The Nightingale: A NovelAudiobook

4.7

-

309,637 ratings

A #1 New York Times bestseller, Wall Street Journal Best Book of the Year, and soon to be a major motion picture, this unforgettable novel of love and strength in the face of war has enthralled a generation.

France, 1939 - In the quiet village of Carriveau, Vianne Mauriac says goodbye to her husband, Antoine, as he heads for the Front. She doesn't believe that the Nazis will invade France … but invade they do, in droves of marching soldiers, in caravans of trucks and tanks, in planes that fill the skies and drop bombs upon the innocent. When a German captain requisitions Vianne's home, she and her daughter must live with the enemy or lose everything. Without food or money or hope, as danger escalates all around them, she is forced to make one impossible choice after another to keep her family alive.

Vianne's sister, Isabelle, is a rebellious eighteen-year-old girl, searching for purpose with all the reckless passion of youth. While thousands of Parisians march into the unknown terrors of war, she meets Gäetan, a partisan who believes the French can fight the Nazis from within France, and she falls in love as only the young can … completely. But when he betrays her, Isabelle joins the Resistance and never looks back, risking her life time and again to save others.

With courage, grace, and powerful insight, bestselling author Kristin Hannah captures the epic panorama of World War II and illuminates an intimate part of history seldom seen: the women's war. The Nightingale tells the stories of two sisters, separated by years and experience, by ideals, passion and circumstance, each embarking on her own dangerous path toward survival, love, and freedom in German-occupied, war-torn France―a heartbreakingly beautiful novel that celebrates the resilience of the human spirit and the durability of women. It is a novel for everyone, a novel for a lifetime.

Goodreads Best Historical Novel of the Year • People's Choice Favorite Fiction Winner • #1 Indie Next Selection • A Buzzfeed and The Week Best Book of the Year

Praise for The Nightingale:

"Haunting, action-packed, and compelling." ―Christina Baker Kline, #1 New York Times bestselling author

"Absolutely riveting!...Read this book." ―Dr. Miriam Klein Kassenoff, Director of the University of Miami Holocaust Teacher Institute

"Beautifully written and richly evocative." ―Sara Gruen, #1 New York Times bestselling author

“A hauntingly rich WWII novel about courage, brutality, love, survival―and the essence of what makes us human.” --Family Circle

“A heart-pounding story.” ―USA Today

"An enormous story. Richly satisfying. loved it," ―Anne Rice

"A respectful and absorbing page-turner." ―Kirkus Reviews

"Tender, compelling...a satisfying slice of life in Nazi-occupied France." ―Jewish Book Council

“Expect to devour The Nightingale in as few sittings as possible; the high-stakes plot and lovable characters won’t allow any rest until all of their fates are known.” ―Shelf Awareness

"I loved The Nightingale." ―Lisa See, #1 New York Times bestselling author

"Powerful...an unforgettable portrait of love and war." ―People

Read more

Kindle

$11.99

Available instantly

Audiobook

$0.00

with membership trial

Hardcover

$31.50

Paperback

$9.40

Ships from

Amazon.com

Payment

Secure transaction

ISBN-10

1250080401

ISBN-13

978-1250080400

Print length

608 pages

Language

English

Publisher

St. Martin's Griffin

Publication date

April 24, 2017

Dimensions

5.5 x 1.55 x 8.15 inches

Item weight

1.21 pounds

Popular highlights in this book

I always thought it was what I wanted: to be loved and admired. Now I think perhaps I’d like to be known.

Highlighted by 23,768 Kindle readers

“But love has to be stronger than hate, or there is no future for us.”

Highlighted by 14,393 Kindle readers

“Don’t think about who they are. Think about who you are and what sacrifices you can live with and what will break you.”

Highlighted by 12,757 Kindle readers

Product details

ASIN :

B00JO8PEN2

File size :

8218 KB

Text-to-speech :

Enabled

Screen reader :

Supported

Enhanced typesetting :

Enabled

X-Ray :

Enabled

Word wise :

Enabled

Editorial reviews

Praise for The Nightingale:

"Haunting, action-packed, and compelling." ―Christina Baker Kline, #1 New York Times bestselling author

"Absolutely riveting!...Read this book." ―Dr. Miriam Klein Kassenoff, Director of the University of Miami Holocaust Teacher Institute

"Beautifully written and richly evocative." ―Sara Gruen, #1 New York Times bestselling author

“A hauntingly rich WWII novel about courage, brutality, love, survival―and the essence of what makes us human.” ―Family Circle

“A heart-pounding story.” ―USA Today

"An enormous story. Richly satisfying. I loved it." ―Anne Rice

"A respectful and absorbing page-turner." ―Kirkus Reviews

"Tender, compelling...a satisfying slice of life in Nazi-occupied France." ―Jewish Book Council

“Expect to devour The Nightingale in as few sittings as possible; the high-stakes plot and lovable characters won’t allow any rest until all of their fates are known.” ―Shelf Awareness

"I loved The Nightingale." ―Lisa See, #1 New York Times bestselling author

"Powerful...an unforgettable portrait of love and war." ―People

Sample

ONE

April 9, 1995

The Oregon Coast

If I have learned anything in this long life of mine, it is this: In love we find out who we want to be; in war we find out who we are. Today’s young people want to know everything about everyone. They think talking about a problem will solve it. I come from a quieter generation. We understand the value of forgetting, the lure of reinvention.

Lately, though, I find myself thinking about the war and my past, about the people I lost.

Lost.

It makes it sound as if I misplaced my loved ones; perhaps I left them where they don’t belong and then turned away, too confused to retrace my steps.

They are not lost. Nor are they in a better place. They are gone. As I approach the end of my years, I know that grief, like regret, settles into our DNA and remains forever a part of us.

I have aged in the months since my husband’s death and my diagnosis. My skin has the crinkled appearance of wax paper that someone has tried to flatten and reuse. My eyes fail me often—in the darkness, when headlights flash, when rain falls. It is unnerving, this new unreliability in my vision. Perhaps that’s why I find myself looking backward. The past has a clarity I can no longer see in the present.

I want to imagine there will be peace when I am gone, that I will see all of the people I have loved and lost. At least that I will be forgiven.

I know better, though, don’t I?

My house, named The Peaks by the lumber baron who built it more than a hundred years ago, is for sale, and I am preparing to move because my son thinks I should.

He is trying to take care of me, to show how much he loves me in this most difficult of times, and so I put up with his controlling ways. What do I care where I die? That is the point, really. It no longer matters where I live. I am boxing up the Oregon beachside life I settled into nearly fifty years ago. There is not much I want to take with me. But there is one thing.

I reach for the hanging handle that controls the attic steps. The stairs unfold from the ceiling like a gentleman extending his hand.

The flimsy stairs wobble beneath my feet as I climb into the attic, which smells of must and mold. A single, hanging lightbulb swings overhead. I pull the cord.

It is like being in the hold of an old steamship. Wide wooden planks panel the walls; cobwebs turn the creases silver and hang in skeins from the indentations between the planks. The ceiling is so steeply pitched that I can stand upright only in the center of the room.

I see the rocking chair I used when my grandchildren were young, then an old crib and a ratty-looking rocking horse set on rusty springs, and the chair my daughter was refinishing when she got sick. Boxes are tucked along the wall, marked “Xmas,” “Thanksgiving,” “Easter,” “Halloween,” “Serveware,” “Sports.” In those boxes are the things I don’t use much anymore but can’t bear to part with. For me, admitting that I won’t decorate a tree for Christmas is giving up, and I’ve never been good at letting go. Tucked in the corner is what I am looking for: an ancient steamer trunk covered in travel stickers.

With effort, I drag the heavy trunk to the center of the attic, directly beneath the hanging light. I kneel beside it, but the pain in my knees is piercing, so I slide onto my backside.

For the first time in thirty years, I lift the trunk’s lid. The top tray is full of baby memorabilia. Tiny shoes, ceramic hand molds, crayon drawings populated by stick figures and smiling suns, report cards, dance recital pictures.

I lift the tray from the trunk and set it aside.

The mementos in the bottom of the trunk are in a messy pile: several faded leather-bound journals; a packet of aged postcards tied together with a blue satin ribbon; a cardboard box bent in one corner; a set of slim books of poetry by Julien Rossignol; and a shoebox that holds hundreds of black-and-white photographs.

On top is a yellowed, faded piece of paper.

My hands are shaking as I pick it up. It is a carte d’identité, an identity card, from the war. I see the small, passport-sized photo of a young woman. Juliette Gervaise.

“Mom?”

I hear my son on the creaking wooden steps, footsteps that match my heartbeats. Has he called out to me before?

“Mom? You shouldn’t be up here. Shit. The steps are unsteady.” He comes to stand beside me. “One fall and—“

I touch his pant leg, shake my head softly. I can’t look up. “Don’t” is all I can say.

He kneels, then sits. I can smell his aftershave, something subtle and spicy, and also a hint of smoke. He has sneaked a cigarette outside, a habit he gave up decades ago and took up again at my recent diagnosis. There is no reason to voice my disapproval: He is a doctor. He knows better.

My instinct is to toss the card into the trunk and slam the lid down, hiding it again. It’s what I have done all my life.

Now I am dying. Not quickly, perhaps, but not slowly, either, and I feel compelled to look back on my life.

“Mom, you’re crying.”

“Am I?”

I want to tell him the truth, but I can’t. It embarrasses and shames me, this failure. At my age, I should not be afraid of anything—certainly not my own past.

I say only, “I want to take this trunk.”

“It’s too big. I’ll repack the things you want into a smaller box.”

I smile at his attempt to control me. “I love you and I am sick again. For these reasons, I have let you push me around, but I am not dead yet. I want this trunk with me.”

“What can you possibly need in it? It’s just our artwork and other junk.”

If I had told him the truth long ago, or had danced and drunk and sung more, maybe he would have seen me instead of a dependable, ordinary mother. He loves a version of me that is incomplete. I always thought it was what I wanted: to be loved and admired. Now I think perhaps I’d like to be known.

��“Think of this as my last request.”

I can see that he wants to tell me not to talk that way, but he’s afraid his voice will catch. He clears his throat. “You’ve beaten it twice before. You’ll beat it again.”

We both know this isn’t true. I am unsteady and weak. I can neither sleep nor eat without the help of medical science. “Of course I will.”

“I just want to keep you safe.”

I smile. Americans can be so naïve.

Once I shared his optimism. I thought the world was safe. But that was a long time ago.

“Who is Juliette Gervaise?” Julien says and it shocks me a little to hear that name from him.

I close my eyes and in the darkness that smells of mildew and bygone lives, my mind casts back, a line thrown across years and continents. Against my will—or maybe in tandem with it, who knows anymore?—I remember.

Read more

About the authors

Kristin Hannah

Kristin Hannah is the award-winning and bestselling author of more than 20 novels. Her newest novel, The Women, about the nurses who served in the Vietnam war, will be released on February 6, 2024.

The Four Winds was published in February of 2021 and immediately hit #1 on the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Indie bookstore's bestseller lists. Additionally, it was selected as a book club pick by the both Today Show and The Book Of the Month club, which named it the best book of 2021.

In 2018, The Great Alone became an instant New York Times #1 bestseller and was named the Best Historical Novel of the Year by Goodreads.

In 2015, The Nightingale became an international blockbuster and was Goodreads Best Historical fiction novel for 2015 and won the coveted People's Choice award for best fiction in the same year. It was named a Best Book of the Year by Amazon, iTunes, Buzzfeed, the Wall Street Journal, Paste, and The Week.

The Nightingale is currently in pre-production at Tri Star. Firefly Lane, her beloved novel about two best friends, was the #1 Netflix series around the world, in the week it came out. The popular tv show stars Katherine Heigl and Sarah Chalke.

A former attorney, Kristin lives in the Pacific Northwest.

Read more

Reviews

Customer reviews

4.7 out of 5

309,637 global ratings

Denise

5

another tale of strength about women's resilience during historical turmoil

Reviewed in the United States on April 1, 2024

Verified Purchase

As I sit down to write this, there's this odd feeling of emptiness and dryness pervading my thoughts. I once stumbled upon this idea that a good review should capture how a book makes you feel, and let me tell you, this one has stirred up so many emotions in me that I hardly know where to start. If I had to sum it up in just one word, I'd probably go with "beautiful" – simple yet profound.

My usual go-to genre is thrillers and mysteries, but there's something about historical novels that always gets me. Especially those set against the backdrop of Asian cultures or the turmoil of World Wars I and II. The way authors, especially women like Kate Quinn, Kristin Hannah, and Min Jin Lee, delicately yet powerfully depict the horrors of war and the human spirit within it – it's absolutely mesmerizing.

War has always felt like a distant concept to me. I come from a country untouched by its scars, and none of my relatives have ever lived through it either. And honestly, I'm grateful for that. But maybe it's this distance that makes me so drawn to reading about it, even through fiction. These stories give me a glimpse into lives lived amidst unimaginable pain and suffering. And while I know nothing can truly capture the horrors of war, I can't help but relate to the everyday struggles faced by those who lived through it. It's both humbling and inspiring to see the strength and resilience of the women who navigated these turbulent times, not just for themselves but for those they loved.

In the words of Kristin Hannah herself, ""Men tell stories," I say. It is the truest, simplest answer to his question. “Women get on with it. For us, it was a shadow war. There were no parades for us when it was over, no medals or mentions in history books. We did what we had to during the war, and when it was over, we picked up the pieces and started our lives over.""

Read more

8 people found this helpful

Lorrie

5

Well researched, well written but be prepared a read that will change you.

Reviewed in the United States on May 19, 2024

Verified Purchase

I love reading WWII books, but this one was one I'll not forget. I felt such an overwhelming heaviness of sadness, it spilled out into my day. I don't know how so many survived. At times, I had to put the book down and take a break. There is no break in the turmoil, torture, and starvation for the jews and for the people of France. Broke my heart. It was a lot, all at once and some of it made me think....how could anyone be that cruel?

I know the author did a ton of research, it shows. I kept hoping for one ounce of happiness or hope and there was none. At first it made me put the book down, but then I thought . . . these people had no break either. Would I read this book again? No. It was just too much for me but a story that many should read. If nothing else, so history does not repeat itself.

Read more

6 people found this helpful

Michelle K

5

Wow!

Reviewed in the United States on June 4, 2024

Verified Purchase

Wow... Just wow... I put off reading this book and any Kristin Hannah book for so long. Now that I have, I am so glad that I did, and I can't wait to read my next. This book was so powerful. The writing was incredible. This book made me feel angry, and sad, and even though I cried (boy did I cry) the way this book ended made my heart smile a little.

If you haven't read this, do it. It will break your heart, but open both it and your eyes to another view of life in WW2. Beautifully written, probably going to be one of my top reads this year.

Read more

2 people found this helpful

Top Kristin Hannah titles

View all

Angel Falls: A Novel

4.3

-

19,320

$2.25

Between Sisters: A Novel (Random House Reader's Circle)

4.5

-

30,096

$8.89

True Colors: A Novel

4.5

-

25,235

$2.14

Distant Shores: A Novel

4.3

-

17,870

$8.72

Firefly Lane: A Novel

4.6

-

49,632

$9.06

Magic Hour: A Novel

4.6

-

33,187

$8.99

Summer Island: A Novel

4.4

-

28,592

$8.94

Night Road

4.5

-

37,965

$10.83

The Great Alone: A Novel

4.6

-

152,447

$5.49

Home Front: A Novel

4.6

-

38,454

$8.00

The Four Winds

4.6

-

156,242

$9.99

Winter Garden

4.6

-

72,838

$7.37

Best sellers

View all

The Tuscan Child

4.2

-

100,022

$8.39

The Thursday Murder Club: A Novel (A Thursday Murder Club Mystery)

4.3

-

155,575

$6.33

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

4.6

-

140,302

$13.49

The Butterfly Garden (The Collector, 1)

4.3

-

88,556

$9.59

Things We Hide from the Light (Knockemout Series, 2)

4.4

-

94,890

$11.66

The Last Thing He Told Me: A Novel

4.3

-

154,085

$2.99

The Perfect Marriage: A Completely Gripping Psychological Suspense

4.3

-

143,196

$9.47

The Coworker

4.1

-

80,003

$13.48

First Lie Wins: A Novel (Random House Large Print)

4.3

-

54,062

$14.99

Mile High (Windy City Series Book 1)

4.4

-

59,745

$16.19

Layla

4.2

-

107,613

$8.99

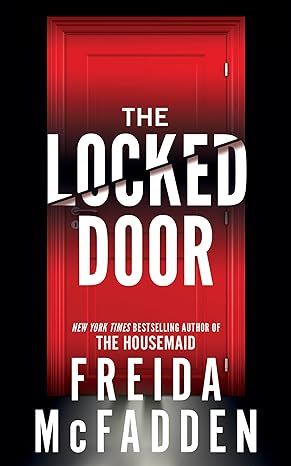

The Locked Door

4.4

-

94,673

$8.53