Isabelle examines her own secretive and shameful past.

A Reader's Guide is included in this powerful first novel by the author who brought Olive Kitteridge to millions of readers.

Kindle

$11.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$3.34

Paperback

$14.50

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

0375705198

ISBN-13

978-0375705199

Print length

303 pages

Language

English

Publisher

Vintage

Publication date

January 31, 2000

Dimensions

5.1 x 0.64 x 8 inches

Item weight

2.31 pounds

Popular highlights in this book

Bewildering that you could harm a child without even knowing, thinking all the while you were being careful, conscientious.

Highlighted by 484 Kindle readers

Lives, flimsy as fabric, could be snipped capriciously with the shears of random moments of self-interest.

Highlighted by 456 Kindle readers

Arriving at the point where she felt almost invisible, she was aware that her solitude was something she might have brought upon herself.

Highlighted by 249 Kindle readers

Product details

ASIN :

B000FBJF8M

File size :

2812 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Award winners:

Editorial reviews

Amazon.com Review

"It was terribly hot the summer Mr. Robertson left town." For Amy Goodrow and her mother, Isabelle, the heat of that summer is the least of their problems. Other citizens in the New England mill town of Shirley Falls are bothered by the heat and by "other things too: Further up the river crops weren't right--pole beans were small, shriveled on the vine, carrots stopped growing when they were no bigger than the fingers of a child; and two UFOs had apparently been sighted in the north of the state." But Amy and Isabelle have a more private misery: a seemingly unbridgeable chasm has opened between this once-close mother and daughter and nothing will ever be the same again. For Amy has fallen in love with her high-school math teacher, Mr. Robertson, who has gone way beyond the bounds of propriety by encouraging the crush. When Isabelle finds out, she is horrified to realize that her anger at him is dwarfed by her rage at her own daughter for "enjoying the sexual pleasures of a man while she herself had not." Mother-daughter novels can, by virtue of their subject matter, often seem claustrophobic, a little overwrought; Elizabeth Strout masterfully avoids this problem by placing Amy and Isabelle in the larger context of the community they inhabit. Though her main focus is on the Goodrow women, Strout often detours into the lives and thoughts of her many secondary characters: Isabelle's coworkers Dottie Brown and Fat Bev; Amy's best friend, Stacy Burrows; Stacy's ex-boyfriend, Paul Bellows; and women from Isabelle's church such as Peg Dunlap and Barbara Rawley. She also introduces a chilling frisson of menace with the unsolved abduction of a 12-year-old girl and a mysterious obscene phone-caller. Like the best of Alice Hoffman, Amy and Isabelle offers up a moving yet resolutely unsentimental portrait of people coming to terms with their lives, finding unsuspected nobility in themselves and unexpected kindness in others along the way. Elizabeth Strout has written a gem of a novel. --Alix Wilber

From Library Journal

YA-Isabelle Goodrow thought her move to the small mill town of Shirley Falls would be temporary-just until she decided in which direction she wanted her life to head. Now her daughter, Amy, has fallen in love with her high school math teacher, and he takes advantage of the teen's infatuation. When the relationship is discovered, Isabelle is furious with her daughter but also a little jealous that Amy has found sexual fulfillment while she has not. As mother and daughter try to rebuild the trust and closeness they once shared, the private secrets of many citizens of Shirley Falls are revealed. YAs will relate to the complexities of mother/daughter relationships and to having a crush on a teacher. This is a beautifully written novel with characters so real that readers will miss them at the book's resolute ending. Their interactions are riveting. Katherine Fitch, Rachel Carson Middle School, Herndon, VA

Copyright 1999 Reed Business Information, Inc.

From Kirkus Reviews

A lyrical, closely observant first novel, charting the complex, resilient relationship of a mother and daughter. Isabel Goodrow had settled in the mill town of Shirley Falls when her daughter Amy was an infant, reluctantly admitting to those who a sked that both her husband and her parents were dead. Amy has grown up knowing little about her father and, thanks to her closeness to Isabel, also knowing little about the rough give-and-take of life. Now, Amy's innocence is under assault from various qu arters, and her mother finds herself losing touch with the daughter who has been the focus of her existence. Amy, at 16, has a poised, delicate beauty, and finds herselfat first with alarm, then with a barely suppressed excitementresponding to the flirtat ions of a new teacher. Part of the novel's power derives from Strout's ability to set Amy and Isabel's painful struggles within the larger context of a small town. Some elements of the life there seem timeless: the steady flow of gossip, the invisible but nonetheless rigid social hierarchies, the ancient disruptions of life (illness, adultery, violence). New elements, however, signal a darker time: UFO's have been sighted, and a young girl is missing and may have been abducted. Strout nicely interweaves t hese elements within the record of Amy and Isabelle's increasingly charged relationship. She catches, with an admirable restraint, and particularity, Amy's emergent sense of self, the wild succession of emotions in adolescence, and Amys stunning discovery of sex. She also renders a wonderfully nuanced portrait of Isabelle, a bright, often angry woman who has only imperfectly replaced passion with stoicism. Matters come to a head when Amy and her teacher are discovered in compromising circumstances, and wh en members of her father's family suddenly get in touch. In less sure hands, all of this would seem merely melodramatic. But Strout demonstrates exceptional poise, and an uncommon ability to render complex emotions with clarity and a sympathetic intellige nce, evoking comparisons with the work of Alice Munro and Anne Tyler. (Author tour) -- Copyright ©1998, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved.

Review

"Strout's insights into the complex psychology bewteen [mother and daughter] result in a poignant tale about two coming of age." —Time

"Impressive....Strout writes with abundant warmth." —People

"Poignant...sensitively imagined...[Amy and Isabelle] recalls the elgegiac charm of Our Town." —The Christian Science Monitor

"Stunning....Every once in a while, a novel comes along that plunges deep into your psyche, leaving you breathless....This year that novel is Amy and Isabelle." —San Francisco Chronicle

"Excellent....Strout's collective portrait...remains unflaggingly engaging....[W]hat a pleasure to gain entry into the world of this book." —The New Yorker

"Lovely, powerful...a kind if modern 'Rapunzel.'" —Newsweek

"Amy and Isabelle is an impressive debut....with an expansiveness and inventiveness that is the mark of a true storyteller." —The Philadelphia Inquirer

From the Back Cover

In most ways, Isabelle and Amy are like any mother and her 16-year-old daughter, a fierce mix of love and loathing exchanged in their every glance. That they eat, sleep, and work side by side in the gossip-ridden mill town of Shirley Falls only increases the tension. And just when it appears things can't get any worse, Amy's sexuality begins to unfold, causing a vast and icy rift between mother and daughter that will remain unbridgeable unless Isabelle examines her own secretive and shameful past. In prose that has merited comparisons to Anne Tyler and Mona Simpson, Elizabeth Strout evokes a teenager's alienation from her distant mother -- and parent's rage at the discovery of her daughter's sexual secrets.

About the Author

Stephanie Roberts is a native of Washington State. She studied acting at Cornish College of the Arts and has been performing, writing, directing, and teaching theater in Seattle and throughout the country for over a decade.

Elizabeth Strout is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Olive Kitteridge, the #1 New York Times bestseller My Name Is Lucy Barton, and the New York Times bestseller The Burgess Boys, as well as Abide with Me, a Book Sense pick, and Amy and Isabelle, which won the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction and the Chicago Tribune Heartland Prize. She has also been a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award and the Orange Prize in England. Her short stories have been published in a number of magazines, including the New Yorker and O: The Oprah Magazine.

Read more

Sample

It was terribly hot that summer Mr. Robertson left town, and for a long while the river seemed dead. Just a dead brown snake of a thing lying flat through the center of town, dirty yellow foam collecting at its edge. Strangers driving by on the turnpike rolled up their windows at the gagging, sulfurous smell and wondered how anyone could live with that kind of stench coming from the river and the mill. But the people who lived in Shirley Falls were used to it, and even in the awful heat it was only noticeable when you first woke up; no, they didn't particularly mind the smell.

What people minded that summer was how the sky was never blue, how it seemed instead that a dirty gauze bandage had been wrapped over the town, squeezing out whatever bright sunlight might have filtered down, blocking out whatever it was that gave things their color, and leaving a vague flat quality to hang in the air-this is what got to people that summer, made them uneasy after a while. And there were other things too: Further up the river crops weren't right-pole beans were small, shriveled on the vine, carrots stopped growing when they were no bigger than the fingers of a child; and two UFOs had apparently been sighted in the north of the state. Rumor had it the government had even sent people to investigate.

In the office room of the mill, where a handful of women spent their days separating invoices, filing copies, pressing stamps onto envelopes with a thump of the fist, there was uneasy talk for a while. Some thought the world might be coming to an end, and even those women not inclined to go that far had to admit it might not have been a good idea sending men into space, that we had no business, really, walking around up there on the moon. But the heat was relentless and the fans rattling in the windows seemed to be doing nothing at all, and eventually the women ran out of steam, sitting at their big wooden desks with their legs slightly apart, lifting the hair from the back of their necks. "Can you believe this" was, after a while, about all that got said.

One day the boss, Avery Clark, had sent them home early, but hotter days followed with no further mention of any early dismissal, so apparently this wasn't to happen again. Apparently they were supposed to sit there and suffer, and they did-the room held on to the heat. It was a big room, with a high ceiling and a wooden floor that creaked. The desks were set in pairs facing each other, two by two, down the length of the room. Metal filing cabinets lined the walls; on top of one sat a philodendron plant, its vines gathered and coiled like a child's clay pot, although some vines escaped and fell almost to the floor. It was the only green thing in the room. A few begonia plants and a wandering Jew left over by the windows had all turned brown. Occasionally the hot air stirred by a fan swept a dead leaf to the floor.

In this scene of lassitude was a woman who stood apart from the rest. To be more accurate, she sat apart from the rest. Her name was Isabelle Goodrow, and because she was the secretary to Avery Clark, her desk did not face anyone. It faced instead the glassed-in office of Avery Clark himself, his office being an oddly constructed arrangement of wood paneling and large panes of glass (ostensibly to allow him to keep an eye on his workers, though he seldom looked up from his desk), and it was commonly referred to as "the fishbowl." Being the boss's secretary gave Isabelle Goodrow a status different from the other women in the room, but she was different anyway. For example, she was impeccably dressed; even in this heat she wore pantyhose. At a glance she might seem pretty, but if you looked closer you saw that in fact it didn't really get that far, her looks stopped off at plain. Her hair was certainly plain-thin and dark brown, pulled back in a bun or a twist. This hairstyle made her look older than she was, as well as a little school-marmish, and her dark, small eyes held an expression of constant surprise.

While the other women tended to sigh a great deal, or make trips back and forth to the soda machine, complaining of backaches and swollen feet, warning each other against slipping off shoes because you'd never in a hundred years get them back on, Isabelle Goodrow kept fairly still. Isabelle Goodrow simply sat at her desk with her knees together, her shoulders back, and typed away at a steady pace. Her neck was a little peculiar. For a short woman it seemed excessively long, and it rose up from her collar like the neck of the swan seen that summer on the dead-looking river, floating perfectly still by the foamy-edged banks.

Or, at any rate, Isabelle's neck appeared this way to her daughter, Amy, a girl of sixteen that summer, who had taken a recent dislike to the sight of her mother's neck (to the sight of her mother, period), and who anyway had never cared one bit for the swan. In a number of ways Amy did not resemble her mother. If her mother's hair was dull and thin, Amy's hair was a thick, streaky blond. Even cut short the way it was now, haphazardly below her ears, it was noticeably healthy and strong. And Amy was tall. Her hands were large, her feet were long. But her eyes, bigger than her mother's, often held the same expression of tentative surprise, and this startled look could produce some uneasiness in the person on whom her eyes were fixed. Although Amy was shy, and seldom fixed her eyes on anyone for long. She was more apt to glance at people quickly before turning her head. In any event, she didn't know really what kind of impression, if any, she made, even though she had privately in the past studied herself a great deal in any available mirror.

But that summer Amy wasn't looking into any mirrors. She was avoiding them, in fact. She would have liked to avoid her mother as well, but that was impossible-they were working in the office room together. This summer arrangement had been arrived at months before, by her mother and Avery Clark, and while Amy was told to be grateful for the job, she was not. The job was very dull. She was required to add on an adding machine the last column of numbers of each orange invoice that lay on a stack on her desk, and the only good thing was that sometimes it seemed like her mind went to sleep.

The real problem, of course, was that she and her mother were together all day. To Amy it seemed as though a black line connected them, nothing bigger than something drawn with a pencil, perhaps, but a line that was always there. Even if one of them left the room, went to the ladies' room or to the water fountain out in the hall, let's say, it didn't matter to the black line; it simply cut through the wall and connected them still. They did the best they could. At least their desks were far apart and didn't face each other.

Amy sat in a far corner at a desk that faced Fat Bev. This was where Dottie Brown usually sat, but Dottie Brown was home getting over a hysterectomy that summer. Every morning Amy watched as Fat Bev measured out psyllium fiber and shook it vigorously into a pint-sized carton of orange juice. "Lucky you," Fat Bev said. "Young and healthy and all the rest. I bet you never even think about your bowels." Amy, embarrassed, would turn her head.

Fat Bev always lit a cigarette as soon as her orange juice was done. Years later a law would be passed preventing her from doing this in the workplace-at which point she would gain another ten pounds and retire-but right now she was still free to suck in hard and exhale slowly, until she stubbed the cigarette out in the glass ashtray and said to Amy, "That did the trick, got the engine started." She gave Amy a wink as she heaved herself up and hauled her large self off to the bathroom.

It was interesting, really. Amy had not known that cigarettes could make you go to the bathroom. This was not the case when she and Stacy Burrows smoked them in the woods behind the school. And she didn't know that a grown-up woman would talk about her bowels so comfortably. This, in particular, made Amy realize how differently from other people she and her mother lived.

Fat Bev came back from the bathroom, sighing as she sat down, plucking pieces of tiny lint from the front of her huge sleeveless blouse. "So," she said, reaching for the telephone, a half-moon of dampness showing on the pale blue cloth beneath her armpit, "guess I'll give old Dottie a call." Fat Bev called Dottie Brown every morning. She dialed the telephone now with the end of a pencil and cradled the receiver between her shoulder and neck.

"Still bleeding?" she asked, tapping her pink nails against the desk, pink disks almost embedded in flesh. They were Watermelon Pink-she had shown Amy the bottle of polish. "Setting a record or something? Never mind, don't hurry back. No one misses you a bit." Fat Bev picked up an Avon magazine and fanned herself, her chair creaking as she leaned back. "I mean that, Dot. Much nicer to look at Amy Goodrow's sweet face than hear you go on about your cramps." She gave Amy a wink.

Amy looked away, pushing a number on the adding machine. It was a nice thing for Fat Bev to say, but of course it wasn't true. Fat Bev missed Dottie a lot. And why wouldn't she? They had been friends forever, sitting in this room for longer than Amy had been alive, although it boggled Amy's mind to think that. Besides, another thing to consider was how much Fat Bev loved to talk. She said so herself. "I can't shut up for five minutes," she said, and Amy, keeping an eye on the clock one day, had found this to be true. "I need to talk," Fat Bev explained. "It's a kind of physical thing." It seemed she had a point. It seemed her need to talk was as persistent as her need to consume Life Savers and cigarettes, and Amy, who loved Fat Bev, was sorry her own reticence must provide a disappointment. Without forming the thought completely, she blamed her mother for this. Her mother was not a particularly talkative person, either. Look how she just sat there all day typing, never stopping by anyone's desk to ask how they were doing, to complain about the heat. She must know she was considered a snob. Being her daughter, Amy would have to be considered one too.

But Fat Bev didn't seem the least bit disappointed about sharing her corner with Amy. She hung up the telephone and leaned forward, telling Amy in a soft, confiding voice that Dottie Brown's mother-in-law was the most selfish woman in town. Dottie had a hankering for potato salad, which of course was a very good sign, and when she mentioned this to her mother-in-law, who everyone knew happened to make the best potato salad around, Bea Brown suggested that Dottie get up out of bed and go peel some potatoes herself.

"That's awful," Amy offered sincerely.

"I guess it is." Fat Bev sat back and yawned, patting her fleshy throat while her eyes watered. "Honey," she said, nodding, "you marry a man whose mother is dead."

The lunchroom in the factory was a messy, worn-out-looking place. Vending machines lined one wall, a cracked mirror ran the length of another; tables with linoleum chipping from their tops were haphazardly pushed together or apart as the women arranged themselves, spreading out their lunch bags, their soda cans and ashtrays, unwrapping sandwiches from wax paper. Amy positioned herself, as she did every day, away from the cracked mirror.

Isabelle sat at the same table, shaking her head as the story was told of Bea Brown's egregious remark to Dottie. Arlene Tucker said it was probably due to hormones, that if you looked carefully at Bea Brown's chin you'd see she had whiskers, and it was Arlene's belief that women like that were apt to have nasty dispositions. Rosie Tanguay said the trouble with Bea Brown was that she had never worked a day in her life, and the conversations broke into little groups after that, desultory voices overlapping. Quick barks of laughter punctuated one tale, serious tooth-sucking accompanied another.

Amy enjoyed this. Everything talked about was interesting to her, even the story of a refrigerator gone on the blink: a half gallon of chocolate ice cream melted in the sink, soured, and smelled to high hell by morning. The voices were comfortable and comforting; Amy, in her silence, looked from face to face. She was not excluded from any of this, but the women had the decency, or lack of desire, not to try to engage her in their conversations either. It took Amy's mind off things. She would have enjoyed it more, of course, if her mother hadn't been there, but the gentle commotion of the place gave them a certain respite from each other, even with the black line between them continuing to hover.

Fat Bev hit a button on the soda machine and a can of Tab rocked noisily into place. She bent her huge body to retrieve it. "Three more weeks and Dottie can have sex," she said. The black line tightened between Amy and Isabelle. "She wishes it was three more months," and here the soda can was popped open. "But I take it Wally's getting irritable. Chomping at the bit."

Amy swallowed the crust of her sandwich.

"Tell him to take care of it himself," someone said, and there was laughter. Amy's heartbeat quickened, sweat broke out above her lip.

"You get dry after a hysterectomy, you know." Arlene Tucker offered this with a meaningful nod of her head.

"I didn't."

"Because you didn't have your ovaries out." Arlene nodded again-she was a woman who believed what she said. "They yanked the whole business with Dot."

"Oh, my mother went crazy with the hot flashes," somebody said, and thankfully-Amy could feel her heart slow down, her face get cooler in the heat-irritable Wally was left behind; hot flashes and crying jags were talked of instead.

Isabelle wrapped up the remains of her sandwich and returned it to her lunch bag. "It's really too warm to eat," she murmured to Fat Bev, and it was the first time Amy had heard her mother mention the heat.

"Oh, Jesus, that would be nice." Bev chuckled, her big chest ris- ing. "Never too hot for me to eat."

Isabelle smiled and took a lipstick from her purse.

Amy yawned. She was suddenly exhausted; she could have put her head on the table right there and fallen asleep.

"Honey, I'm curious," Fat Bev was saying. She had just lit a cigarette and was gazing through the smoke at Amy. She picked a piece of tobacco from her lip, glancing at it before she flicked it to the floor. "What was it made you decide to cut your hair?"

The black line vibrated and hummed. Without wanting to, Amy looked at her mother. Isabelle was applying lipstick in a hand mirror with her head tilted slightly back; her hand with the lipstick stopped.

"It's cute," Bev added. "Cute as could be. I was just curious, is all. With a head full of hair like yours."

Amy turned her face toward the window, touching the tip of her ear. Women tossed their lunch bags into the trash, brushing crumbs from their fronts, yawning with fists to their mouths as they stood up.

"Probably cooler that way," Fat Bev said.

"It is. Much cooler." Amy looked at Bev and then away.

Fat Bev sighed loudly. "Okay, Isabelle," she said. "Come on. It's back to the salt mines we go."

Isabelle was pressing her lips together, snapping her pocketbook shut. "That's right," she said, not looking at Amy. "There's no rest for the weary, you know."

But Isabelle had her story. And years before when she had first shown up in town, renting the old Crane house out on Route 22, installing her few possessions and infant daughter (a serious-looking child with a head of pale, curly hair), there had been some curiosity among the members of the Congregational church, and among the women she joined in the office room at the mill as well.

But the young Isabelle Goodrow had not been forthcoming. She answered simply that her husband was dead, as well as her parents, and that she had moved down the river to Shirley Falls to have a better chance at earning a living. Really, nobody knew much more. Although a few people noticed that when she had first arrived in town she wore her wedding ring, and that after a while she didn't wear it anymore.

She did not seem to make friends. She did not make enemies either, although she was a conscientious worker and as a result went through a series of promotions. Each time there was some grumbling in the office room, this last time in particular, when she had risen well above the others by becoming the personal secretary to Avery Clark, but no one wished her any ill. There were jokes, remarks, made behind her back at times, about how she needed a good roll in the hay to loosen her up, but that kind of thing lessened as the years went by. At this point she was an old-timer. Amy's fear that her mother was seen as a snob was not particularly warranted. It was true the women gossiped about one another, but Amy was too young to understand that the kind of familial acceptance they had for each other extended to her mother as well.

Still, no one would claim to know Isabelle. And certainly no one guessed the poor woman right now was going through hell. If she seemed thinner than usual, a little more pale, well, it was dreadfully hot. So hot that even now, at the end of the day, the heat rose up from the tar as Amy and Isabelle walked across the parking lot.

"Have a good evening, you two," Fat Bev called out, as she hoisted herself into her car.

Read more

About the authors

Elizabeth Strout

Elizabeth Strout is the author of the New York Times bestseller Olive Kitteridge, for which she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize; the national bestseller Abide with Me; and Amy and Isabelle, winner of the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award and the Chicago Tribune Heartland Prize. She has also been a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award and the Orange Prize in London. She lives in Maine and New York City.

Read more

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.3 out of 5

9,403 global ratings

K. N. Grieshaber

5

Human nature Captured in written form

Reviewed in the United States on December 17, 2021

Verified Purchase

Wow! This is a fabulous and painful story about a single mother raising a teenager. Both Isabelle and Amy are strong characters, and because the book was written in 1998, its not about today's teenagers, but it is a universally relevant story. There were many incredible moments in this very well told story. My only complaint was that Stacy, an unwed teenaged girl who is Amy's smoking buddy, never discusses sex with the innocent Amy. The fact that these two are close and at that age seems unlikely that they wouldn't talk about sex in their discussions. There are many things to love: the factory women, the new teacher( well...), the painful self- consciousness of Amy and the inadequacy that Isabelle feels around the preacher's snobby wife. All in all the unfolding of the story is genius, and its almost curious why it's not considered a classic must-read. Having discovered Elizabeth Strout late, I'm going to make an effort to read other works by her. As a writer she is truly outstanding.

Read more

HT

5

A detailed, beautiful examination of how a moment of change can push lives into new paths.

Reviewed in the United States on October 24, 2014

Verified Purchase

Like The Burgess Boys, Amy and Isabelle is a powerful story about how a moment can spin lives into new paths. Reflecting back Isabelle ponders "She had never really imagined-that was the thing. But imagine it now, standing in your kitchen, wondering what to make for dinner that night, checking the refrigerator-and the telephone rings. One minute your world is one way, the next minute it's all caved in." (Loc 4889)

There are a few such moments in the novel. Toward the end viewing a friend's moment of crisis "...she [Isabelle] could see. She could easily see that. God knew she could see how one's entire life could be taken apart and that Dottie's life was being taken apart right now, almost in front of Isabelle's eyes." (Loc 4061).

Unlike The Burgess Boys where we see the impact an accident affects the lives of siblings half a lifetime later, in Amy And Isabelle we see the primary moment of change, Amy's seduction by her teacher, build slowly but inexorably through the first half of the book. Powerful and destructive changes occur immediately and affect the mother and daughter the rest of their lives. Isabelle's struggle is to find some sense of grace and forgiveness both for her daughter and herself.

Then tension builds again for another set of changes one night that adjusts the course of lives once again. "But what could you do? Only keep going. People kept going; they had been doing it for thousands of years. You took the kindness offered, letting it seep as far in as it could go, and the remaining dark crevices you carried around with you, knowing that over time they might change into something almost bearable. Dottie, Bev, Isabelle, in their own ways knew this. But Amy was young. She didn't know yet what se could or could not bear, and silently she clung like a dazed child to all three mothers in the room." (Loc 4993)

Elizabeth Strout is a wonderful writer. She comfortably and completely inhabits her characters and their physical and emotional landscapes. She has a beautiful style of writing and weaves words together to build a work of art. I particularly like one aspect of her style where she doesn't show us the internal view of one of the major characters - Mr Robertson the teacher in this case. We only see him through the eyes of Amy and Isabelle; so we never get a sense of his motivations and struggles.

Strout does a marvelous job examining one small moment are viewed so differently by the different people involved: "'Are you hungry, Amy? Would you like something to eat?' And Amy simply shook her head, not able to speak because of some swift, unarticulated compassion for her mother. But Isabelle in her memory, for the rest of her life, saw Amy's indifferent shake of her head as proof that already the girl had been lost to her..." (Loc 5292).

Elizabeth Strout captures these universal moments we all experience and reflects them back to us clearly and powerfully; isn't that the job of an artist?

Read more

20 people found this helpful

jan wallace

5

Ordinary people living ordinary lives

Reviewed in the United States on April 2, 2024

Verified Purchase

I loved the writing, the characters and the beautiful, poignant story. It was hard to put down. I love all her books.

Top Elizabeth Strout titles

View all

The Burgess Boys: A Novel

4.1

-

11,063

$2.11

Oh William!: A Novel

4.2

-

22,498

$5.04

Lucy by the Sea: A Novel

4.3

-

18,461

$4.00

Anything Is Possible: A Novel

4

-

19,323

$5.35

Olive, Again: A Novel (Olive, 2)

4.4

-

24,861

$9.76

My Name Is Lucy Barton: A Novel

3.8

-

36,168

$7.94

Olive Kitteridge

4.2

-

30,647

$9.49

Tell Me Everything: Oprah's Book Club: A Novel

4.5

-

2,665

$14.99

Similar Books

Best sellers

View all

The Tuscan Child

4.2

-

100,022

$8.39

The Thursday Murder Club: A Novel (A Thursday Murder Club Mystery)

4.3

-

155,575

$6.33

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

4.6

-

140,302

$13.49

The Butterfly Garden (The Collector, 1)

4.3

-

88,556

$9.59

Things We Hide from the Light (Knockemout Series, 2)

4.4

-

94,890

$11.66

The Last Thing He Told Me: A Novel

4.3

-

154,085

$2.99

The Perfect Marriage: A Completely Gripping Psychological Suspense

4.3

-

143,196

$9.47

The Coworker

4.1

-

80,003

$13.48

First Lie Wins: A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.3

-

54,062

$14.99

Mile High (Windy City Series Book 1)

4.4

-

59,745

$16.19

Layla

4.2

-

107,613

$8.99

The Locked Door

4.4

-

94,673

$8.53